|

|

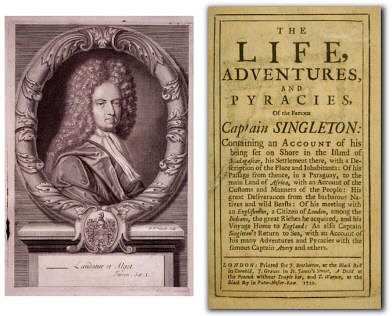

Captain Singleton by Daniel Defoe The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (1720) Defoe was fifty-nine when he published this book, in 1720, the year after 'Robinson Crusoe'. It may have been inspired by the exploits of the English pirate Henry Every. Abridged: JH For more works by Daniel Defoe, see The Index I. - Sailing With the Devil If I may believe the woman whom I was taught to call mother, I was a little boy about two years old, very well dressed, and had a nurse-maid to attend me, who took me out on a fine summer's evening into the fields towards Islington, to give the child some air; a little girl being with her, of twelve or fourteen years old, that lived in the neighbourhood. The maid meets with a fellow, her sweetheart; he carries her into a public-house, and while they are toying in there the girl plays about with me in her hand, sometimes in sight, sometimes out of sight, thinking no harm. Then comes by one of those sort of people who make it their business to spirit away little children, a trade chiefly practised where they found little children well dressed, and for bigger children, to sell them to the plantations. The woman, pretending to take me up in her arms and play with me, draws the girl a good way from the house, and then bids her go back to the maid, and tell her that a gentlewoman had taken a fancy to the child. And so, while the girl went, she carries me quite away. From that time, it seems, I was disposed of to a beggar woman, and after that to a gipsy, till I was about six years old. And this gipsy, though I was continually dragged about with her from one part of the country to the other, never let me want for anything. I called her mother, but she told me at last she was not my mother, but that she bought me for twelve shillings, and that my name was Bob Singleton, not Robert, but plain Bob. Who my father and mother really were I have never learnt. When my gipsy mother happened in process of time to be hanged, I was sent to a parish school; and then I was moved from one parish to another, and at Bussleton, near Southampton, the master of a ship took a fancy to me, and though I was not above twelve years old, he carried me to sea with him on a voyage to Newfoundland. I went several voyages with him, when, coming home from Newfoundland about the year 1695, we were taken by an Algerine rover, which was in its turn taken by two great Portuguese men-of-war. We were carried into Lisbon, and there my master, the only friend I had in the world, dying of his wounds, I was left starving in a foreign country where I knew nobody, and could not speak a word of the language. However, an old pilot found me, and, speaking in broken English, asked me if I would go with him. "Yes," said I, "with all my heart." For two years I lived with him, and then he got to be master under Don Garcia de Carravallas, captain of a Portuguese galleon, which was bound to Goa in the East Indies. On this voyage I began to get a smattering of the Portuguese tongue and a superficial knowledge of navigation. I also learnt to be an arrant thief and a bad sailor. I was reputed as mighty diligent and faithful to my master, but I was very far from honest. Indeed, I had no sense of virtue or religion in me, never having heard much of either, and was growing up apace to be as wicked as anybody could be. Thieving, lying, swearing, forswearing, joined to the most abominable lewdness, was the stated practice of the ship's crew; adding to it that, with the most insufferable boasts of their own courage, they were, generally speaking, the most complete cowards that I ever met with. And I was exactly fitted for their society. According to the English proverb, he that is shipped with the devil must sail with the devil; I was among them, and I managed myself as well as I could. When we came to anchor on the coast of Madagascar to repair some damage to the ship, there happened a most desperate mutiny among the men upon account of a deficiency in their allowance, and I, being full of mischief in my head, readily joined. Though I was but a boy, as they called me, yet I prompted the mischief all I could, and embarked in it so openly that I escaped very little being hanged in the first and most early part of my life. For the captain, getting wind of the plot, brought two fellows to confess the particulars, and presently no less than sixteen men were seized and put into irons, whereof I was one. The captain, who was made desperate by his danger, tried us all, and we were all condemned to die. The gunner and purser were hanged immediately, and I expected it with the rest. I do not remember any great concern I was under about it, only that I cried very much; for I knew little then of this world, and nothing at all of the next. However, the captain contented himself with executing these two, and some of the