|

|

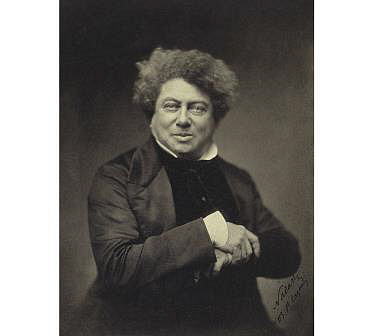

by Alexandre Dumas The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (Paris, 1823) Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870), known as Alexandre Dumas, père, is one of the most widely read and translated of all French authors. His historical romances have been adapted into at least 100 films, into plays and comic books. Abridged: JH/GH For more works by Alexandre Dumas, see The Index On Monday, August 18, 1572, a great festival was held in the palace of the Louvre. It was to celebrate the marriage of Henry of Navarre and Marguerite de Valois, a marriage that perplexed a good many people, and alarmed others. For Henry de Bourbon, King of Navarre, was the leader of the Huguenot party, and Marguerite was the daughter of Catherine de Medici, and the sister of the king, Charles IX., and this alliance between a Protestant and a Catholic, it seemed, was to end the strife that rent the nation. The king, too, had set his heart on this marriage, and the Huguenots were somewhat reassured by the king's declaration that Catholic and Huguenot alike were now his subjects, and were equally beloved by him. Still, there were many on both sides who feared and distrusted the alliance. At midnight, six days later, on August 24, the tocsin sounded, and the massacre of St. Bartholomew began. The marriage, indeed, was in no sense a love match; but Henry succeeded at once in making Marguerite his friend, for he was alive to the dangers that surrounded him. "Madame," he said, presenting himself at Marguerite's rooms on the night of the wedding festival, "whatever many persons may have said, I think our marriage is a good marriage. I stand well with you - you stand well with me. Therefore, we ought to act towards each other like good allies, since to-day we have been allied in the sight of God! Don't you think so?" "Without question, sir!" "I know, madame, that the ground at court is full of dangerous abysses; and I know that, though I am young and have never injured any person, I have many enemies. The king hates me, his brothers, the Duke of Anjou and the Duke D'Alençon, hate me. Catherine de Medici hated my mother too much not to hate me. Well, against these menaces, which must soon become attacks, I can only defend myself by your aid, for you are beloved by all those who hate me!" "I?" said Marguerite. "Yes, you!" replied Henry. "And if you will - I do not say love me - but if you will be my ally I can brave anything; while, if you become my enemy, I am lost." "Your enemy! Never, sir!" exclaimed Marguerite. "And my ally." "Most decidedly!" And Marguerite turned round and presented her hand to the king. "It is agreed," she said. "Political alliance, frank and loyal?" asked Henry. "Frank and loyal," was the answer. At the door Henry turned and said softly, "Thanks, Marguerite; thanks! You are a true daughter of France. Lacking your love, your friendship will not fail me. I rely on you, as you, for your part, may rely on me. Adieu, madame." He kissed his wife's hand; and then, with a quick step, the king went down the corridor to his own apartment. "I have more need of fidelity in politics than in love," he said to himself. If on both sides there was little attempt at fidelity in love, there was an honourable alliance, which was maintained unbroken and saved the life of Henry of Navarre from his enemies on more than one occasion. On the day of the St. Bartholomew massacre, while the Huguenots were being murdered throughout Paris, Charles IX., instigated by his mother, summoned Henry of Navarre to the royal armoury, and called upon him to turn Catholic or die. "Will you kill me, sire - me, your brother-in-law?" exclaimed Henry. Charles IX. turned away to the open window. "I must kill someone," he cried, and firing his arquebuse, struck a man who was passing. Then, animated by a murderous fury, Charles loaded and fired his arquebuse without stopping, shouting with joy when his aim was successful. "It's all over with me!" said Henry to himself. "When he sees no one else to kill, he will kill me!" Catherine de Medici entered as the king fired his last shot. "Is it done?" she said, anxiously. "No," the king exclaimed, throwing his arquebuse on the floor. "No; the obstinate blockhead will not consent!" Catherine gave a glance at Henry which Charles understood perfectly, and which said, "Why, then, is he alive?" "He lives," said the king, "because he is my relative." Henry felt that it was with Catherine he had to contend. "Madame," he said, addressing her, "I can see quite clearly that all this comes from you and not from brother-in-law Charles. It was you who planned this massacre to ensnare me into a trap which was to