|

|

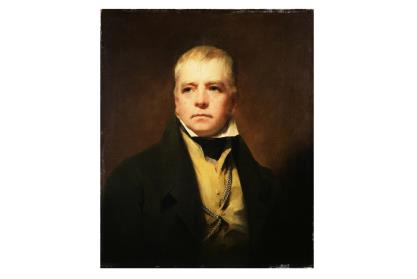

by Walter Scott The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (1817) Walter Scott (1771-1832) was a law-clerk and judge, Clerk of Session and Sheriff-Depute of Selkirkshire, one of the leading figures of Scottish Toryism and of the Highland Society. Scott was the first English-language author to achieve international fame, largely with novels of a romantic past. Abridged: JH For more works by Walter Scott, see The Index I. - I Meet Diana Vernon Early in the eighteenth century, when I, Frank Osbaldistone, was a youth of twenty, I was hastily summoned from Bordeaux, where, in a mercantile house, I was, as my father trusted, being initiated into the mysteries of commerce. As a matter of fact, my principal attention had been dedicated to literature and manly exercises. In an evil hour, my father had received my letter, containing my eloquent and detailed apology for declining a place in the firm, and I was summoned home in all haste, his chief ambition being that I should succeed, not merely to his fortune, but to the views and plans by which he imagined he could extend and perpetuate that wealthy inheritance. I did not understand how deeply my father's happiness was involved, and with something of his own pertinacity, had formed a determination precisely contrary, not conceiving that I should increase my own happiness by augmenting a fortune which I believed already sufficient. My father cut the matter short; when he was my age, his father had turned him out, and settled his legal inheritance on his younger brother; and one of that brother's sons should take my place, if I crossed him any further. At the end of the month he gave me to think the matter over, I found myself on the road to York, on a reasonably good horse, with fifty guineas in my pocket, travelling, as it would seem, for the purpose of assisting in the adoption of a successor to myself in my father's house and favour; he having decided that I should pay a visit to my uncle, and stay at Osbaldistone Hall, till I should receive further instructions. There had been such unexpected ease in the way in which my father had slipt the knot usually esteemed the strongest that binds society together, and let me depart as a sort of outcast from his family, that strangely lessened my self-confidence. The Muse, too, - the very coquette that had led me into this wilderness - deserted me, and I should have been reduced to an uncomfortable state of dullness had it not been for the conversation of strangers who chanced to pass the same way. One poor man with whom I travelled a day and a half, and whose name was Morris, afforded me most amusement. He had upon his pillion a very small, but apparently a very weighty portmanteau, which he would never trust out of his immediate care; and all his conversation was of unfortunate travellers who had fallen among thieves. He wrought himself into a fever of apprehension by the progress of his own narratives, and occasionally eyed me with doubt and suspicion, too ludicrous to be offensive. I found amusement in alternately exciting and lulling to sleep the causeless fears of my timorous companion, who tried in vain to induce a Scotchman with whom we dined in Darlington to ride with him, because the landlord informed us "that for as peaceable a gentleman as Mr. Campbell was, he was, moreover, as bold as a lion - seven highwaymen had he defeated with his single arm, as he came from Whitson tryste." "Thou art deceived, friend Jonathan," said Campbell, interrupting him. "There were but barely two, and two cowardly loons as man could wish to meet withal." My companion made up to him, and taking him aside seemed to press his company upon him. Mr. Campbell disengaged himself not very ceremoniously, and coming up to me, observed, "Your friend, sir, is too communicative, considering the nature of his trust." I hastened to assure him that that gentleman was no friend of mine, and that I knew nothing of him or his business, and we separated for the night. Next day I parted company with my timid companion, turning more westerly in the direction of my uncle's seat. I had already had a distant view of Osbaldistone Hall, when my horse, tired as he was, pricked up his ears at the notes of a pack of hounds in full cry. The headmost hounds soon burst out of the coppice, followed by three or four riders with reckless haste, regardless of the broken and difficult nature of the ground. "My cousins," thought I, as they swept past me: but a vision interrupted my reflections. It was a young lady, the loveliness of whose very striking features was enhanced by the animation of the chase, whose horse made an irregular movement as she passed me, which served as an apology for me to ride close up to her, as if to her assistance. There was no cause for alarm, for she guided her horse with the most admirable address and presence of mind. One of the young men soon reappeared, waving the brush of the fox in triumph, and after a few words the lady rode back to me and inquired, as she could not persuade "this cultivated young gentleman" to do so, if I had heard anything of a friend of theirs, one Mr. Francis Osbaldistone. I was too happy to acknowledge myself to be the party enquired after, and she then presented to me, "as his politeness seemed still to be