|

|

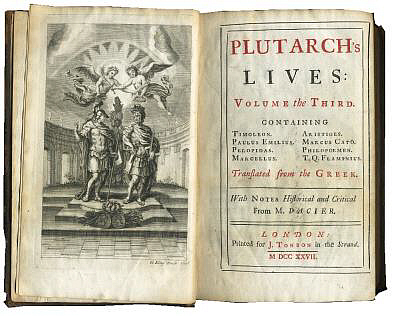

by Plutarch The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  An edition of 1727 (Caeronea, Greece, c80CE) Plutarch was a municipal administrator from Chærone in mainland Greece who wrote a considerable number of short biographies of which the most famous are these paralleling the lives of Greek and Roman worthies. Abridged: JH For more works by the Ancients, see The Index I. - Lycurgus and Numa According to the best authors, Lycurgus, the law-giver, reigned only for eight months as king of Sparta, until the widow of the late king, his brother, had given birth to a son, whom he named Charilaus. He then travelled for some years in Crete, Asia, and possibly also in Egypt, Libya, Spain, and India, studying governments and manners; and returning to Sparta, he set himself to alter the whole constitution of that kingdom, with the encouragement of the oracles and the favour of Charilaus. The first institution was a senate of twenty-eight members, whose place it was to strengthen the throne when the people encroached too far, and to support the people when the king should attempt to become absolute. Occasional popular assemblies, in the open air, were to be called, not to propose any subject of debate, but only to ratify or reject the proposals of the senate and the two kings. His second political enterprise was a new division of the lands, for he found a prodigious inequality, wealth being centred in the hands of a few; and by this reform Laconia became like an estate newly divided among many brothers. Each plot of land was sufficient to maintain a family in health, and they wanted nothing more. Then, desiring also to equalise property in movable objects, he resorted to the device of doing away with gold and silver currency, and establishing an iron coinage, of which great bulk and weight went to but little value. He excluded all unprofitable and superfluous arts; and the Spartans soon had no means of purchasing foreign wares, nor did any merchant ship unlade in their harbours. Luxury died away of itself, and the workmanship of their necessary and useful furniture rose to great excellence. Public tables were now established, where all must eat in common of the same frugal meal; whereby hardiness and health of body and mutual benevolence of mind were alike promoted. There were about fifteen to a table, to which each contributed in provisions or in money; the conversation was liberal and well-informed, and salted with pleasant raillery. Lycurgus left no law in writing; he depended on principles pervading the customs of the people; and he reduced the whole business of legislation into the bringing up of the young. And in this matter he began truly at the beginning, by regulating marriages. The man unmarried after the prescribed age was prosecuted and disgraced; and the father of four children was immune from taxation. Lycurgus considered the children as the property of the state rather than of the parents, and derided the vanity of other nations, who studied to have horses of the finest breed, yet had their children begotten by ordinary persons rather than by the best and healthiest men. At birth, the children were carried to be examined by the oldest men in council, who had the weaklings thrown away into a cavern, and gave orders for the education of the sturdy. As for learning, they had just what was necessary and no more, their education being directed chiefly to making them obedient, laborious, and warlike. They went barefoot, and for the most part naked. They were trained to steal with astuteness, to suffer pain and hunger, and to express themselves without an unnecessary word. Dignified poetry and music were encouraged. To the end of his life, the Spartan was kept ever in mind that he was born, not for himself, but for his country; the city was like one great camp, where each had his stated allowance and his stated public charge. Let us turn now to Numa Pompilius, the great law-giver of the Romans. A Sabine of illustrious virtue and great simplicity of life, he was elected to be king after the interregnum which followed on the disappearance of Romulus. He had spent much time in solitary wanderings in the sacred groves and other retired places; and there, it is reported, the goddess Egeria communicated to him a happiness and knowledge more than mortal. Numa was in his fortieth year, and was not easily persuaded to undertake the Roman kingdom. But his disinclination was overcome, and he was received with loud acclamations as the most pious of men and most beloved of the gods. His first act was to discharge the body-guard provided for him, and to appoint a priest for the cult of Romulus. But his great task was to soften the Romans, as iron is softened by fire, and to bring them from a violent and warlike disposition to a juster and more gentle temper. For Rome was composed at first of most hardy and resolute men, inveterate warriors. To reduce this people to mildness and peace, he called in the assistance of religion. By sacrifices, solemn dances, and processions, wherein he himself officiated, he mixed the charms of festal pleasure with holy ritual. He founded the hierarchy of priests, the vestal virgins, and several other sacred orders; and passed most of his time in performing some religious function or in conversing with the priests on some divine subject. And by all this discipline the people became so tractable, and were so impressed with Numa's power, that they would believe the most fabulous tales, and thought nothing impossible which he undertook. Numa further introduced agriculture, and fostered it as an incentive to peace; he distributed the citizens of Rome into guilds, or companies, according to their several arts and trades; he reformed the calendar, and did many other services to his people. Comparing, now, Lycurgus and Numa, we find that their resemblances are obvious - their wisdom, piety, talent for government, and their deriving their laws from a divine source. Of their distinctions, the chief is that Numa accepted, but Lycurgus relinquished, a crown; and as it was an honour to the former to attain royal dignity by his justice, so it was an honour to the latter to prefer justice