|

|

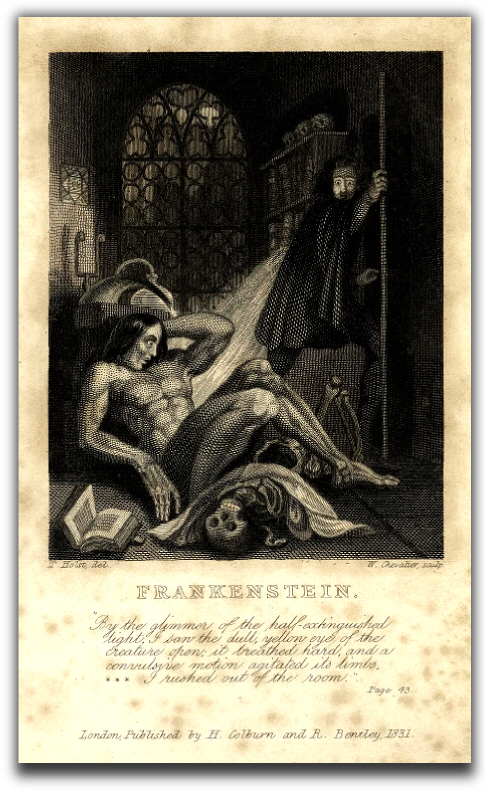

or, The Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley The original, squashed down to read in about 30 minutes  (London, 1818) 1816 was the "Year Without a Summer", a long volcanic winter caused by the eruption of Mount Tambora. On holiday in Switzerland the 19 year-old Mary Godwin, (daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft) her lover the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron amused themselves by inventing horror stories. Byron came up with 'The Vampyre' and Mary with 'Frankenstein'. Although precisely how Dr. Frankenstein gave life to a dead body is left to the imagination of future film-makers, it seems that Mary was influenced by Anton Mesmer's claims to have discovered a life-force of 'animal magnetism' and the attempts of Erasmus Darwin (Charles' grandfather) and others to animate dead matter using electricity. It is one of the great 'Gothic' novels and a continuing warning against human ambition in the industrial age. Abridged: GH or, The Modern Prometheus Robert Walton's Letter August 5, 17-; My Dear Sister. This letter will reach England by a merchantman now on its homeward voyage from Archangel; more fortunate than I, who may not see my native land, perhaps for many years. We have already reached a very high latitude, and it is the height of summer; but last Monday, July 31, we were nearly surrounded by ice which closed in the ship on all sides. Our situation was somewhat dangerous, especially as we were compassed round by a very thick fog. About two o'clock the mist cleared away, and we beheld in every direction, vast and irregular plains of ice. A strange sight suddenly attracted our attention. We perceived a low carriage, fixed on a sledge and drawn by dogs, pass on towards the North: a being which had the shape of a man, but apparently of gigantic stature, sat in the sledge and guided the dogs. We watched the rapid progress of the traveller until he was lost among the distant inequalities of the ice. Before night the ice broke and freed our ship. In the morning, as soon as it was light, I went upon deck, and found all the sailors apparently talking to some one in the sea, it was, in fact, a sledge, like that we had seen before, which had drifted towards us in the night, on a large fragment of ice. Only one dog remained alive, but there was a human being whom the sailors were persuading to enter the vessel. On perceiving me, the stranger addressed me in English. "Before I come on board your vessel," said he, "will you have the kindness to inform me whither you are bound?" I replied that we were on a voyage of discovery towards the northern pole. Upon hearing this he consented to come on board. His limbs were nearly frozen, and his body dreadfully emaciated. I never saw a man in so wretched a condition, and I often feel that his sufferings had deprived him of understanding. Once the lieutenant asked why he had come so far upon the ice in so strange a vehicle. He replied, "To seek one who fled from me." "And did the man whom you pursued travel in the same fashion?" "Yes." "Then I fancy we have seen him; for the day before we picked you up, we saw some dogs drawing a sledge, with a man in it, across the ice." From this time a new spirit of life animated the decaying frame of the stranger. He manifested the greatest eagerness to be upon deck, to watch for the sledge which had before appeared. August 17; Yesterday the stranger said to me, "You may easily perceive, Capt. Walton, that I have suffered great and unparalleled misfortunes. My fate is nearly fulfilled. I wait but for one event, and then I shall repose in peace. Listen to my history, and you will perceive how irrevocably my destiny is determined." Frankenstein's Story I am by birth a Genevese; and my family is one of the most distinguished of that republic. My father has filled several public situations with honour and reputation. He passed his younger days perpetually occupied by the affairs of his country, and it was not until the decline of life that he became a husband and the father of a family. When I was about five years old, my mother, whose benevolent disposition often made her enter the cottages of the poor, brought to our house a child fairer than pictured cherub, an orphan whom she found in a peasant's hut; the infant daughter of a nobleman who had died fighting for Italy. Thus Elizabeth became the inmate of my parents' house. Every one loved her, and I looked upon Elizabeth as mine, to protect, love, and cherish. We called each other familiarly by the name cousin, and were brought up together. No human being could have