slumbering," my cousin, young Squire Thorncliff Osbaldistone, and "Die Vernon, who has also the honour to be your accomplished cousin's poor kinswoman." After shaking hands with me, he left us to help couple up the hounds, and Miss Vernon rode with me to Osbaldistone Hall, giving me, on the way, a description of its inmates, of whom, she said, the only conversible beings beside herself were the old priest and Rashleigh - Sir Hildebrand's youngest son. II. - Rashleigh's Villainy Rashleigh Osbaldistone was a striking contrast to his young brothers, all tall, stout, and comely, without pretence to accomplishment except their dexterity in field sports. He welcomed me with the air of a man of the world, and though his appearance was far from prepossessing, he was possessed of a voice the most soft, mellow, and rich I ever heard. He had been intended for a priest, but when my father's desire to have one of Sir Hildebrand's sons in his counting-house was known, he had been selected, as, indeed, the only one who could be considered at all suitable. The day after my arrival, Miss Vernon, as we were following the hounds, showed me in the distance the hills of Scotland, and told me I could be there in safety in two hours. To my dismay, she explained that my timorous fellow-traveller had been robbed of money and dispatches, and accused me. The magistrate had let my uncle know, and both he and Miss Vernon, considering it a merit to distress a Hanoverian government in every way, never doubted my guilt, and only showed the way of escape. On my indignant denial, Miss Vernon rode with me to the magistrate's, where we met Rashleigh, and after a hasty private talk with him, in which from earnest she became angry and flung away from him, saying, "I will have it so." Immediately after we heard his horse's hoofs in rapid motion; and very shortly afterwards Mr. Campbell, the very Scotchman we had met at Darlington, entered the Justice's room, and giving him a billet from the Duke of Argyll to certify that he, Mr. Robert Campbell, was a person of good fame and character, prevailed on the magistrate to discharge me, for he had been with my late fellow-traveller at the time of the robbery, and could swear that the robber was a very different person. Morris was apparently more terrified than ever, but agreed to all Mr. Campbell said, and left the house with him. Miss Vernon made me promise to ask no questions, and I only entreated her, if at any time my services could be useful to her, she would command them without hesitation. Before Rashleigh's departure, I had realised his real character, and wrote to Owen, my father's old clerk, to hint that he should keep a strict guard over my father's interests. Notwithstanding Miss Vernon had charged Rashleigh with perfidious conduct towards herself, they had several private interviews together, though their bearing did not seem cordial; and he and I took up distant ground, each disposed to avoid all pretext for collision. I began to think it strange I had received no letter either from my father or Owen, though I had now been several weeks at Osbaldistone Hall - where the mode of life was too uniform to admit of description. Diana Vernon and I enjoyed much of our time in our mutual studies; although my vanity early discovered that I had given her an additional reason for disliking the cloister, to which she was destined if she would not marry any of Sir Hildebrand's sons, I could not confide in our affection, which seemed completely subordinate to the mysteries of her singular situation. She would not permit her love to overpower her sense of duty or prudence, and one day proved this by advising me at once to return to London - my father was in Holland, she said, and if Rashleigh was allowed to manage his affairs long, he would be ruined. He would use my father's revenues as a means of putting in motion his own ambitious schemes. I seized her hand and pressed it to my lips - the world could never compensate for what I left behind me, if I left the Hall. "This is folly! This is madness!" she cried, and my eyes, following the direction of hers, I saw the tapestry shake, which covered the door of the secret passage to Rashleigh's apartment. Prudence, and the necessity of suppressing my passion and obeying Diana's reiterated command of "Leave me! leave me!" came in time to prevent any rash action. I left the apartment in a chaos of thoughts. Above all I was perplexed by the manner in which Miss Vernon had received my tender of affection, and the glance of fear rather than surprise with which she had watched the motion of the tapestry. I resolved to clear up the mystery, and that evening, at a time when I usually did not visit the library, I, hesitating a moment with my hand on the latch, heard a suppressed footstep within, opened the door, and found Miss Vernon alone. I had determined to seek a complete explanation, but found she refused it with indignant defiance, and avowed to my face the preference for a rival. And yet, when I was about to leave her for ever, it cost her but a change of look and tone to lead me back, her willing subject on her own hard terms, agreeing that we could be nothing to each other but friends now or henceforward. She then gave me a letter which she said might never have reached my hands if it had not fallen into hers. It