destroy us all. It was you who made your daughter the bait. It has been you who have separated me now from my wife, that she might not see me killed before her eyes!" "Yes; but that shall not be!" cried another voice; and Marguerite, breathless and impassioned, burst into the room. "Sir," said Marguerite to Henry, "your last words were an accusation, and were both right and wrong. They have made me the means for attempting to destroy you, but I was ignorant that in marrying me you were going to destruction. I myself owe my life to chance, for this very night they all but killed me in seeking you. Directly I knew of your danger I sought you. If you are exiled, sir, I will be exiled too; if they imprison you they shall imprison me also; if they kill you, I will also die!" She gave her hand to her husband and he seized it eagerly. "Brother," cried Marguerite to Charles IX., "remember, you made him my husband!" "Faith, Margot is right, and Henry is my brother-in-law," said the king. As time went on, if Catherine's hatred of Henry of Navarre did not diminish, Charles IX. certainly became more friendly. Catherine was for ever intriguing and plotting for the fortune of her sons and the downfall of her son-in-law, but Henry always managed to evade the webs she wove. At a certain boar-hunt Charles was indebted to Henry for his life. It was at the time when the king's brother D'Anjou had accepted the crown of Poland, and the second brother, D'Alençon, a weak-minded, ambitious man, was secretly hoping for a crown somewhere, that Henry paid his debt for the king's mercy to him on the night of St. Bartholomew. Charles was an intrepid hunter, but the boar had swerved as the king's spear was aimed at him, and, maddened with rage, the animal had rushed at him. Charles tried to draw his hunting-knife but the sheath was so tight it was impossible. "The boar! the boar!" shouted the king. "Help, D'Alençon, help!" D'Alençon was ghastly white as he placed his arquebuse to his shoulder and fired. The ball, instead of hitting the boar, felled the king's horse. "I think," D'Alençon murmured to himself, "that D'Anjou is King of France, and I King of Poland." The boar's tusk had indeed grazed the king's thigh when a hand in an iron glove dashed itself against the mouth of the beast, and a knife was plunged into its shoulder. Charles rose with difficulty, and seemed for a moment as if about to fall by the dead boar. Then he looked at Henry of Navarre, and for the first time in four-and-twenty years his heart was touched. "Thanks, Harry!" he said. "D'Alençon, for a first-rate marksman you made a most curious shot." On Marguerite coming up to congratulate the king and thank her husband, Charles added, "Margot, you may well thank him. But for him Henry III. would be King of France." "Alas, madame," returned Henry, "M. D'Anjou, who is always my enemy, will now hate me more than ever; but everyone has to do what he can." Had Charles IX. been killed, the Duke d'Anjou would have been King of France, and D'Alençon most probably King of Poland. Henry of Navarre would have gained nothing by this change of affairs. Instead of Charles IX. who tolerated him, he would have had the Duke d'Anjou on the throne, who, being absolutely at one with his mother, Catherine, had sworn his death, and would have kept his oath. These ideas were in his brain when the wild boar rushed on Charles, and like lightning he saw that his own existence was bound up with the life of Charles IX. But the king knew nothing of the spring and motive of the devotion which had saved his life, and on the following day he showed his gratitude to Henry by carrying him off from his apartments, and out of the Louvre. Catherine, in her fear lest Henry of Navarre should be some day King of France, had arranged the assassination of her son-in-law; and Charles, getting wind of this, warned him that the air of the Louvre was not good for him that night, and kept him in his company. Instead of Henry, it was one of his followers who was killed. Once more Catherine resolved to destroy Henry. The Huguenots had plotted with D'Alençon that he should be King of Navarre, since Henry not only abjured Protestantism but remained in Paris, being kept there indeed by the will of Charles IX. Catherine, aware of D'Alençon's scheme, assured her son that Henry was suffering from an incurable disease, and must be taken away from Paris when D'Alençon started for Navarre. "Are you sure that Henry will die?" asked D'Alençon. "The physician who gave me a certain book assured me of it." "And where is this book? What is it?" Catherine brought the book from her cabinet. "Here it is. It is a treatise on the art of rearing and training falcons by an Italian. Give it to