rest, upon their humble submission, were pardoned; but five were ordered to be set on shore on the island and left there, of which I was one. At our first coming into the island we were terrified exceedingly with the sight of the barbarous people; but when we came to converse with them awhile, we found they were not cannibals, as was reported, but they came and sat down by us, and wondered much at our clothes and arms. Nor did we suffer any harm from them during our whole stay on the island. Before the ship sailed twenty-three of the crew decided to join us, and the captain, not unwilling to lose them, sent us two barrels of powder, and shot and lead, as well as a great bag of bread. Being now a considerable number, and in condition to defend ourselves, the first thing we did was to give everyone his hand that we would not separate from one another, but that we would live and die together, that we would be in all things guided by the majority, that we would appoint a captain among us to be our leader, and that we would obey him on pain of death. II. - A Mad Venture For two years we remained on the island of Madagascar, for at the beginning we had no vessel large enough to pass the ocean. I never proposed to speak in the general consultations, but one day I told the company that our best plan was to cruise along the coast in canoes, and seize upon the first vessel we could get that was better than our own, and so from that to another, till perhaps we might at last get a good ship to carry us wherever we pleased to go. "Excellent advice," says one of them. "Admirable advice," says another. "Yes, yes," says the third (which was a gunner), "the English dog has given excellent advice, but it is just the way to bring us all to the gallows. To go a-thieving, till from a little vessel we come to a great ship, and so shall we turn downright pirates, the end of which is to be hanged." "You may call us pirates," says another, "if you will, and if we fall into bad hands we may be used like pirates; but I care not for that. I'll be a pirate or anything, rather than starve here!" And so they cried all, "Let us have a canoe!" The gunner, overruled by the rest, submitted; but as we broke up the council, he came to me and very gravely. "My lad," says he, "thou art born to do a world of mischief; thou hast commenced pirate very young; but have a care of the gallows, young man; have a care, I say, for thou wilt be an eminent thief." I laughed at him, and told him I did not know what I might come to hereafter; but as our case was now, I should make no scruple to take the first ship I came at to get our liberty. I only wished we could see one, and come at her. When we had made three canoes of some size, we set out on as odd a voyage as ever man went. We were a little fleet of three ships, and an army of between twenty and thirty as dangerous fellows as ever lived. We were bound somewhere and nowhere, for though we knew what we intended to do, we really did not know what we were doing. We cruised up and down the coast, but no ship came in sight, and at last, with more courage than discretion, more resolution than judgment, we launched for the main coast of Africa. The voyage was much longer than we expected, and when we were landed upon the continent it seemed the most desolate, desert, and inhospitable country in the world. It was here that we took one of the rashest and wildest and most desperate resolutions that ever was taken by man; this was to travel overland through the heart of the country, from the coast of Mozambique to the coast of Angola or Guinea, a continent of land of at least 1,800 miles, in which journey we had excessive heats to support, impassable deserts to go over, no carriages, camels, or beasts of any kind to carry our baggage, innumerable wild and ravenous beasts to encounter, such as lions, leopards, tigers, lizards, and elephants; we had nations of savages to encounter, barbarous and brutish to the last degree; hunger and thirst to struggle with, and, in one word, terrors enough to have daunted the stoutest hearts that ever were placed in cases of flesh and blood. Yet, fearless of all these, we resolved to adventure, and not only did we accomplish our journey, but we came to a river where there were vast quantities of gold. The hardships and difficulties of our march were much mitigated by a method which I proposed and was found very convenient. This was to quarrel with some of the negro natives, take them as prisoners, and binding them, as slaves, cause them to travel with us and make them carry our baggage. Accordingly, we secured about sixty lusty young fellows as prisoners, for the natives stood in great awe of us because of our firearms, and they not only served us faithfully - the more so as we treated them without harshness - but were of great help in showing us the way, and in conversing with the savages we afterwards met. When