passed a happier childhood than myself. While I followed the routine of education in the schools of Geneva, I was, to a great degree, self-taught. Under the guidance of my books I searched for the philosopher's stone and the elixir of life. Wealth was an inferior object, but what glory would attend the discovery if I could banish disease from the human frame! Nor were these my only visions. The raising of ghosts or devils was a promise liberally accorded by my favourite authors, the fulfilment of which I most eagerly sought, guided by an ardent imagination and childish reasoning, till an accident again changed the current of my ideas. When I was about fifteen years old we witnessed a most violent and terrible thunderstorm as it advanced from behind the mountains of Jura. I beheld a stream of fire issue from an old oak about twenty yards from our house; and so soon as the dazzling light vanished, we found the tree entirely reduced to thin ribbons of wood. I never beheld anything so utterly destroyed. On this occasion a man of great research in natural philosophy was with us, and he entered on the explanation of a theory of electricity and galvanism, which was at once new and astonishing to me. When I had attained the age of seventeen, my parents resolved that I should become a student at the University of Ingolstadt; I had hitherto attended the schools, of Geneva. Before the day of my departure arrived, the first misfortune of my life occurred- an omen of my future misery. My mother attended Elizabeth in an attack of scarlet fever. Elizabeth was saved, but my mother sickened and died. On her deathbed she joined the hands of Elizabeth and myself:- "My children," she said, "my firmest hopes of future happiness were placed on the prospect of your union. This expectation will now be the consolation of your father." The day of my departure for Ingolstadt, deferred for some weeks by my mother's death, at length arrived. I reached the town after a long and fatiguing journey, delivered my letters of introduction, and paid a visit to some of the principal professors. M. Krempe, professor of Natural Philosophy, was an uncouth man. He asked me several questions concerning my progress in different branches of science, and informed me I must begin my studies entirely anew. M. Waldman was very unlike his colleague. His voice was the sweetest I had ever heard. Partly from curiosity, and partly from idleness, I entered his lecture room, and his panegyric upon modern chemistry I shall never forget:-"The ancient teachers of this science," said he, "promised impossibilities, and performed nothing. The modern masters promise very little, and have, indeed, performed miracles. They have discovered how the blood circulates, and the nature of the air we breathe. They have acquired new and almost unlimited powers; they can command the thunders of the heaven, mimic the earthquake, and even mock the invisible world with its own shadows." Such were the professor's words, words of fate enounced to destroy me. As he went on, I felt as if my soul were grappling with a palpable enemy. So much has been done, exclaimed the soul of Frankenstein. More, far more, will I achieve: I will pioneer a new way, explore unknown powers, and unfold to the world the deepest mysteries of creation. I closed not my eyes that night; and from this time natural philosophy, and particularly chemistry, became nearly my sole occupation. My progress was rapid, and at the end of two years I made some discoveries in the improvement of chemical instruments which procured me great esteem at the University. I became acquainted with the science of anatomy, and often asked myself, Whence did the principle of life proceed? I observed the natural decay of the human body, and saw how the fine form of man was degraded and wasted. I examined and analysed all the minutiae of causation in the change from life to death and death to life, until from the midst of this darkness a sudden light broke in upon me. I became dizzy with the immensity of the prospect, and surprised that among so many men of genius I alone should be reserved to discover so astonishing a secret. When I found so astonishing a power placed within my hands, I hesitated a long time concerning the manner in which I should employ it. Although I possessed the capacity of bestowing animation, yet to prepare a frame for the reception of it, with all its intricacies of fibres, muscles, and veins, still remained a work of inconceivable difficulty and labour. I doubted at first whether I should attempt the creation of a being like myself, or one of simpler organization; but my imagination was too much