|

|

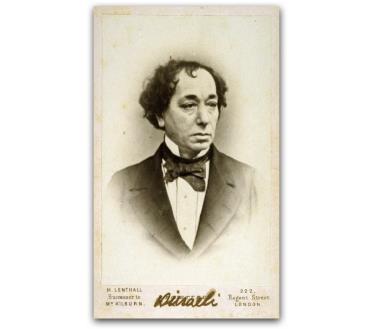

by Benjamin Disraeli The original, squashed down to read in about 30 minutes  (1844) Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield (December 21, 1804, - 1881) was not only a British Conservative Prime Minister, but also a novelist of significant powers. His books reflect his political views and remain important sources for the lives and opinions of the mid-nineteenth century. Abridged: JH For more works by Disraeli, see The Index I. - The Hero of Eton Coningsby was the orphan child of the younger of the two sons of Lord Monmouth. It was a family famous for its hatreds. The elder son hated his father, and lived at Naples, maintaining no connection either with his parent or his native country. On the other hand, Lord Monmouth hated his younger son, who had married against his consent a woman to whom that son was devoted. Persecuted by his father, he died abroad, and his widow returned to England. Not having a relation, and scarcely an acquaintance, in the world, she made an appeal to her husband's father, the wealthiest noble in England, and a man who was often prodigal, and occasionally generous, who respected law, and despised opinion. Lord Monmouth decided that, provided she gave up her child, and permanently resided in one of the remotest counties, he would make her a yearly allowance of three hundred pounds. Necessity made the victim yield; and three years later, Mrs. Coningsby died, the same day that her fatherin-law was made a marquess. Coningsby was then not more than nine years of age; and when he attained his twelfth year an order was received from Lord Monmouth, who was at Rome, that he should go at once to Eton. Coningsby had never seen his grandfather. It was Mr. Rigby who made arrangements for his education. This Mr. Rigby was the manager of Lord Monmouth's parliamentary influence and the auditor of his vast estates. He was a member for one of Lord Monmouth's boroughs, and, in fact, a great personage. Lord Monmouth had bought him, and it was a good purchase. In the spring of 1832, when the country was in the throes of agitation over the Reform Bill, Lord Monmouth returned to England, accompanied by the Prince and Princess Colonna and the Princess Lucretia, the prince's daughter by his first wife. Coningsby was summoned from Eton to Monmouth House, and returned to school in the full favour of the marquess. Coningsby was the hero of Eton; everybody was proud of him, talked of him, quoted him, imitated him. But the ties of friendship bound Coningsby to Henry Sydney and Oswald Millbank above all companions. Lord Henry Sydney was the son of a duke, and Millbank was the son of one of the wealthiest manufacturers in Lancashire. Once, on the river, Coningsby saved Millbank's life; and this was the beginning of a close and ardent friendship. Coningsby liked very much to talk politics with Millbank. He heard things from Millbank which were new to him. Politics had, as yet, appeared to him a struggle whether the country was to be governed by Whig nobles or Tory nobles; and Coningsby, a high Tory as he supposed himself to be, thought it very unfortunate that he should probably have to enter life with his friends out of power and his family boroughs destroyed. But, in conversing with Millbank, he heard for the first time of influential classes in the country who were not noble, and were yet determined to acquire power. Generally, at that time, among the upper boys at Eton there was a reigning inclination for political discussion, and a feeling in favour of "Conservative principles." A year later, and in 1836, gradually the inquiry fell upon attentive ears as to what these Conservative principles were. Before Coningsby and his friends left Eton - Coningsby for Cambridge, and Millbank for Oxford - they were resolved to contend for political faith rather than for mere partisan success or personal ambition. II. - A Portrait of a Lady On his way to Coningsby Castle, in Lancashire, where the Marquess of Monmouth was living in state - feasting the county, patronising the borough, and diffusing confidence in the Conservative party in order that the electors of Dartford might return his man, Mr. Rigby, once more for parliament - our hero halted for the night at Manchester. In the coffee-room at the hotel a stranger, loud in praise of the commercial enterprise of the neighbourhood, advised Coningsby, if he wanted to see something tip-top in the way of cotton works, to visit Millbank of Millbank's; and thus it came about that Coningsby first met Edith Millbank. Oswald was abroad; and Mr. Millbank, when he heard the name of his visitor, was only distressed that the sudden arrival left no time for adequate welcome. "My visit to Manchester, which led to this, was quite accidental," said Coningsby. "I am bound for the other division of the county, to pay a visit to my grandfather, Lord Monmouth, but an irresistible desire came over me during my journey to view this famous district of industry." A cloud passed over the countenance of Millbank as the name of Lord Monmouth was mentioned; but he said nothing, only turning towards Coningsby, with an air of kindness, to beg him, since to stay longer was impossible, to dine with him. Coningsby gladly agreed to this and the