Henry, who is going hawking with the king to-day, and will not fail to read it." "I dare not!" said D'Alençon, shuddering. "Nonsense!" replied Catherine. "It is a book like any other, only the leaves have a way of sticking together. Don't attempt to read it yourself, for you will have to wet the finger in turning over each leaf, which takes up so much time." "Oh," said D'Alençon, "Henry is with the court! Give me the book, and while he is away I will put it in his room." D'Alençon's hand was trembling as he took the book from the queen-mother, and with some hesitation and fear he entered Henry's apartment and placed the volume, open at the title-page. But it was not Henry, but Charles, seeking his brother-in-law, who found the book and carried it off to his own room. D'Alençon found the king reading. "By heavens, this is an admirable book!" cried Charles. "Only it seems as if they had stuck the leaves together on purpose to conceal the wonders it contains." D'Alençon's first thought was to snatch the book from his brother, but he hesitated. The king again moistened his finger and turned over a page. "Let me finish this chapter," he said, "and then tell me what you please. I have already read fifty pages." "He must have tasted the poison five-and-twenty times," thought D'Alençon. "He is a dead man!" The poison did its deadly work. Charles was taken ill while out hunting, and returned to find his dog dead, and in its mouth pieces of paper from the precious book on falconry. The king turned pale. The book was poisoned! Many things flashed across his memory, and he knew his life was doomed. Charles summoned Renè, a Florentine, the court perfumer to Catherine de Medici, to his presence, and bade him examine the dog. "Sire," said Renè, after a close investigation, "the dog has been poisoned by arsenic." "He has eaten a leaf of this book," said Charles; "and if you do not tell me whose book it is I will have your flesh torn from your bones by red-hot pincers." "Sire," stammered the Florentine, "this book belongs to me!" "And how did it leave your hands?" "Her majesty the queen-mother took it from my house." "Why did she do that?" "I believe she intended sending it to the King of Navarre, who had asked for a book on hawking." "Ah," said Charles, "I understand it all! The book was in Harry's room. It is destiny; I must yield to it. Tell me," he went on, turning to Renè, "this poison does not always kill at once?" "No, sire; but it kills surely. It is a matter of time." "Is there no remedy?" "None, sire, unless it be instantly administered." Charles compelled the wretched man to write in the fatal volume, "This book was given by me to the queen-mother, Catherine de Medici. - Renè," and then dismissed him. Henry, at his own prayer and for his personal safety, was confined in the prison of Vincennes by the king's order. Charles grew worse, and the physicians discussed his malady without daring to guess at the truth. Then Catherine came one day and explained to the king the cause of his disease. "Listen, my son; you believe in magic?" "Oh, fully," said Charles, repressing his smile of incredulity. "Well," continued Catherine, "all your sufferings proceed from magic. An enemy afraid to attack you openly has done so in secret; a terrible conspiracy has been directed against your majesty. You doubt it, perhaps, but I know it for a certainty." "I never doubt what you tell me," replied the king sarcastically. "I am curious to know how they have sought to kill me." "By magic. Look here." The queen drew from under her mantle a figure of yellow wax about ten inches high, wearing a robe covered with golden stars, and over this a royal mantle. "See, it has on its head a crown," said Catherine, "and there is a needle in its heart. Now do you recognise yourself?" "Myself?" "Yes, in your royal robes, with the crown on your head." "And who made this figure?" asked-the king, weary of the wretched farce. "The King of Navarre, of course!" "No, sire; he did not actually make it, but it was found in the rooms of M. de la Mole, who serves the King of Navarre." "So, then, the person who seeks to kill me is M. de la Mole?" said Charles. "He is only the instrument, and behind the instrument is the hand that directs it," replied Catherine. "This, then, is the cause of my illness. And now what must I do - for I know nothing of sorcery?" "The death of the conspirator destroys the charm. Its power ends with his life. You are convinced now, are you not, of the cause of your illness?" "Oh, certainly," Charles answered ironically. "And I am to punish M. de la Mole, as you say he is the guilty party?" "I say he is the instrument, and," muttered Catherine, "we have infallible means for making him confess the