to that dignity. Again, Lycurgus tuned up the strings of Sparta, which he found relaxed with luxury, to a keener pitch; Numa, on the contrary, softened the high and harsh tone of Rome. Both were equally studious to lead their people to sobriety, but Lycurgus was more attached to fortitude and Numa to justice. Though Numa put an end to the gain of rapine, he made no provision against the accumulation of great fortunes, nor against poverty, which then began to spread within the city. He ought rather to have watched against these dangers, for they gave birth to the many troubles that befell the Roman state. II. - Aristides and Cato Aristides had a close friendship with Clisthenes, who established popular government in Athens after the expulsion of the tyrants; yet he had at the same time a great veneration for Lycurgus of Sparta, whom he regarded as supreme among law-givers; and this led him to be a supporter of aristocracy, in which he was always opposed by Themistocles, the democrat. The latter was insinuating, daring, artful, and impetuous, but Aristides was solid and steady, inflexibly just, and incapable of flattery or deceit. Neither elated by honour nor disheartened by ill success, Aristides became deeply founded in the estimation of the best citizens. He was appointed public treasurer, and showed up the peculations of Themistocles and of others who had preceded him. When the fleet of Darius was at Marathon, with a view to subjugating Greece, Miltiades and Aristides were the Greek generals, who by custom were to command by turns, day about; and Aristides freely gave up his command to the other, to promote unity of discipline, and to give example of military obedience. The next year he became archon. Though a poor man and a commoner, Aristides won the royal and divine title of "the Just." At first loved and respected for his surname "the Just," Aristides came to be envied and dreaded for so extraordinary an honour, and the citizens assembled from all the towns in Attica and banished him by ostracism, cloaking their envy of his character under the pretence of guarding against tyranny. Three years later they reversed this decree, fearing lest Aristides should join the cause of Xerxes. They little knew the man; even before his recall he had been inciting the Greeks to defend their liberty. In the great battle of Platæa, Aristides was in command of the Athenians; Pausanias, commander-in-chief of all the confederates, joined him there with the Spartans. The opposing Persian army covered an immense area. In the engagements which took place the Greeks behaved with the utmost firmness, and at last stormed the Persian camp, with a prodigious slaughter of the enemy. When, later, Aristides was entrusted with the task of assessing the cities of the allies for a tax towards the war, and was thus clothed with an authority which made him master of Greece, though he set out poor he returned yet poorer, having arranged the burden with equal justice and humanity. In fact, he esteemed his poverty no less a glory than all the laurels he had won. The Roman counterpart of Aristides was Cato; which name he received for his wisdom, for Romans call wise men Catos. Marcus Cato, the censor, came of an obscure family, yet his father and grandfather were excellent soldiers. He lived on an estate which his father left him near the Sabine country. With red hair and grey eyes, his appearance was such, says an epigram, as to scare the spirits of the departed. Inured to labour and temperance, he had the sound constitution of one brought up in camps; and he had practised eloquence as a necessary instrument for one who would mix with affairs. While still a lad he had fought in so many battles that his breast was covered with scars; and all who spoke with him noted a gravity of behaviour and a dignity of sentiment such as to fit him for high responsibilities. A powerful nobleman, Valerius Flaccus, whose estate was near Cato's home, heard his servants praise their neighbour's laborious life. He sent for Cato, and, charmed with his sweet temper and ready wit, persuaded him to go to Rome and apply himself to political affairs. His rise was rapid; he became tribune of the soldiers, then quæstor, and at last was the colleague of Valerius both as consul and as censor. Cato's eloquence brought him the epithet of the Roman Demosthenes, but he was even more celebrated for his manner of living. Few were willing to imitate him in the ancient custom of tilling the ground with his own hands, in eating a dinner prepared without fire, and a spare, frugal supper; few thought it more honourable not to want superfluities than to possess them. By reason of its vast dominions, the commonwealth had lost its pristine purity and integrity; the citizens were frightened at labour and enervated by pleasure. But Cato never wore a costly garment nor partook of an elaborate meal; even when consul he drank the same wine as his servants. He thought nothing cheap that is superfluous. Some called him mean and narrow, others thought that he was setting an object-lesson to the growing luxury of the age. For my part, I think that his custom of using his servants like beasts of burden, and of turning them off or selling them when grown old, was the mark of an ungenerous spirit, which thinks that the sole tie between man and man is interest or necessity. For my own part, I would not sell even an old ox that had laboured for me. However that may be, his temperance was wonderful. When governor of Sardinia, where his predecessors had put the province to great expense, he did not even use a carriage, but walked from town to town with one attendant. He was inexorable in everything that concerned public justice. He proved himself a brave general in the field; and when he became censor, which was the highest dignity of the republic, he waged an uncompromising campaign against luxury, by means of an almost prohibitive tax on the expenditure of ostentatious superfluity. His style in speaking was at once humorous, familiar, and forcible, and many of his wise and pregnant sayings are remembered. When we compare Aristides and Cato, we are at once struck by many resemblances; and examining the several parts of their lives distinctly, as