|

|

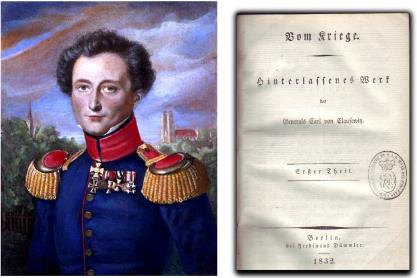

(Vom Kriege) by General Carl Von Clausewitz The original, squashed down to read in about 15 minutes  (Prussia, 1832) Just as Machiavelli 'spilled the beans' on how States really work, General Clausewitz did so for soldiery - pointing out how war, the mere continuation of politics, is not the precisely drilled ballet of popular myth, but a fog-bound mire where no one really knows what is going on. This work became a standard textbook for the military leaders of the 19th and early 20th centuries, and must therefore take some of the blame, thanks to Clausewitz's absolute disinterest in death or distress, for the twenty million fallen of the 1914-1918 war and what Churchill called "that mechanical scattering of death which the polite nations of the earth have brought to such monstrous perfection". Abridged: GH, from the translation by Colonel James John Graham. (Vom Kriege) PREFACE I: THE NATURE OF WAR - War is nothing but a duel on an extensive scale, an act of violence intended to compel our opponent to fulfil our will. Self-imposed restrictions, almost imperceptible and hardly worth mentioning, termed usages of International Law, accompany it without essentially impairing its power. - War is utmost use of force: Philanthropists may imagine there is a method of disarming an enemy without great bloodshed. This is an error. In War, errors from benevolence are the worst. It is to no purpose, even against one's own interest, to turn away from the real nature of the affair because its horror excites repugnance. To introduce into the philosophy of War a principle of moderation would be an absurdity. - Even the most civilized peoples can be fired with passionate hatred for each other. This is a reciprocal action. - The aim is to disarm the enemy: As long as the enemy is not defeated, he may defeat me. This is the second reciprocal action. - If we desire to defeat the enemy, we must proportion our efforts to his powers of resistance. But the adversary does the same. This is the third case of reciprocal action. - The human will does not derive its impulse from logical subtleties. - War is never an isolated act. - War does not consist of a single instantaneous blow. - The result in war is never absolute. The conquered State often sees in it only a passing evil, which may be repaired by politics. - The probabilities of real life replace any absolute conceptions. - The political object: It is quite possible for such a state of feeling to exist between two States that a very trifling political motive may produce a perfect explosion. - Strife can be brought to a standstill by one motive alone, which is, that one party waits for a more favourable moment for action. - Each Commander can only fully know his own position; that of his opponent can only be known to him by uncertain reports. - War is a game both objectively and subjectively. - The Art of War has to deal with living and with moral forces, thus it can never attain the absolute and positive clarity of logic or mathematics. - War is always a serious means for a serious object. But War is no mere passion for venturing and winning. The War of civilised Nations always starts from a political motive. - War is a mere continuation of politics by other means. War is not merely a political act, but also a real political instrument. War is a political act. - The greater and the more powerful the motives of a War, the more it affects the whole existence of a people. - The first, and most decisive judgement of the Statesman and General is rightly to understand the kind of War on which they are embarking. - War is not only chameleon-like, because it forever changes its colour, but it is always a wonderful trinity, of: - The original violence of its elements, hatred and animosity, fruits of blind instinct; - The play of probabilities and chance, which make it a free activity of the soul; - The subordinate nature of a political instrument. - The first of these three concerns more the people, the second, more the General and his Army; the third, more the Government. But the passions which break forth in War must already have a latent existence in the nation. The object of War is as variable as its political objects. But, every case depends on overthrowing the military power, the country, and the will of the enemy. But this complete disarming is rarely attained in practice. Frederick the Great was never strong enough to overthrow the Austrian monarchy, but his skilful husbanding of his resources showed that his strength far exceeded what they had anticipated, so that they made peace. There are many ways to one's object in War; and the complete subjugation of the enemy is not essential in every case. But the enemy acts on the same principle as us; and we must require the commander to remember that the God of War may surprise him; that he ought always to keep his eye on the enemy, in order that he may not have to defend himself with a dress rapier if the enemy takes up a sharp sword. If every combatant was required to be endowed with military genius, then our armies would be very weak. War is the province of danger, and therefore courage, both physical and moral, is the first quality of a warrior. War is the province of physical exertion and suffering, so strength of body and mind is required. War is the province of chance, so resolution is needed. As long as his men are full of courage to fight with zeal, it is seldom necessary for the Chief to show great energy of purpose. But as soon as difficulties arise then things no longer move on like a well-oiled machine, the machine itself begins to offer resistance, and the Commander must have a great force of will. Of all the noble feelings which fill the human heart in the exciting tumult of battle, none are so powerful and constant as the soul's thirst for honour and renown, though, in War the abuse of these proud aspirations must bring about shocking outrages. Other feelings, such as love of country, fanaticism or revenge may rouse the great masses, but they do not give the Leader a desire to will more than others. Now in War, in the harrowing sight of danger and the twilight which surrounds everything, a change of opinion is more conceivable and more pardonable. It is, at all times, only conjecture or guesses at truth which we have to act upon. This is why differences of opinion are nowhere so great as in War. It is here that force of character is needed. Which leads us to a spurious variety of it - obstinacy, or resistance against our better judgement. The Commander in War must use the mental gift known as Orisinn, or sense of locality, and make himself familiar with the geography. For each station, from the lowest upwards, to render distinguished services in War, there must be a particular genius, for Buonaparte was right when he said that many of the questions which come before a General would equal the mathematics of a Newton or an Euler. The military genius is the mind searching rather than inventive, comprehensive rather than specialist, cool rather than fiery. It is to these, in time of War, we should entrust the welfare of our women and children, the honour and the safety of our