name of his principal." Catherine left hurriedly without understanding the sardonic laughter of the king, and as she went out Marguerite appeared. "Oh, sire - sire," cried Marguerite, "you know what she says is false. It is terrible to accuse anyone's own mother, but she only lives to persecute the man who is devoted to you, Henry - your Henry - and I swear to you that what she says is false!" "I think so, too, Margot. But Henry is safe. Safer in disgrace in Vincennes than in favour at the Louvre." "Oh, thanks, thanks! But there is another person in whose welfare I am interested, whom I hardly dare mention to my brother, much less to my king." "M. de la Mole, is it not? But do you know that a figure dressed in royal robes and pierced to the heart was found in his rooms?" "I know it; but it was the figure of a woman, not of a man." "And the needle?" "Was a charm not to kill a man, but to make a woman love him." "What was the name of this woman?" "Marguerite!" cried the queen, throwing herself down and bathing the king's hand in her tears. "Margot, what if I know the real author of the crime? For a crime has been committed, and I have not three months to live. I am poisoned, but it must be thought I die by magic." "You know who is guilty?" "Yes; but it must be kept from the world, and so it must be believed I die of magic, and by the agency of him they accuse." "But it is monstrous!" exclaimed Marguerite. "You know he is innocent. Pardon him - pardon him!" "I know it, but the world must believe him guilty. Let your friend die. His death alone can save the honour of our family. I am dying that the secret may be preserved." M. de la Mole, after enduring excruciating tortures at the hand of Catherine, without making any admissions, died on the scaffold. Before he died Charles showed Catherine the poisoned book, which he had kept under lock and key. "And now burn it, madame. I read this book too much, so fond was I of the chase. And the world must not know the weaknesses of kings. When it is burnt, please summon my brother Henry. I wish to speak to him about the regency." Catherine brought Henry of Navarre to the king, and warned him that if he accepted the regency he was a dead man. Charles, however, though on his death-bed, declared Henry should be regent. "Madame," he said, addressing his mother, "if I had a son he would be king, and you would be regent. In your stead, did you decline, the King of Poland would be regent; and in his stead, D'Alençon. But I have no son, and therefore the throne belongs to D'Anjou, who is absent. To make D'Alençon regent is to invite civil war. I have therefore chosen the fittest person for regent Salute him, madame; salute him, D'Alençon. It is the King of Navarre!" "Never," cried Catherine, "shall my race yield to a foreign one! Never shall a Bourbon reign while a Valois lives!" She left the room, followed by D'Alençon. "Henry," said Charles, "after my death you will be great and powerful. D'Anjou will not leave Poland - they will not let him. D'Alençon is a traitor. You alone are capable of governing. It is not the regency only, but the throne I give you." A stream of blood choked his speech. "The fatal moment is come," said Henry. "Am I to reign, or to live?" "Live, sire!" a voice answered, and Renè appeared. "The queen has sent me to ruin you, but I have faith in your star. It is foretold that you shall be king. Do you know that the King of Poland will be here very soon? He has been summoned by the queen. A messenger has come from Warsaw. You shall be king, but not yet." "What shall I do, then?" "Fly instantly to where your friends wait for you." Henry stooped and kissed his brother's forehead, then disappeared down a secret passage, passed through the postern, and, springing on his horse, galloped off. "He flies! The King of Navarre flies!" cried the sentinels. "Fire on him! Fire!" said the queen. The sentinels levelled their pieces, but the king was out of reach. "He flies!" muttered D'Alençon. "I am king, then!" At the same moment the drawbridge was hastily lowered, and Henry d'Anjou galloped into the court, followed by four knights, crying, "France! France!" "My son!" cried Catherine joyfully. "Am I too late?" said D'Anjou. "No. You are just in time. Listen!" The captain of the king's guards appeared at the balcony of the king's apartment. He broke the wand he held in two places, and holding a piece in either hand, called out three times, "King Charles the Ninth is dead!" King Charles the Ninth is dead! King Charles the Ninth is dead!" "Charles the Ninth is dead!" said Catherine, crossing herself. "God save Henry the Third!" All repeated the cry. "I have conquered," said Catherine, "and the odious Bourbon shall not reign!" |