village clock was striking five when Mr. Millbank and his guest entered the gardens of his mansion and proceeded to the house. The hall was capacious and classic; and as they approached the staircase the sweetest and the clearest voice exclaimed from above: "Papa, papa!" and instantly a young girl came bounding down the stairs; but suddenly, seeing a stranger with her father, she stopped upon the landing-place. Mr. Millbank beckoned her, and she came down slowly; at the foot of the stairs her father said briefly: "A friend you have often heard of, Edith - this is Mr. Coningsby." She started, blushed very much, and then put forth her hand. "How often have we all wished to see and to thank you!" Miss Edith Millbank remarked in tones of sensibility. Opposite Coningsby at dinner that night was a portrait which greatly attracted his attention. It represented a woman extremely young and of a rare beauty. The face was looking out of the canvas, and the gaze of this picture disturbed the serenity of Coningsby. On rising to leave the table he said to Mr. Millbank, "By whom is that portrait, sir?" The countenance of Millbank became disturbed; his expression was agitated, almost angry. "Oh! that is by a country artist," he said, "of whom you never heard." III. - The Course of True Love The Princess Colonna resolved that an alliance should take place between Coningsby and her step-daughter. But the plans of the princess, imparted to Mr. Rigby that she might gain his assistance in achieving them, were doomed to frustration. Coningsby fell deeply in love with Miss Millbank; and Lord Monmouth himself decided to marry Lucretia. It was in Paris that Coningsby, on a visit to his grandfather, woke to the knowledge of his love for Edith Millbank. They met at a brilliant party, Miss Millbank in the care of her aunt, Lady Wallinger. "Miss Millbank says that you have quite forgotten her," said a mutual friend. Coningsby started, advanced, coloured a little, could not conceal his surprise. The lady, too, though more prepared, was not without confusion. Coningsby recalled at that moment the beautiful, bashful countenance that had so charmed him at Millbank; but two years had effected a wonderful change, and transformed the silent, embarrassed girl into a woman of surpassing beauty. That night the image of Edith Millbank was the last thought of Coningsby as he sank into an agitated slumber. In the morning his first thought was of her of whom he had dreamed. The light had dawned on his soul. Coningsby loved. The course of true love was not to run smoothly with our hero. Within a few days he heard rumours that Miss Millbank was to be married to Sidonia, a wealthy and gifted man of the Jewish race, the friend of Lord Monmouth. Often had Coningsby admired the wisdom and the abilities of Sidonia; against such a rival he felt powerless, and, without mustering courage to speak, left hastily for England. But Coningsby had been deceived - the gossip was without foundation; and once more he was to meet Edith Millbank. This time, however, it was Mr. Millbank himself who vetoed the courtship. Oswald had invited his friend to Millbank; and Coningsby, having learnt the baselessness of the report that had driven him from Paris, gladly accepted. Coningsby Castle was near to Hellingsley; and this estate Mr. Millbank had purchased, outbidding Lord Monmouth. Bitter enmity existed between the great marquess and the famous manufacturer - an old, implacable hatred. Mr. Millbank now resided at Hellingsley; and Coningsby left the castle rejoicing to meet his old Eton friend again, and still more the beautiful sister of his old friend. Mr. Millbank was from home when he arrived; and Coningsby and Miss Millbank walked in the park, and rested by the margin of a stream. Assuredly a maiden and a youth more beautiful and engaging had seldom met in a scene more fresh and fair. Coningsby gazed on the countenance of his companion. She turned her head, and met his glance. "Edith," he said, in a tone of tremulous passion, "let me call you Edith! Yes," he continued, gently taking her hand; "let me call you my Edith! I love you!" She did not withdraw her hand; but turned away a face flushed as the impending twilight. The lovers returned late for dinner to find that Mr. Millbank was at home. Next morning, in Mr. Millbank's room, Coningsby learnt that the marriage he looked forward to with all the ardour of youth was quite impossible. "The sacrifices and the misery of such a marriage are certain and inseparable," said Mr. Millbank gravely, but without harshness. "You are the grandson of Lord Monmouth; at present enjoying his favour, but dependent on his bounty. You may be the heir of his wealth to-morrow and to-morrow you may be the object of his hatred and persecution. Your grandfather and myself are foes - to the death. It is idle to mince phrases. I do not vindicate our mutual feelings; I may regret that they have ever arisen, especially at this exigency. Lord Monmouth would crush me, had he the power, like a worm; and I have curbed his proud fortunes often. These feelings of hatred may be deplored, but they do not exist; and now you are to go to this man, and ask his sanction to marry my daughter!" "I would appease these hatreds," retorted Coningsby, "the origin of which I