|

|

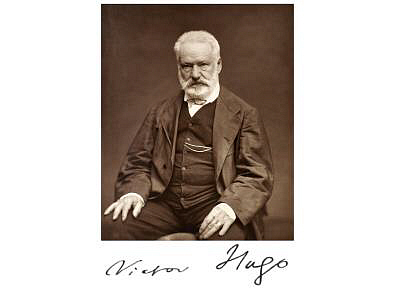

(Actes et Paroles) by Victor Hugo The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (Paris, 1885) Victor Marie Hugo was born on 26th February 1802 at the ancient city of Besançon in Eastern France. His political views were firm and radical, though somewhat variable. Hugo was elevated to the peerage by King Louis-Philippe, but his opposition to Louis Napoleon's seizing power in 1851 led to his exile in Jersey, from where he was, in turn, expelled for criticising Queen Victoria. He finally settled in Guernsey, returning to France in 1870 as a significant national hero. Abridged: JH/GH For more books by Victor Hugo, see The Index I. - Right and Law All human eloquence, among all peoples and in all times, may be summed up as the quarrel of Right against Law. But this quarrel tends ever to decrease, and therein lies the whole of progress. On the day when it has disappeared, civilisation will have attained its highest point; that which ought to be will have become one with that which is; there will be an end of catastrophes, and even, so to speak, of events; and society will develop majestically according to nature. There will be no more disputes nor factions; no longer will laws be made, they will only be discovered. Education will have taken the place of war, and by means of universal suffrage there will be chosen a parliament of intellect. In that serene and glorious age there will be no more warriors, but workers only; creators in the place of exterminators. The civilisation of action will have passed away, and that of thought will have succeeded. The masterpieces of art and of literature will be the great events. Frontiers will disappear; and France, which is destined to die as the gods die, by transfiguration, will become Europe. For the Revolution of France will be known as the evolution of the peoples. France has laboured not for herself alone, but has aroused world-wide hopes, and is herself the representative of all human good-will. Right and Law are the two great forces whose harmony gives birth to order, but their antagonism is the source of all catastrophe. Right is the divine truth, and Law is the earthly reality; liberty is Right and society is Law. Wherefore there are two tribunes, one of the men of ideas, the other of the men of facts; and between these two the consciences of most still vacillate. Not yet is there harmony between the immutable and the variable power; Right and Law are in ceaseless conflict. To Right belong the inviolability of human life, liberty, peace; and nothing that is indissoluble, irrevocable, or irreparable. To Law belong the scaffold, sword, and sceptre; war itself; and every kind of yoke, from divorceless marriage in the family to the state of siege in the city. Right is to come and go, buy, sell, exchange; Law has its frontiers and its custom-houses. Right would have free and compulsory education, without encroaching on young consciences; that is to say, lay instruction; Law would have the teaching of ignorant friars. Right demands liberty of belief, but Law establishes the state religions. Universal suffrage and universal jury belong to Right, but restricted franchise and packed juries are creatures of the Law. What a difference there is! And let it be understood that all social agitation arises from the persistence of Right against the obstinacy of Law. The keynote of the present writer's public life has been "Pro jure contra legem" - for the Right which makes men, against the Law which men have made. He believes that liberty is the highest expression of Right, and that the republican formula, "Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity," leaves nothing to be added or to be taken away. For Liberty is Right, Equality is Fact, and Fraternity is Duty. The whole of man is there. We are brothers in our life, equal in birth and death, free in soul. II. - Days of Childhood At the beginning of this nineteenth century there was a child who lived in a great house, surrounded by a large garden, in the most deserted part of Paris. He lived with his mother, two brothers, and a venerable and worthy priest, who was his only tutor, and taught him much Latin, a little Greek, and no history at all. Here, at the time of the First Empire, the three boys played and worked, watched the clouds and trees and listened to the birds, under the sweet influence of their mother's smile. It was the child's misfortune, though no one's fault, that he was taught by a priest. What can be more terrible than a system of untruth, sincerely believed? For a priest teaches falsehoods, ignorant of the truth, and thinks he does well; everything he does for the child is done against the child, making crooked that which nature has made straight; his teaching poisons the young mind with aged prejudices, drawing evening twilight, like a curtain, over the dawn. That ancient, solitary house and garden, formerly a convent and then the home of his childhood, is still in his old age a dear and religious memory, though its site is now profaned by a modern street He sees it in a romantic atmosphere, in which, amid sunbeams and roses, his spirit opened into flower. What a stillness was in its vast rooms and cloisters. Only at long intervals was the silence broken by the return of a plumed and sabred general, his father, from the wars. That child, already