exalted by my first success to permit me to doubt of my ability to give life to an animal as complex and wonderful as man. I collected bones from charnel houses, and the dissecting room and the slaughter house furnished many of my materials. Often my nature turned with loathing from my occupation, but the thought that if I could bestow animation upon lifeless matter I might in process of time renew life where death had apparently devoted the body to corruption, supported my spirits. In a solitary chamber at the top of the house I kept my workshop of filthy creation. The summer months passed, but my eyes were insensible to the charms of nature. Winter, spring, and summer passed away before my work drew to a close, but now every day showed me how well I had succeeded. But I had become a wreck, so engrossing was my occupation, and nervous to a most painful degree. I shunned my fellow-creatures as if I had been guilty of a crime. Frankenstein's Creation It was on a dreary night of November that I beheld the accomplishment of my toil. With an anxiety that amounted to agony, I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet. I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard; and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs. How can I delineate the wretch whom with such infinite pains and care I had endeavoured to form? His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but his watery eyes seemed almost of the same colour as the dun-white sockets in which they were set. I had worked hard for nearly two years for the sole purpose of infusing life into an inanimate body. For this I had deprived myself of rest and health. But now that I had finished, breathless horror and disgust filled my heart. Unable to endure the aspect of the being I had created, I rushed out of the room. I tried to sleep, but disturbed by the wildest dreams, I started up. By the dim and yellow light of the moon I beheld the miserable monster whom I had created. He held up the curtains of the bed, and his eyes were fixed on me. He might have spoken, but I did not hear; one hand was stretched out, seemingly to detain me, but I escaped and rushed downstairs. No mortal could support the horror of that countenance. I had gazed on him while unfinished; he was ugly then, but when those muscles and joints were rendered capable of motion, no mummy could be so hideous. I took refuge in the court-yard, and passed the night wretchedly. For several months I was confined by a nervous fever, and on my recovery was filled with a violent antipathy even to the name of Natural Philosophy. A letter from my father telling me that my youngest brother William had been found murdered, and bidding me return and comfort Elizabeth, made me decide to hasten home. It was completely dark when I arrived in the environs of Geneva. The gates of the town were shut, and I was obliged to pass the night at a village outside. A storm was raging on the mountains, and I wandered out to watch the tempest and resolved to visit the spot where my poor William had been murdered. Suddenly I perceived in the gloom a figure which stole from behind a clump of trees near me; I could not be mistaken. A flash of lightning illuminated the object, and discovered its shape plainly to me. Its gigantic stature, and the deformity of its aspect, more hideous than belongs to humanity, instantly informed me that it was the wretch to whom I had given life. What did he there? Could he be the murderer of my brother? No sooner did that idea cross my imagination than I became convinced of its truth. The figure passed me quickly, and I lost it in the gloom. I thought of pursuing, but it would have been in vain, for another flash discovered him to me hanging among the rocks, and he soon reached the summit and disappeared. It was about five in the morning when I entered my father's house. It was a house of mourning, and from that time I lived in daily fear lest the monster I had created should perpetrate some new wickedness. I wished to see him again that I might avenge the death of William. My wish was soon gratified. I had wandered off alone up the valley of Chamounix, and was resting on the side of the mountain, when I beheld the figure of a man advancing towards me, over the crevices in the ice, with superhuman speed. He approached: his countenance bespoke bitter anguish-it was the wretch whom I had created. "Devil," I exclaimed, "do you dare approach me? Begone, vile insect! Or, rather, stay, that I may trample you to dust!" "I expected this reception," said the monster. "All men hate the wretched: how, then, must I be hated, who am miserable beyond all