we examine a poem or a picture, we find that they both rose to great honour without the help of family connections, and merely by their own virtue and abilities. Both of them were equally victorious in war; but in politics Aristides was less successful, being banished by the faction of Themistocles; while Cato, though his antagonists were the most powerful men in Rome, kept his footing to the end like a skilled wrestler. Again, Cato was no less attentive to the management of his domestic affairs than he was to affairs of state, and not only increased his own fortune, but became a guide to others in finance and in agriculture. But Aristides, by his indigence, brought disgrace upon justice itself, as if it were the ruin and impoverishment of families; it is even said that he left not enough for the portions of his daughters nor for the expenses of his own funeral. So Cato's family produced prætors and consuls to the fourth generation; but of the descendants of Aristides some were conjurors and paupers, and not one of them had a sentiment worthy of his illustrious ancestor. III. - Demosthenes and Cicero That these two great orators were originally formed by nature in the same mould is shown by the similarity of their dispositions. They had the same ambition, the same love of liberty, and the same timidity in war and danger. Their fortunes also were similar; both raised themselves from obscure beginnings to authority and power; both opposed kings and tyrants; both of them were banished, then returned with honour, were forced to fly again, and were taken by their enemies; and with both of them expired the liberties of their countries. Demosthenes, while a weakly child of seven years, lost his father, and his fortune was dissipated by unworthy guardians. But his ambition was fired in early years by hearing the pleadings of the orator Callistratus, and by noting the honours which attended success in that profession. He at once applied himself to the practice of declamation, and studied rhetoric under Isæus; and as soon as he came of age he appeared at the Bar in the prosecution of his guardians for their embezzlements. Though successful in this claim, Demosthenes had much to learn, and his earlier speeches provoked the amusement of his audience. His manner was at once violent and confused, his voice weak and stammering, and his delivery breathless; but these faults were overcome by an arduous and protracted course of exercise in the subterraneous study which he had built, where he would remain for two or three months together. He corrected the stammering by speaking with pebbles in his mouth; strengthened his voice by running uphill and declaiming while still unbreathed; and his attitude and gestures were studied before a mirror. Demosthenes was rarely heard to speak extempore, and though the people called upon him in the assembly, he would sit silent unless he had come prepared. He wrote a great part, if not the whole, of each oration beforehand, so that it was objected that his arguments "smelled of the lamp"; yet, on exceptional occasions, he would speak unprepared, and then as if from a supernatural impulse. His nature was vindictive and his resentment implacable. He was never a time-server in word or in action, and he maintained to the end the political standpoint with which he had begun. The glorious object of his ambition was the defence of the cause of Greece against Philip; and most of his orations, including these Philippics, are written upon the principle that the right and worthy course is to be chosen for its own sake. He does not exhort his countrymen to that which is most agreeable, or easy, or advantageous, but to that which is most honourable. If, besides this noble ambition of his and the lofty tone of his orations, he had been gifted also with warlike courage and had kept his hands clean from bribes, Demosthenes would have deserved to be numbered with Cimon, Thucydides, and Pericles. Cicero's wonderful genius came to light even in his school-days; he had the capacity and inclination to learn all the arts, but was most inclined to poetry, and the time came when he was reputed the best poet as well as the greatest orator in Rome. After a training in law and some experience of the wars, he retired to a life of philosophic study, but being persuaded to appear in the courts for Roscius, who was unjustly charged with the murder of his father, Cicero immediately made his reputation as an orator. His health was weak; he could eat but little, and that only late in the day; his voice was harsh, loud, and ill regulated; but, like Demosthenes, he was able by assiduous practice to modulate his enunciation to a full, sonorous, and sweet tone, and his studies under the leading rhetoricians of Greece and Asia perfected his eloquence. His diligence, justice, and moderation were evidenced by his conduct in public offices, as quæstor, prætor, and then as consul. In his attack on Catiline's conspiracy, he showed the Romans what charms eloquence can add to truth, and that justice is invincible when properly supported. But his immoderate love of praise interrupted his best designs, and he made himself obnoxious to many by continually magnifying himself. Demosthenes, by concentrating all his powers on the single art of speaking, became unrivalled in the power, grandeur, and accuracy of his eloquence. Cicero's studies had a wider range; he strove to excel not only as an orator, but as a philosopher and a scholar also. Their difference of temperament is reflected in their styles. Demosthenes is always grave and serious, an austere man of thought; Cicero, on the other hand, loves his jest, and is sometimes playful to the point of buffoonery. The Greek orator never touches upon his own praise except with some great point in view, and then does it modestly and without offence; the Roman does not seek to hide his intemperate vanity. Both of these men had high political abilities; but while the former held no public office, and lies under the suspicion of having at times sold his talent to the highest bidder, the latter ruled provinces as a pro-consul at a time when avarice reigned unbridled, and became known only for his humanity and his contempt of money. |