we reached the country where the gold was, we at once agreed, in order that the good harmony and friendship of our company might be maintained, that however much gold was gotten, it should be brought into one common stock, and equally divided at last, the negroes sharing with the rest. This was done, and at the end of our long journey we found each man's share amounted to many pounds of gold. We also got a cargo of elephants' teeth. We parted at the Gold Coast from our black companions on the best of terms. Then most of my comrades went off to the Portuguese factories near Gambia, and I went to Cape Coast Castle, and got passage for, England, where I arrived in September. III. - Quaker and Pirate I had neither friend nor relation in England, though it was my native country; I had not a person to trust with what I had, or to counsel me to secure or save it; but falling into ill company, and trusting the keeper of a public-house in Rotherhithe with a great part of my money, all that great sum, which I got with so much pains and hazard, was gone in little more than two years' time - spent in all kinds of folly and wickedness. Then I began to see it was time to think of further adventures, and I next shipped myself, in an evil hour to be sure, on a voyage to Cadiz. On the coast of Spain I fell in with some masters of mischief, and, among them, one, forwarder than the rest, named Harris, who began an intimate confidence with me, so that we called one another brothers. This Harris was afterwards captured by an English man-of-war, and, being laid in irons, died of grief and anger. When we were together, he asked me if I had a mind for an adventure that might make amends for all past misfortunes. I told him, yes, with all my heart; for I did not care where I went, having nothing to lose, and no one to leave behind me. He told me, then, there was a brave fellow, whose name was Wilmot, in another English ship which rode in the harbour, who had resolved to mutiny the next morning, and run away with the ship; and that if we could get strength enough among our ship's company, we might do the same. I liked the proposal very well, but we could not bring our part to perfection. For there were but eleven in our ship who were in the conspiracy, nor could we get any more that we could trust. So that when Wilmot began his work, and secured the ship, and gave the signal to us, we all took a boat and went off to join him. Being well prepared for all manner of roguery, without the least checks of conscience, I thus embarked with this crew, which at last brought me to consort with the most famous pirates of the age. I, that was an original thief, and a pirate even by inclination before, was now in my element, and never undertook anything in my life with more particular satisfaction. Captain Wilmot - for so we now called him - at once stood out for sea, steering for the Canaries, and thence onward to the West Indies. Our ship had twenty-two guns, and we obtained plenty of ammunition from the Spaniards in exchange for bales of English cloth. We cruised near two years in those seas of the West Indies, chiefly upon the Spaniards - not that we made any difficulty of taking English ships, or Dutch, or French, if they came in our way. But the reason why we meddled as little with English vessels as we could was, first, because if they were ships of any force, we were sure of more resistance from them; and, secondly, because we found the English ships had less booty when taken; for the Spaniards generally had money on board, and that was what we best knew what to do with. We increased our stock considerably in these two years, having taken 60,000 pieces of gold in one vessel, and 100,000 in another; and being thus first grown rich, we resolved to be strong, too, for we had taken a brigantine, an excellent sea-boat, able to carry twelve guns, and a large Spanish frigate-built ship, which afterwards, by the help of good carpenters, we fitted up to carry twenty-eight guns. We had also taken two or three sloops from New England and New York, laden with flour, peas, and barrelled beef and pork, going for Jamaica and Barbados, and for more beef we went on shore on the island of Cuba, where we killed as many black cattle as we pleased, though we had very little salt to cure them. Out of all the prizes we took here we took their powder and bullets, their small-arms and cutlasses; and as for their men, we always took the surgeon and the carpenter, as persons who were of particular use to us upon many occasions; nor were they always unwilling to go with us. We had one very merry fellow here, a Quaker, whose name was William Walters, whom we took out of a sloop bound from Pennsylvania to Barbados. He was a surgeon and they called him doctor, and we made him go with us, and take all his implements with him. He was a comic fellow indeed, a man of very good solid sense, and an