living things. You purpose to kill me. Do your duty towards me and I will do mine towards you and the rest of mankind. If you will comply with my conditions I will leave them and you at peace; but if you refuse, I will glut the maw of death with the blood of your remaining friends." My rage was without bounds, but he easily eluded me and said: "Have I not suffered enough, that you seek to increase my misery? Remember that I am thy creature. Everywhere I see bliss, from which I alone am excluded. I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. I have assisted the labours of man, I have saved human beings from destruction, and I have been stoned and shot at as a recompense. The feelings of kindness and gentleness have given place to rage. Mankind spurns and hates me. The desert mountains and dreary glaciers are my refuge, and the bleak sky is kinder to me than your fellow-beings. Shall I not hate them who abhor me? Listen to me, Frankenstein. I have wandered through these mountains consumed by a burning passion which you alone can gratify. You must create a female for me with whom I can live. I am alone and miserable; man will not associate with me; but one as deformed and horrible as myself would not deny herself to me. "What I ask of you is reasonable and moderate. It is true, we shall be monstrous, cut off from all the world: but on that account we shall be more attached to one another. Our lives will not be happy, but they will be harmless, and free from the misery I now feel. If you consent, neither you nor any other human being shall ever see us again: I will go to the vast wilds of South America. We shall make our bed of dried leaves; the sun will shine on us as on man, and will ripen our foods. My evil passion will have fled, for I shall meet with sympathy. My life will flow quietly away, and in my dying moments I shall not curse my maker." His words had a strange effect on me. I compassionated him, and concluded that the justest view both to him and my fellow-creatures demanded of me that I should comply with his request. "I consent to your demand," I said, "on your solemn oath to quit Europe forever." "I swear," he cried, "by the sun and by the fire of love which burns in my heart that if you grant my prayer, while they exist you shall never behold me again. Depart to your home, and commence your labours: I shall watch their progress with unutterable anxiety." Saying this, he suddenly quitted me, fearful, perhaps, of any change in my sentiments. The Doom of Frankenstein I travelled to England with my friend Henry Clerval, and we parted in Scotland. I had fixed on one of the remotest of the Orkneys as the scene of my labours. Three years before I was engaged in the same manner, and had created a fiend whose barbarity had desolated my heart. I was now about to form another being, of whose dispositions I was alike ignorant. He had sworn to quit the neighbourhood of man, and hide himself in deserts, but she had not. They might even hate each other, and she might quit him. Even if they were to leave Europe, a race of devils would be propagated upon the earth, who might make the very existence of man precarious and full of terror. I was alone on a solitary island, when looking up, the monster whom I dreaded appeared. My mind was made up: I would never create another like to him. "Begone," I cried, "I break my promise. Never will I create your equal in deformity and wickedness. Leave me; I am inexorable." The monster saw my determination in my face, and gnashed his teeth in anger. "Shall each man," cried he, "find a wife for his bosom, and each beast have his mate, and I be alone? I had feelings of affection, and they were requited by detestation and scorn. Are you to be happy, while I grovel in the intensity of my wretchedness? I go, but remember, I shall be with you on your wedding night." I started forward, but he quitted the house with precipitation. In a few moments I saw him in his boat, which shot across the waters with an arrowy swiftness. The next day I set off to rejoin Clerval, and return home. But I never saw my friend again. The monster murdered him, and for a time I lay in prison on suspicion of the crime. On my release one duty remained to me. It was necessary that I should hasten without delay to Geneva, there to watch over the lives of those I loved, and to lie in wait for the murderer. Soon after my arrival, my father spoke of my long-contemplated marriage with Elizabeth. I remembered the fiend's words, "I shall be with you on your wedding night," and if I had thought what might be the devilish intention of my adversary I would never have consented. But thinking