know not. I would appeal to my grandfather. I would show him Edith." "He has looked upon as fair even as Edith," said Mr. Millbank. "And did that melt his heart? My daughter and yourself can meet no more." In vain Coningsby pleaded his suit. It was not till Mr. Millbank told that he, too, had suffered - that he had loved Coningsby's own mother, and that she gave her heart to another, to die afterwards solitary and forsaken, tortured by Lord Monmouth - that Coningsby was silent. It was his mother's portrait he had looked upon that night at Millbank; and he understood the cause of the hatred. He wrung Mr. Millbank's hand, and left Hellingsley in despair. But Oswald overtook him in the park; and, leaning on his friend's arm, Coningsby poured forth a hurried, impassioned, and incoherent strain-all that had occurred, all that he had dreamed, his baffled bliss, his actual despair, his hopeless outlook. A thunderstorm overtook them; and Oswald took refuge from the elements at the castle. There, as they sat together, pledging their faithful friendship, the door opened, and Mr. Rigby appeared. IV. - Coningsby's Political Faith Lord Monmouth banished the Princess Colonna from his presence, and married Lucretia. Coningsby returned to Cambridge, and continued to enjoy his grandfather's hospitality whenever Lord Monmouth was in London. Mr. Millbank had, in the meantime, become a member of parliament, having defeated Mr. Rigby in the contest for the representation of Dartford. In the year 1840 a general election was imminent, and Lord Monmouth returned to London. He was weary of Paris; every day he found it more difficult to be amused. Lucretia had lost her charm: they had been married nearly three years. The marquess, from whom nothing could be concealed, perceived that often, while she elaborately attempted to divert him, her mind was wandering elsewhere. He fell into the easy habit of dining in his private rooms, sometimes tête-à-tête with Villebecque, his private secretary, a cosmopolitan theatrical manager, whose tales and adventures about a kind of society which Lord Monmouth had always preferred to the polished and somewhat insipid circles in which he was born, had rendered him the prime favourite of his great patron. Villebecque's step-daughter Flora, a modest and retiring maiden, waited on Lucretia. Back in London, Lord Monmouth, on the day of his arrival, welcomed Coningsby to his room, and at a sign from his master Villebecque left the apartment. "You see, Harry," said Lord Monmouth, "that I am much occupied to-day, yet the business on which I wish to communicate with you is so pressing that it could not be postponed. These are not times when young men should be out of sight. Your public career will commence immediately. The government have resolved on a dissolution. My information is from the highest quarter. The Whigs are going to dissolve their own House of Commons. Notwithstanding this, we can beat them, but the race requires the finest jockeying. We can't give a point. Now, if we had a good candidate, we could win Dartford. But Rigby won't do. He is too much of the old clique used up a hack; besides, a beaten horse. We are assured the name of Coningsby would be a host; there is a considerable section who support the present fellow who will not vote against a Coningsby. They have thought of you as a fit person; and I have approved of the suggestion. You will, therefore, be the candidate for Dartford with my entire sanction and support; and I have no doubt you will be successful." To Coningsby the idea was appalling. To be the rival of Mr. Millbank on the hustings of Dartford! Vanquished or victorious, equally a catastrophe. He saw Edith canvassing for her father and against him. Besides, to enter the House of Commons a slave and a tool of party! Strongly anti-Whig, Coningsby distrusted the Conservative party, and looked for a new party of men who shared his youthful convictions and high political principles. Lord Monmouth, however, brushed aside his grandson's objections. "You are certainly still young; but I was younger by nearly two years when I first went in, and I found no difficulty. As for your opinions, you have no business to have any other than those I uphold. I want to see you in parliament. I tell you what it is, Harry," Lord Monmouth concluded, very emphatically, "members of this family may think as they like, but they must act as I please. You must go down on Friday to Dartford and declare yourself a candidate for the town, or I shall reconsider our mutual positions." Coningsby left Monmouth House in dejection, but to his solemn resolution of political faith he remained firm. He would not stand for Dartford against Mr. Millbank as the nominee of a party he could not follow. In terms of tenderness and humility he wrote to his grandfather that he positively declined to enter parliament except as the master of his own conduct. In the same hour of his distress Coningsby overheard in his club two men discussing the engagement of Miss Millbank to the Marquess of Beaumanoir, the elder brother of his school friend, Henry Sydney. Edith Millbank, too, had heard news at a London assembly of wealth and fashion that Coningsby was engaged to be married to Lady Theresa Sydney. So easily does rumour spin her stories