thoughtful, was myself. One night - it was some great festival of the empire, and all Paris was illumined - my mother was walking in the garden with three of my father's comrades, and I was following them, when we saw a tall figure in the gloom of the trees. It was the proscribed Victor du Lahorie, my godfather. He was even then conspiring against Bonaparte in the cause of liberty, and was shortly after executed. I remember his saying, "If Rome had kept her kings, she had not been Rome," and then, looking on me, "Child, put liberty first of all!" That one word outweighed my whole education. III. - Before the Exile It was not until the writer saw, in 1848, the triumph of all the enemies of progress that he knew in the depths of his heart that he belonged, not to the conquerors, but to the vanquished. The Republic lay inanimate; but, gazing on her form, he saw that she was liberty, and not even the sure fore-knowledge of the ruin and exile that must follow could prevent his espousal with the dead. On June 15 he made his protest from the tribune, and from that day he fought relentless battle for liberty and the republic. And on December 2, 1851, he received what he had expected - twenty years of exile. That is the history of what has been called his apostasy. Throughout that strange period before his exile, the frightful phantom of the past was all-powerful with men. Every kind of question was debated - national independence, individual liberty, liberty of conscience, of thought, of speech, and of the Press; questions of marriage, of education, of the right to work, of the right to one's fatherland as against exile, of the right to life as against penal law, of the separation of Church and state, of the federation of Europe, of frontiers to be wiped out, and of custom-houses to be done away - all these questions were proposed, debated, and sometimes settled. In these debates the author of this memoir took his part and did his duty, and was repaid with insults. He remembers interjecting, when they were insisting on parental rights, that the children had rights, too. He astounded the assembly by asserting that it was possible to do away with misery. On July 17, 1851, he denounced the conspiracy of Louis Bonaparte, unveiling the project of the president to become emperor. On another day he pronounced from the tribune a phrase which had never yet been uttered - "The United States of Europe." Contempt and calumny were poured upon him, but what of that? They called George Washington a pickpocket. These men of the old majority, who were doing all the evil that they could - did they mean to do evil? Not a bit of it. They deceived themselves, thinking that they had the truth, and they lied in the service of the truth. Their pity for society was pitiless for the people, whence arose so many laws, so many actions, that were blindly ferocious. They were rather a mob than a senate, and were led by the worst of their number. Let us be indulgent, and let night hide the men of night. What do our labours and our troubles and our exiles matter if they have been for the general good; if the human race be indeed passing from December to its April; if the winter of tyrannies and of wars indeed be finished; if superstitions and prejudices no longer fall on our heads like snow; and if, after so many clouds of empire and of carnage have rolled away, we at last descry upon the horizon the rosy dawn of universal peace? O my brothers, let us be reconciled! Let us set out on the immense highway of peace. Surely there has been enough of hatred. When will you understand that we are all together on the same ship, and that the immense menace of the sea is for all of us together? Our solidarity is terrible, but brotherhood is sweet. IV. - Republican Principles The sovereignty of the people, universal suffrage, and the liberty of the Press are all the same thing under three different names. The three together constitute the whole of our public right; the first is its principle, the second its manner, and the third its expression. The three principles are indissoluble from one another. The sovereignty of the people is the life-giving soul of the nation, universal suffrage its government, the Press its illumination; but they are all really one, and that unity is the republic. It is curious to notice how these principles appear again in the watchword of the republic; for the sovereignty of the people creates liberty, universal suffrage creates equality, and the Press, which enlightens the general mind, creates fraternity. Wherever these three great principles exist in their powers and plenitude there is the republic, even though it be known as monarchy. Wherever, on the other hand, they are betrayed, hindered, or oppressed, the actual state is a monarchy or an oligarchy, even though it goes under the name of a republic. In the latter case we see the monstrous phenomenon of a government betrayed by its proper guardians, and it is this phenomenon that makes the stoutest hearts begin to be doubtful of revolutions. For revolutions are vast, ill-guided movements, which bring forth out of the darkness at one and the same time the greatest of ideas and the smallest of men; they are movements which we welcome as salutary when we look at their principles, but which we can only call catastrophes when he consider the character of their leaders. Let us never forget that our