was from my father's partner, Mr. Tresham, to tell me that Rashleigh had gone to Scotland some time since to take up bills granted by my father, and had not since been heard of, that Owen had been dispatched in search of him, and I was entreated to go after him, and assist to save my father's mercantile honour. Having read this, Diana left me for a moment, and returned with a sheet of paper folded like a letter, but without any address. "If I understand you rightly," she said, "the funds in Rashleigh's possession must be recovered by a certain day. Take this packet; do not open it till other means have failed; within ten days of the fated day you may break the seal, and you will find directions that may be useful to you. Adieu, Frank, we never meet more; but sometimes think of your friend Die Vernon." She extended her hand, but I clasped her to my bosom. She sighed and escaped to her own apartment, and I saw her no more. III. - In the Highlands I had not been a day in Glasgow before, in obedience to a mysterious summons, I met Mr. Campbell, and was by him guided to the prison where my poor old friend Owen was confined. On his arrival two days before, he had gone to one of my father's correspondents, trusting that they who heretofore could not do too much to deserve the patronage of their good friends in Crane Alley, would now give their counsel and assistance. They met this with a counter-demand of instant security against ultimate loss, and when this was refused as unjust to the other creditors of Osbaldistone & Tresham, they had thrown him into prison, as he had a small share in the firm. In the midst of our sorrowful explanation we were disturbed by a loud knocking at the outer door of the prison. The Highland turnkey, with as much delay as possible, undid the fastenings, my guide sprang up the stair, and into Owen's apartment. He cast his eyes around, and then said to me, "Lend me your pistols. Yet, no, I can do without them. Whatever you see, take no heed, and do not mix your hand in another man's feud. This gear's mine, and I must manage it as best I can. I have been as hard bested and worse than I am even now." As he spoke, he confronted the iron door, like a fine horse brought up to the leaping-bar. But instead of a guard with bayonets fixed, there entered a good-looking young woman, ushering in a short, stout, important person - a magistrate. "A bonny thing it is, and a beseeming, that I should be kept at the door half-an-hour, Captain Stanchells," said he, addressing the principal jailer, who now showed himself. "How's this? how's this? Strangers in the jail after lock-up hours! I must see into this. But, first, I must hae a crack with an auld acquaintance here. Mr. Owen, Mr. Owen, how's a' wi' you man?" "Pretty well in body, I thank you, Mr. Jarvie," drawled out poor Owen, "but sore afflicted in spirit." Mr. Jarvie was another correspondent of my father's whom Owen had had no great belief in, largely because of his great opinion of himself. He now showed himself kindly and sensible, and asked Owen to let him see some papers he mentioned. While examining them, he observed my mysterious guide make a slight movement, and said, "I say, look to the door, Stanchells; shut it, and keep watch on the outside." Mr. Jarvie soon showed himself master of what he had been considering, and saying he could not see how Mr. Owen could arrange his affairs if he were kept lying there, undertook to be his surety and to have him free by breakfast time. He then took the light from the servant-maid's hand, and advanced to my guide, who awaited his scrutiny with great calmness, seated on the table. "Eh! oh! ah!" exclaimed the Bailie. "My conscience! it's impossible! and yet, no! Conscience, it canna be. Ye robber! ye cateran! born devil that ye are - can this be you?" "E'en as ye see, Bailie," said he. "Ye are a dauring villain, Rob," answered the Bailie; "and ye will be hanged. But bluid's thicker than water. Whar's the gude thousand pounds Scots than I lent ye, man, and when am I to see it again?" "As to when you'll see it - why, just 'when the King enjoys his ain again,' as the auld sang says." "Worst of a', Robin," retorted the Bailie. "I mean ye disloyal traitor - worst of a'! Ye had better stick to your auld trade o' theft-boot and blackmail than ruining nations. And wha the deevil's this?" he continued, turning to me. Owen explained that I was young Mr. Frank Osbaldistone, the only child of the head of the house, and the Bailie, Nicol Jarvie, having undertaken Owen's release, took me home to sleep at his house. I was astonished that Mr. Campbell should appear to Mr. Jarvie as the head of a freebooting Highland clan, and dismayed to think that Diana's fate could be involved in that of desperadoes of this man's description. The packet which Diana Vernon had given me I had opened in the presence of the Highlander, for the ten days had elapsed, and a sealed letter had dropped out. This had at once been claimed by Mr. Campbell, or Rob MacGregor, as Mr. Jarvie called him, and the address showed that it had gone to its rightful owner. Before we parted, MacGregor bade me visit him in the Highlands, and I kept this appointment in company with the Bailie. Strange to say, in the Highlands I met Diana Vernon, escorted by a single horseman, and from her received papers which had