and smite her victims with sadness. V. - Lady Monmouth's Departure It was Flora, to whom Coningsby had been always kind and courteous, who told Lucretia that Lord Monmouth was displeased with his grandson. "My lord is very angry with Mr. Coningsby," she said, shaking her head mournfully. "My lord told M. Villebecque that perhaps Mr. Coningsby would never enter the house again." Lucretia immediately dispatched a note to Mr. Rigby, and, on the arrival of that gentleman, told him all she had learnt of the contention between Harry Coningsby and her husband. "I told you to beware of him long ago," said Lady Monmouth. "He has ever been in the way of both of us." "He is in my power," said Rigby. "We can crush him. He is in love with the daughter of Millbank, the man who bought Hellingsley. I found the younger Millbank quite domiciliated at the castle, a fact which of itself, if known to Lord Monmouth, would ensure the lad's annihilation." "The time is now most mature for this. Let us not conceal it from ourselves that since this grandson's first visit to Coningsby Castle we have neither of us really been in the same position with my lord which we then occupied, or believed we should occupy. Go now; the game is before you! Rid me of this Coningsby, and I will secure all that you want." "It shall be done," said Rigby, "it must be done." Lady Monmouth bade Mr. Rigby hasten at once to the marquess and bring her news of the interview. She awaited with some excitement his return. Her original prejudice against Coningsby and jealousy of his influence had been aggravated by the knowledge that, although after her marriage Lord Monmouth had made a will which secured to her a very large portion of his great wealth, the energies and resources of the marquess had of late been directed to establish Coningsby in a barony. Two hours elapsed before Mr. Rigby returned. There was a churlish and unusual look about him. "Lord Monmouth suggests that, as you were tired of Paris, your ladyship might find the German baths at Kissingen agreeable. A paragraph in the 'Morning Post' would announce that his lordship was about to join you; and even if his lordship did not ultimately reach you, an amicable separation would be effected." In vain Lucretia stormed. Mr. Rigby mentioned that Lord Monmouth had already left the house and would not return, and finally announced that Lucretia's letters to a certain Prince Trautsmandorff were in his lordship's possession. A few days later, and Coningsby read in the papers of Lady Monmouth's departure to Kissingen. He called at Monmouth House, to find the place empty, and to learn from the porter that Lord Monmouth was about to occupy a villa at Richmond. Coningsby entertained for his grandfather a sincere affection. With the exception of their last unfortunate interview, he had experienced nothing but kindness from Lord Monmouth. He determined to pay him a visit at Richmond. Lord Monmouth, who was entertaining two French ladies at his villa, recoiled from grandsons and relations and ties of all kinds; but Coningsby so pleasantly impressed his fair visitors that Lord Monmouth decided to ask him to dinner. Thus, in spite of the combinations of Lucretia and Mr. Rigby, and his grandfather's resentment, within a month of the memorable interview at Monmouth House, Coningsby found himself once more a welcome guest at Lord Monmouth's table. In that same month other important circumstances also occurred. At a fête in some beautiful gardens on the banks of the Thames, Coningsby and Edith Millbank were both present. The announcement was made of the forthcoming marriage of Lady Theresa Sydney to Mr. Eustace Lyle, a friend of Mr. Coningsby; and later, from the lips of Lady Wallinger herself, Miss Millbank's aunt, Coningsby learnt how really groundless was the report of Lord Beaumanoir's engagement. "Lord Beaumanoir admires her - has always admired her," Lady Wallinger explained to Coningsby; "but Edith has given him no encouragement whatever." At the end of the terrace Edith and Coningsby met. He seized the occasion to walk some distance by her side. "How could you ever doubt me?" said Coningsby, after some time. "I was unhappy." "And now we are to each other as before." "And will be, come what may," said Edith. VI. - Lord Monmouth's Money In the midst of Christmas-revels at the country house of Mr. Eustace Lyle, surrounded by the duke and duchess and their children - the Sydneys - Coningsby was called away by a messenger, who brought news of the sudden death of Lord Monmouth. The marquess had died at supper at his Richmond villa, with no persons near him but those who were very amusing. The body had been removed to Monmouth House; and after the funeral, in the principal saloon of Monmouth House, the will was eventually read. The date of the will was 1829; and by this document the sum of £10,000 was left to Coningsby, who at that time was unknown to his grandfather. But there were many codicils. In 1832, the £10,000 was increased to £50,000. In 1836, after Coningsby's visit to the castle, £50,000 was left to the Princess Lucretia, and Coningsby was left sole residuary legatee. After the marriage, an estate of £9,000 a year was left to Coningsby, £20,000 to Mr. Rigby, and the whole of the residue went to issue by Lady