three first principles live with a common life, and mutually defend one another. If the Liberty of the Press is in danger, the suffrages of the people arise and protect it; and, again, if the franchise is threatened, it is safeguarded by the freedom of the Press. Any attempt against either of them is a treachery to the sovereignty of the people. The movement of this great nineteenth century is the movement not of one people only, but of all. France leads, and the nations follow. We are passing from the old world to the new, and our governors attempt in vain to arrest ideas by laws. There is in France and in Europe a party inspired by fear, which is not to be accounted the party of order; and its incessant question is: Who is to blame? In the crisis through which we are passing, though it is a salutary crisis which will lead only to good, everyone exclaims at the dreadful moral disorder and the imminent social danger. Who, then, is guilty of these ravages? Whom shall we punish? Throughout Europe, the party of fear answers "France." Throughout France, it answers "Paris." In Paris, it blames the Press. But every thoughtful man must see that it is none of these, but is the human spirit. It is the human spirit that has made the nations what they are. From the beginning, through infinite debate and contradiction, it has sought, unresting, to solve the problem eternally placed before the creature by his Creator. It is the human spirit which takes from age to age the form of the great revolts of history; it has been in turn, and sometimes altogether, error, illusion, heresy, schism, protest, and the truth. The human spirit is ever the great shepherd of the generations, proceeding always towards the just, the beautiful, and the true, enlightening the multitude, ennobling souls, directing the mind of man towards God. Let the party of fear throughout Europe consider the magnitude of the task which they have undertaken. When they have destroyed the Press, they have yet to destroy Paris. When Paris is fallen, there remains France. Let France be annihilated, there still remains the human spirit - a thing intangible as the light, inaccessible as the sun. V. - In Exile Nothing is more terrible than exile. I do not say for him who suffers, but for the tyrant who inflicts it. A solitary figure paces a distant shore, or rises in the morning to his philosophic labours, or calls on God among the rocks and trees; his hairs become grey, and then white, in the slow passing of the years and in his longing for home; his lot is a sorrowful one; but his innocence is terrible to the crowned miscreant who sent him there. From 1852 to 1870 I was in exile. How pleasant are those islands of the Channel, and how like France! Jersey, perhaps, more charming than Guernsey, prettier if less imposing; in Jersey the forest has become a garden; the island is like a bouquet of flowers, of the size of London, a smiling land, an idyll set in the midst of the sea. The exile soon learns that, though the tyrant has placed him afar, he does not release his hold. Many and ingenious are the snares laid for the banished. A prince calls on you, but though he is of royal blood, he is also a detective of police. A grave professor stays at your house, and you surprise him searching your papers. Everything is permitted against you; you are outside the law, outside of common justice, outside of respect. They will say that they have your authority to publish your conversations, and will attribute to you words that you have never spoken and actions that you have never done. Never write to your friends - your letters are opened on the way. Beware of all who are kindly to you in exile; they are ruining you in Paris. You are isolated as a leper. A mysterious stranger whispers in your ear that he can procure the assassination of Bonaparte; it is Bonaparte offering to kill himself. Every day of your life is a new outrage. Only one thing is open to the exile; it is to turn his thought to other subjects. He is at least beside the sea; let its infinity bring him wisdom. The eternal rioting of the surges against the rocks is as the agitation of impostures against the truth. It is a vain convulsion; the foam gains nothing by it, the granite loses nothing, and only sparkles the more bravely in the sun. But exile has this great advantage - one is free to contemplate, to think, to suffer. To be alone, and yet to feel that one is with all humanity; to consolidate oneself as a citizen, and to purify oneself as a philosopher; to be poor, and begin again to work for one's living, to meditate on what is good and to contrive for what is better; to be angry in the public cause, but to crush all personal enmity; to breathe the vast, living winds of the solitudes; to compose a deeper indignation with a profounder peace - these are the opportunities of exile. I accustomed myself to say, "If, after a revolution, Bonaparte should knock at my door and ask shelter, let never a hair of his head be injured." Yes, an exile becomes a well-wisher. He loves the roses, and the birds' nests, and the flitting hither and thither of the butterflies. He mingles with the sweet joys of the creatures, and learns a changeless faith in some secret and infinite goodness. The green glades are his chosen dwelling and his life is April; he reclines amazed at the mysteries of a tuft of grass; he studies the ant-hills of