been in Rashleigh's possession. There was fighting in the Highlands, and the Bailie and I were both more than once in peril of our lives. IV. - Rob Roy to the Rescue No sooner had we returned from our dangerous expedition than I sought out Owen. He was not alone - my father was with him. The first impulse was to preserve the dignity of his usual equanimity - "Francis, I am glad to see you." The next was to embrace me tenderly - "my dear, dear son!" When the tumult of our joy was over, I learnt that my father had arrived from Holland shortly after Owen had set off for Scotland. By his extensive resources, with funds enlarged and credit fortified, he easily put right what had befallen only, perhaps, through his absence, and set out for Scotland to exact justice from Rashleigh Osbaldistone. The full extent of my cousin Rashleigh's villainy I had yet to learn. In the rebellion of 1715, when in an ill-omened hour the standard of the Stuart was set up, to the ruin of many honourable families, Rashleigh, with more than another Jacobite agent, revealed the plot to the Government. My poor uncle, Sir Hildebrand, was easily persuaded to join the standard of the Stuarts, and was soon taken and lodged in Newgate. He died in prison, but before he died he spoke with great bitterness against Rashleigh, now his only surviving child, and declared that neither he nor his sons who had perished would have plunged into political intrigue but for that very member of his family who had been the first to desert them. By his will, Sir Hildebrand devised his estates at Osbaldistone Hall to me as his next heir, cutting off Rashleigh with a shilling. Rashleigh had yet one more card to play. The villain was aware that Diana's father, Sir Frederick Vernon, whose life had been forfeited for earlier Jacobite plots, lived in hiding at Osbaldistone Hall, and this had given him power over Miss Vernon. Some time after I had returned to my father's office, I decided to visit Osbaldistone and take possession. On my arrival, Diana met me in the dining hall with her father. "We are your suppliants, Mr. Osbaldistone," said the old knight; "we claim the refuge and protection of your roof till we can pursue a journey where dungeons and death gape for me at every step." "Surely," I articulated, "Miss Vernon cannot suppose me capable of betraying anyone, much less you?" But scarcely had they retired to rest that night, when Rashleigh arrived with officers of the law, and exhibited his warrant, not only against Frederick Vernon, an attainted traitor, but also against Diana Vernon, spinster, and Francis Osbaldistone, accused of connivance at treason. He provided a coach for his prisoners, but in the park a number of Highlanders had gathered. "Claymore!" cried the leader of the Highlanders, as the coach appeared, and a scuffle instantly commenced. The officers of the law, surprised at so sudden an attack, conceived themselves surrounded, and galloped off in different directions. Rashleigh fell, mortally wounded by the leader of the band, who the next instant was at the carriage door. It was Rob Roy, who handed out Miss Vernon, and assisted her father and me to alight. "Mr. Osbaldistone," he said, in a whisper, "you have nothing to fear; I must look after those who have. Your friends will soon be in safety. Farewell, and forget not the MacGregor." He whistled; his band gathered round him, and, hurrying Diana and her father along with him, they were almost instantly lost in the glades of the forest. The death of Rashleigh, who had threatened to challenge at law my right to Osbaldistone Hall, left me access to my inheritance without interference. It was at once admitted that the ridiculous charge of connivance at treason was got up by an unscrupulous attorney on an affidavit made with the sole purpose of favouring Rashleigh's views, and removing me from Osbaldistone Hall. I learnt subsequently that the opportune appearance of MacGregor and his party was not fortuitous. The Scottish nobles and gentry engaged in the insurrection of 1715 were particularly anxious to further the escape of Sir Frederick Vernon, who, as an old and trusted agent of the house of Stuart, was possessed of matter enough to have ruined half Scotland, and Rob Roy was the person whom they pitched upon to assist his escape. Once at large, they found horses prepared for them, and by MacGregor's knowledge of the country were conducted to the western sea-coast, and safely embarked for France. From the same source I also learnt that Sir Frederick could not long survive a lingering disease, and that his daughter was placed in a convent, although it was her father's wish she should take the veil only on her own inclination. When these news reached me, I frankly told the state of my affections to my father. After a little hesitation he broke out with "I little thought a son of mine should have been lord of Osbaldistone Manor, and far less that he should go to a French convent for a spouse. But so dutiful a daughter cannot but prove a good wife. You have worked at the desk to please me, Frank, it is but fair you should wive to please yourself." Long and happily I lived with Diana, and heavily I lamented her death. Rob Roy died in old age and by a peaceful death some time about 1733, and is still remembered in his country as the Robin Hood of Scotland. |