Monmouth. In the event of there being no issue, the whole of the estate was to be divided equally between Lady Monmouth and Coningsby. In 1839, Mr. Rigby was reduced to £10,000, Lady Monmouth was to receive £3,000 per annum, and the rest, without reserve, went absolutely to Coningsby. The last codicil was dated immediately after the separation with Lady Monmouth. All dispositions in favour of Coningsby were revoked, and he was left with the interest of the original £10,000, the executors to invest the money as they thought best for his advancement, provided it were not placed in any manufactory. Mr. Rigby received £5,000, M. Villebecque £30,000, and all the rest, residue and remainder, to Flora, commonly called Flora Villebecque, step-child of Armand Villebecque, "but who is my natural daughter by an actress at the Théâtre Français in the years 1811-15, by the name of Stella." Sidonia lightened the blow for Coningsby as far as philosophy could be of use. "I ask you," he said, "which would you have rather lost - your grandfather's inheritance or your right leg?" "Most certainly my inheritance." "Or your left arm?" "Still the inheritance." "Would you have given up a year of your life for that fortune trebled?" "Even at twenty-three I would have refused the terms." "Come, then, Coningsby, the calamity cannot be very great. You have health, youth, good looks, great abilities, considerable knowledge, a fine courage, and no contemptible experience. You can live on £300 a year. Read for the Bar." "I have resolved," said Coningsby. "I will try for the Great Seal!" Next morning came a note from Flora, begging Mr. Coningsby to call upon her. It was an interview he would rather have avoided. But Flora had not injured him, and she was, after all, his kin. She was alone when Coningsby entered the room. "I have robbed you of your inheritance." "It was not mine by any right, legal or moral. The fortune is yours, dear Flora, by every right; and there is no one who wishes more fervently that it may contribute to your happiness than I do." "It is killing me," said Flora mournfully. "I must tell you what I feel. This fortune is yours. I never thought to be so happy as I shall be if you will generously accept it." "You are, as I have ever thought you, the kindest and most tender-hearted of beings," said Coningsby, much moved; "but the custom of the world does not permit such acts to either of us as you contemplate. Have confidence in yourself. You will be happy." "When I die, these riches will be yours; that, at all events, you cannot prevent," were Flora's last generous words. VII. - On Life's Threshold Coningsby established himself in the Temple to read law; and Lord Henry Sydney, Oswald Millbank, and other old Eton friends rallied round their early leader. "I feel quite convinced that Coningsby will become Lord Chancellor," Henry Sydney said gravely, after leaving the Temple. The General Election of 1841, which Lord Monmouth had expected a year before, found Coningsby a solitary student in his lonely chambers in the Temple. All his friends and early companions were candidates, and with sanguine prospects. They sent their addresses to Coningsby, who, deeply interested, traced in them the influence of his own mind. Then, in the midst of the election, one evening in July, Coningsby, catching up a third edition of the "Sun," was startled by the word "Dartford" in large type. Below it were the headlines: "Extraordinary Affair! Withdrawal of the Liberal Candidate! Two Tory Candidates in the Field!" Mr. Millbank, at the last moment, had retired, and had persuaded his supporters to nominate Harry Coningsby in his place. The fight was between Coningsby and Rigby. Oswald Millbank, who had just been returned to parliament, came up to London; and from him, as they travelled to Dartford, Coningsby grasped the change of events. Sidonia had explained to Lady Wallinger the cause of Coningsby's disinheritance. Lady Wallinger had told Oswald and Edith; and Oswald had urged on his father the recognition of his friend's affection for his sister. On his own impulse Mr. Millbank decided that Coningsby should contest Dartford. Mr. Rigby was beaten; and Coningsby arrived at Dartford in time to receive the cheers of thousands. From the hustings he gave his first address to a public assembly; and by general agreement no such speech had ever been heard in the borough before. Early in the autumn Harry and Edith were married at Millbank, and they passed their first moon at Hellingsley. The death of Flora, who had bequeathed the whole of her fortune to the husband of Edith, took place before the end of the year, hastened by the fatal inheritance which disturbed her peace and embittered her days, haunting her heart with the recollection that she had been the instrument of injuring the only being whom she loved. Coningsby passed his next Christmas in his own hall, with his beautiful and gifted wife by his side, and surrounded by the friends of his heart and his youth. The young couple stand now on the threshold of public life. What will be their fate? Will they maintain in august assemblies and high places the great truths, which, in study and in solitude, they have embraced? Or will vanity confound their fortunes, and jealousy wither their sympathies? * * * * * |