fatherland. When we first hear of danger, before we know what it is, we find it attractive. To throw oneself, blinded by excitement, against cold death, uncertain whether we shall escape him, and all this close to the golden gate of victory, close to the rich fruit which ambition thirsts for- can this be difficult? Let us accompany the novice to the battle-field. Here, in the close striking of the cannon balls and the bursting of shells, the seriousness of life makes itself visible. We see a friend fall, and know that even the bravest is confused. We see the General, a man of acknowledged courage, keeping carefully behind a rising ground, a house, or a tree. A picture far short of that formed by the student in his chamber! A great part of the information obtained in War is contradictory, a still greater part is false. Everyone is inclined to magnify the bad in some measure, and although the alarms thus propagated subside into themselves like the waves of the sea, still, like them, they rise again. Firm in his own convictions, the Chief must stand like a rock against which the sea breaks its fury in vain. Everything is very simple in War, but the simplest thing is difficult. Activity in War is movement in a resistant medium. Just as a man immersed in water is unable to perform the simplest movement, that of walking, so in War, with ordinary powers, one cannot achieve even mediocrity. This is why absurd theorists, who have never plunged in themselves, teach only what every one knows- how to walk. II: THE THEORY OF WAR WAR means fighting. But fighting is a trial of moral as well as physical forces, and the condition of the mind has always the most decisive influence. - The first "art of war" was merely the preparation of forces. - True war as craft appears in the art of sieges. - Then tactics appeared, and, at first, led to an army like an automaton with rigid formations and orders, intended to unwind like clockwork. - The real conduct of war appeared only incidentally. - Which showed the want of a military theory. - There arose maxims, rules, and even systems for the conduct of war. - Theoretical writers attempted to make war a matter of calculation, but directed their maxims only upon material things and one-sided activity. - Superiority in numbers was chosen from amongst all the factors required to produce victory, because it could be brought under mathematical laws, a restriction overruled by the force of realities. - Victualling of troops was systematised, but only through arbitrary and impractical calculations. - An ingenious author tried to concentrate on a single conception, that of a base for the subsistence of the troops, the keeping them complete in numbers and equipment. - The idea of 'interior lines' is purely geometrical; another one-sided theory. - All these attempts are open to objection. They strive after determinate quantities, whilst in war all is undetermined. - As a rule they exclude genius. Pity the theory which sets itself in opposition to the mind! - The moral quantities must not be excluded in war. War is never directed solely against matter; but always against an intelligent force. Danger in war is like a crystalline lens through which all appearances pass before reaching the understanding. Every one knows the moral effect of a surprise, of an attack in flank or rear. Every one thinks less of the enemy's courage as soon as he turns his back. Every one judges the enemy's General by his reputation, and shapes his course accordingly. Every one casts a scrutinising glance at the spirit and feeling of his own and the enemy's troops. - The first great moral force is the expression of hostile feeling, but in wars, this frequently resolves into merely a hostile view, with no innate hostile feeling residing in individual against individual. National hatred is some substitute for personal hostility, but where this is wanting, a hostile feeling is kindled by the combat itself. - The combat begets danger. Courage is no mere counterpoise to danger, but a peculiar power in itself. - A soldier must become unused to deceit, because it is of no avail against death, and so attain that soldierly simplicity of character which has always been the best representative of the military profession. - The second peculiarity in war is the living reaction, and the reciprocal action resulting therefrom. - Thirdly, the great uncertainty of all data in war is a peculiar difficulty. All action must be planned in a mere twilight, which, like fog or moonshine, gives things exaggerated dimensions. - Thus it is a sheer impossibility to construct a theory of war. - Theory must, therefore, be of the nature of observations, not of doctrine. - There are certain circumstances which attend the combat throughout; the locality, the time of day, and the weather. - Strategy deduces only from experience the ends and means to be examined. - How far should theory go in its analysis of the means. The conduct of war is not making powder and cannon. Strategy makes use of maps without troubling itself about triangulations; it does not inquire how the country is subdivided, how the people are educated and governed; but it takes things as it finds them in the community of european states, and observes where different conditions have an influence on war. - A great simplification of knowledge is required. - As a rule, the most distinguished generals have never risen from the very learned or erudite class of officers. - Knowledge must be suitable to the position. There are field marshals who would not have shone at the head of a cavalry regiment, and vice versa. - The knowledge in war is very simple, but not, at the same time, very easy. It increases in difficulty with increase of rank, and in the highest position, in that of commander-in-chief, is to be reckoned among the most difficult which there is for the human mind. - The commander of an army need not understand the harness of a battery horse, but he must know how to calculate exactly the march of a column. The necessary knowledge for high military position is only to be attained through a special talent which understands how to extract from the phenomena of life only the essence or spirit, as bees take honey from the flowers. Life alone will never bring about a Newton by its rich teachings, but it may bring forth great calculators in war, such as Frederick. - Knowledge must be converted into real power. Science must become art. War is part of the intercourse of the human race, and so belongs not to the Arts and Sciences, but to social life. War is no activity of the will exerted upon inanimate matter like the mechanical Arts, but against a living and reacting force. There is a logical hierarchy through which the world of action is governed. Law is the relation of things and their effects to one another; as a subject of the will, equivalent to command or prohibition. Principle is objective when it is the result of objective truth, and consequently of equal value for all men; it is subjective, and called maxim, if it has value only for the person who makes it. Methodicism is determination by methods instead of principles or prescriptions, founded on the average probability of cases one with another. |