excellent surgeon; but, what was worth all, very good-humoured and pleasant in his conversation, and a bold, stout, brave fellow too, as any we had among us. I found William not very averse to go along with us, and yet resolved to do it so that it might be apparent he was taken away by force. "Friend," he says, "thou sayest I must go with thee, and it is not in my power to resist thee if I would; but I desire thou wilt oblige the master of the sloop to certify under his hand that I was taken away by force, and against my will." So I drew up a certificate myself, wherein I wrote that he was taken away by main force, as a prisoner, by a pirate ship; and this was signed by the master and all his men. "Thou hast dealt friendly by me," says he, when we had brought him aboard, "and I will be plain with thee, whether I came willingly to thee or not. But thou knowest it is not my business to meddle when thou art to fight." "No, no," says the captain, "but you may meddle a little when we share the money." "Those things are useful to furnish a surgeon's chest," says William, and smiled, "but I shall be moderate." In short, William was a most agreeable companion; but he had the better of us in this part, that if we were taken we were sure to be hanged, and he was sure to escape. But he was a sprightly fellow, and fitter to be captain than any of us. IV. - A Respectable Merchant We cruised the seas for many years, and after a time William and I had a ship to ourselves with 400 men in authority under us. As for Captain Wilmot, we left him with a large company at Madagascar, while we went on to the East Indies. At last we had gotten so rich, for we traded in cloves and spices to the merchants, that William one day proposed to me that we should give up the kind of life we had been leading. We were then off the coast of Persia. "Most people," said William, "leave off trading when they are satisfied of getting, and are rich enough; for nobody trades for the sake of trading; much less do men rob for the sake of thieving. It is natural for men that are abroad to desire to come home again at last, especially when they are grown rich, and so rich as they would know not what to do with more if they had it." "Well, William," said I, "but you have not explained what you mean by home. Why, man, I am at home; here is my habitation; I never had any other in my lifetime; I was a kind of charity school-boy; so that I can have no desire of going anywhere for being rich or poor; for I have nowhere to go." "Why," says William, looking a little confused, "hast thou no relatives or friends in England? No acquaintance; none that thou hast any kindness or any remains of respect for?" "Not I, William," said I, "no more than I have in the court of the Great Mogul. Yet I do not say I like this roving, cruising life so well as never to give it over. Say anything to me, I will take it kindly." For I could see he was troubled, and I began to be moved by his gravity. "There is something to be thought of beyond this way of life," says William. "Why, what is that," said I, "except it be death?" "It is repentance." "Why," says I, "did you ever know a pirate repent?" At this he was startled a little, and returned. "At the gallows I have known one, and I hope thou wilt be the second." He spoke this very affectionately, with an appearance of concern for me. "My proposal," William went on, "is for thy good as well as my own. We may put an end to this kind of life, and repent." "Look you, William," says I, "let me have your proposal for putting an end to our present way of living first, and you and I will talk of the other afterwards." "Nay," says William, "thou art in the right there; we must never talk of repenting while we continue pirates." "Well," says I, "William, that's what I meant; for if we must not reform, as well as be sorry for what is done, I have no notion what repentance means: the nature of the thing seems to tell me that the first step we have to take is to break off this wretched course. Dost thou think it practicable for us to put an end to our unhappy way of living, and get off?" "Yes," says he, "I think it very practicable." We were then anchored off the city of Bassorah, and one night William and I went ashore, and sent a note to the boatswain telling him we were betrayed and bidding him make off with the ship. By this means we frighted the rogues our comrades; and we had nothing to do then but to consider how to convert our treasure into things proper to make us look like merchants, as we were now to be, and not like freebooters, as we really had been. Then we clothed ourselves like Armenian merchants, and after many days reached Venice; and at last we agreed to go to London. For William had a sister whom he was anxious to see once more. So we came to England, and some time later I married William's sister, with whom I am much more happy than I deserve. * * * * * |