tiny republicans; he learns to know the birds by their songs; he watches the children playing barefoot in the edge of the sea. Against this dangerous man governments are taking the most strenuous precautions. Victoria offers to hand over the exiles to Napoleon, and messages of compliment are passed from one throne to the other. But that gift did not take place. The English royalist Press applauded, but the people of London would have none of it. The great city muttered thunder. Majesty clothed in probity - that is the character of the English nation. That good and proud people showed their indignation, and Palmerston and Bonaparte had to be content with the expulsion of the exiles. During the whole long night of my exile I never lost Paris from my view. When Europe and even France were in darkness, Paris was never hidden. That is because Paris is the frontier of the future, the visible frontier of the unknown. All of to-morrow that can be seen to-day is in Paris. The eyes that are searching for progress come to rest on Paris, for Paris is the city of light. VI. - After the Exile This triology, "Before, During, and After the Exile," is no work of mine, it is the doing of Napoleon III. He it is who has divided my life in this way, observing, as one might say, the rules of art. Returning to my country on September 5, 1870, I found the sky more gloomy and my duty more clamant than ever. Though it is sad to leave the fatherland, to return to it is sometimes sadder still; and there is no Frenchman who would not have preferred a life-long banishment, to seeing France ground beneath the Prussian heel, and the loss of Metz and Strasburg. This was an invasion of barbarians; but there is another menace that is not less formidable. I mean the invasion of our land by darkness, an invasion of the nineteenth century by the middle ages. After the emperor, the pope; after Berlin, Rome; after the triumph of the sword, the triumph of night. For the light of civilisation may be extinguished in either of two ways, by a military or by a clerical invasion. The former threatens our mother, France; the latter our child, the future. A double inviolability is the most precious possession of a civilised people - the inviolability of territory and the inviolability of conscience; and as the soldier violates the first, so does the priest violate the other. Yet the soldier does but obey his orders and the priest his dogmas, so that there are only two who are ultimately culpable - Caesar, who slays, and Peter, who lies. There is no religion which has not as its aim to seize forcibly the human soul, and it is to attempts of this kind that France is given up to-day. One may say, indeed, that in our age there are two schools, and that these two schools sum up in themselves the two opposed currents which draw civilisation, the one towards the future and the other towards the past. One of these schools is called Paris and the other Rome. Each of them has its book; the one has the "Declaration of the Rights of Man," the other has the "Syllabus"; and the first of these books says "Yes" to progress, but the second of them says "No." Yet progress is the footstep of God. Paris means Montaigne, Rabelais, Pascal, Corneille, Molière, Montesquieu, Diderot, Rousseau, Voltaire, Mirabeau, Danton. Rome, on the other hand, means Innocent III., Pius V., Alexander VI., Urban VIII., Arbuez, Cisneros, Lainez, Guillandus, Ignatius. To educate is nothing less than to govern; and clerical education means a clerical government, with a despotism as its summit and ignorance as its foundation. Rome already holds Belgium, and would now seize Paris. We are witnesses of a struggle to the death. Against us is all that manifold power which emerges from the past, the spirit of monarchy, of superstition, of the barrack and of the convent; we have against us temerity, effrontery, audacity, and fear. On our side there is nothing but the light. That is why the victory will be with us. For to enlighten is to deliver. Every increase in liberty involves increased responsibility. Nothing is graver than freedom; liberty has burdens of her own, and lays on the conscience all the chains which she unshackles from the limbs. We find rights transforming themselves into duties. Let us therefore take heed to what we are doing; we live in a difficult time and are answerable at once to the past and to the future. The time has come, in this year 1876, to replace commotions by concessions. That is how civilisation advances. For progress is nothing other than revolution effected amicably. Therefore, legislators and citizens, let us redouble our good-will. Let all wounds be healed, all animosities extinguished; by overcoming hatred we shall overcome war; let no disturbance that may come be due to our fault. Our task of entering into the unknown is difficult enough without angers and bitterness. I am one of those who hope from that unknown future, but only on condition that we make use from the first of every means of pacification that is in our power. Let us act with the virile kindness of the strong. Let us then calm the nations by peace, and the hearts of men by brotherhood, and let us never forget that we are ourselves responsible for this last half of the nineteenth century, and that we are placed between a great past, the Revolution of France, and a great future, the Revolution of Europe. * * * * * |