it was only my own death I was preparing I agreed with a cheerful countenance. Elizabeth seemed happy, and I was tranquil. In the meantime I took every precaution, carrying pistols and dagger, lest the fiend should openly attack me. After the ceremony was performed, a large party assembled at my father's; it was agreed that Elizabeth and I should proceed immediately to the shores of Lake Como. That night we stopped at an inn. I reflected how fearful a combat, which I momentarily expected, would be to my wife, and earnestly entreated her to retire. She left me, and I walked up and down the passages of the house inspecting every corner that might afford a retreat to my adversary. Suddenly I heard a shrill and dreadful scream. It came from the room into which Elizabeth had retired. I rushed in. There, lifeless and inanimate, thrown across the bed, her head hanging down, and her pale and distorted features half covered with her hair, was the purest creature on earth, my love, my wife, so lately living, and so dear. And at the open window I saw a figure the most hideous and abhorred. A grin was on the face of the monster as with his fiendish finger he pointed towards the corpse. Drawing a pistol I fired; but he eluded me, and running with the swiftness of lightning, plunged into the lake. The report of the pistol brought a crowd into the room. I pointed to the spot where he had disappeared, and we followed the track with boats. Nets were cast, but in vain. On my return to Geneva, my father sank under the tidings I bore, for Elizabeth had been to him more than a daughter, and in a few days he died in my arms. Then I decided to tell my story to a criminal judge in the town, and beseech him to assert his whole authority for the apprehension of the murderer. This Genevan magistrate endeavoured to soothe me as a nurse does a child, and treated my tale as the effects of delirium. I broke from the house angry and disturbed, and soon quitted Geneva, hurried away by fury. Revenge has kept me alive; I dared not die and leave my adversary in being. For many months this has been my task. Guided by a slight clue, I followed the windings of the Rhone, but vainly. The blue Mediterranean appeared; and, by a strange chance, I saw the fiend hide himself in a vessel bound for the Black Sea. Amidst the wilds of Tartary and Russia, although he still evaded me, I have ever followed in his track. Sometimes the peasants informed me of his path; sometimes he himself left some mark to guide me. The snows descended on my head, and I saw the print of his huge step on the white plain. My life, as it passed thus, was indeed hateful to me, and it was during sleep alone that I could taste joy. As I still pursued my journey to the northward, the snows thickened and the cold increased in the degree almost too severe to support. I found the fiend had pursued his journey across the frost-bound sea in a direction that led to no land, and exchanging my land sledge for one fashioned for the Frozen Ocean I followed him. I cannot guess how many days have passed since then. I was about to sink under the accumulation of distress when you took me on board. But I had determined, if you were going southward, still to trust myself to the mercy of the seas rather than abandon my purpose-for my task is unfulfilled. Walton's Letter, continued A week has passed away while I have listened to the strangest tale that ever imagination formed. The only joy that Frankenstein can now know will be when he composes his shattered spirit to peace and death. September 12: I am returning to England. I have lost my hopes of utility and glory. September 9 the ice began to move, and we were in the most imminent peril. I had promised the sailors that should a passage open to the south, I would not continue my voyage, but would instantly direct my course southward. On the 11th a breeze sprung from the west, and the passage towards the south became perfectly free. Frankenstein bade me farewell when he heard my decision, and died pressing my hand. At midnight I heard the sound of a hoarse human voice in the cabin where the remains of Frankenstein were lying. I entered, and there, over the body, hung a form gigantic, but uncouth and distorted, and with a face of appalling hideousness. The monster uttered wild and incoherent self-reproaches. "He is dead who called me into being," he cried, "and the remembrance of us both will speedily vanish. Soon I shall die, and what I now feel be no longer felt." He sprang from the cabin window as he said this, upon the ice-raft which lay close to the vessel, and was borne away by the waves, and lost in darkness and distance. |