|

|

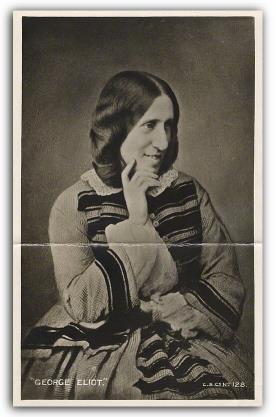

by 'George Eliot' (Mary Ann Evans) The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (1861) Mary Ann Evans ("George Eliot") was born Nov. 22, 1819, at South Farm, Arbury, Warwickshire, England, where her father was agent on the Newdigate estate. Mary established herself as one of the leading novelists of the Victorian era using the male pen name 'George Eliot', she said to ensure her works were taken seriously, but possibly also to shield her identity and hide her close relationship with the married George Henry Lewes. Abridged: JH/GH For more works by George Eliot, see The Index In the early years of the nineteenth century a linen-weaver named Silas Marner worked at his vocation in a stone cottage that stood among the nutty hedgerows near the village of Raveloe, and not far from the edge of a deserted stone-pit. It was fifteen years since Silas Marner had first come to Raveloe; he was then simply a pallid young man with prominent, short-sighted brown eyes. To the villagers among whom he had come to settle he seemed to have mysterious peculiarities, chiefly owing to his advent from an unknown region called "North'ard." He invited no comer to step across his door-sill, and he never strolled into the village to drink a pint at the Rainbow, or to gossip at the wheel-wrights'; he sought no man or woman, save for the purposes of his calling, or in order to supply himself with necessaries. At the end of fifteen years the Raveloe men said just the same things about Silas Marner as at the beginning. There was only one important addition which the years had brought; it was that Master Marner had laid by a fine sight of money somewhere, and that he could buy up "bigger men than himself." But while his daily habits presented scarcely any visible change, Marner's inward life had been a history and a metamorphosis as that of every fervid nature must be when it has been condemned to solitude. His life, before he came to Raveloe, had been filled with the close fellowship of a narrow religious sect, where the poorest layman had the chance of distinguishing himself by gifts of speech; and Marner was highly thought of in that little hidden world, known to itself as the church assembling in Lantern Yard. He was believed to be a young man of exemplary life and ardent faith, and a peculiar interest had been centred in him ever since he had fallen at a prayer-meeting into a trance or cataleptic fit, which lasted for an hour. Among the members of his church there was one young man, named William Dane, with whom he lived in close friendship; and it seemed to the unsuspecting Silas that the friendship suffered no chill, even after he had formed a closer attachment, and had become engaged to a young servant-woman. At this time the senior deacon was taken dangerously ill, and Silas and William, with others of the brethren, took turns at night-watching. On the night the old man died, Silas fell into one of his trances, and when he awoke at four o'clock in the morning death had come, and, further, a little bag of money had been stolen from the deacon's bureau, and Silas's pocket-knife was found inside the bureau. For some time Silas was mute with astonishment, then he said, "God will clear me; I know nothing about the knife being there, or the money being gone. Search me and my dwelling." The search was made, and it ended in William Dane finding the deacon's bag, empty, tucked behind the chest of drawers in Silas's chamber. According to the principles of the church in Lantern Yard prosecution was forbidden to Christians. But the members were bound to take other measures for finding out the truth, and they resolved on praying and drawing lots; there was nothing unusual about such proceedings a hundred years ago. Silas knelt with his brethren, relying on his own innocence being certified by immediate Divine interference. The lots declared that Silas Marner was guilty. He was solemnly suspended from church-membership, and called upon to render up the stolen money; only on confession and repentance could he be received once more within the fold of the church. Marner listened in silence. At last, when everyone rose to depart, he went towards William Dane and said, in a voice shaken by agitation, "The last time I remember using my knife was when I took it out to cut a strap for you. I don't remember putting it in my pocket again. You stole the money, and you have woven a plot to lay the sin at my door. But you may prosper for all that; there is no just God, but a God of lies, that bears witness against the innocent!" There was a general shudder at this blasphemy. Poor Marner went out with that despair in his soul - that shaken trust in God and man which is little short of madness to a loving nature. In the bitterness of his wounded spirit, he said to himself, "She will cast me off, too!" and for a whole day he sat alone, stunned by despair. The second day he took refuge from benumbing unbelief by getting into his loom and working away as usual, and, before many hours were past, the minister and one of the deacons came to him with a message from Sarah, the young woman to whom he had been engaged, that she held her engagement at an end. In little more than a month from that time Sarah was married to William Dane, and not long afterwards it was known to the brethren in Lantern Yard that Silas Marner had departed from the town. When Silas Marner first came to Raveloe he seemed to weave like a spider, from pure impulse, without reflection. Then there were the calls of hunger, and Silas, in his solitude, had to provide his own breakfast, dinner, and supper, to fetch his own water from the well, and put his own kettle on the fire; and all these immediate promptings helped to reduce his life to the unquestioning activity of a spinning insect. He hated the thought of the past; there was nothing that called out his love and fellowship towards the strangers he had come amongst; and the future was all dark, for there was no Unseen Love that cared for him. It was then, when all purpose of life was gone, that Silas got into the habit of looking towards the money he received for his weaving, and grasping it with a sense of fulfilled effort. Gradually, the guineas, the crowns, and the half-crowns, grew to a heap, and Marner drew less and less for his own wants, trying to solve the problem of keeping himself strong enough to work sixteen hours a day on as small an outlay as possible. He handled his coins, he counted them, till their form and colour were like the satisfaction of a thirst to him; but it was only in the night, when his work was done, that he drew them out, to enjoy their companionship. He had taken up some bricks in his floor underneath his loom, and here he had made a hole in which he set the iron pot that contained his guineas and silver coins, covering the bricks with sand whenever he replaced them. So, year after year, Silas Marner lived in this solitude, his guineas rising in the iron pot, and his life narrowing and hardening itself more and more as it became reduced to the functions of weaving and hoarding. This is the history of Silas Marner until the fifteenth year after he came to Raveloe. Then, about the Christmas of that year, a second great change came over his life. It was a raw, foggy night, with rain, and Silas was returning from the village, plodding along, with a sack thrown round his shoulders, and with a horn lantern in his hand. His legs were weary, but his mind was at ease with the sense of security that springs from habit. Supper was his favourite meal, because it was his time of revelry, when his heart warmed over his gold. He reached his door in much satisfaction that his errand was done; he opened it, and to his short-sighted eyes everything remained as he had left it, except that the fire sent out a welcome increase of heat. As soon as he was warm he began to think it would be a long while to wait till after supper before he drew out his guineas, and it would be pleasant to see them on the table before him as he ate his food. He rose and placed his candle unsuspectingly on the floor near his loom, swept away the sand, without noticing any change, and removed the bricks. The sight of the empty hole made his heart leap violently, but the belief that his gold was gone could not come at once - only terror, and the eager effort to put an end to the terror. He passed his trembling hand all about the hole, then he held the candle and examined it curiously, trembling more and more. He searched in every corner, he turned his bed over, and shook it, and kneaded it; he looked in his brick oven; and when there was no other place to be searched, he felt once more all round the hole. He could see every object in his cottage, and his gold was not there. He put his trembling hands to his head, and gave a wild, ringing scream - the cry of desolation. Then the idea of a thief began to present itself, and he entertained it eagerly, because a thief might be caught and made to restore the gold. The robber must be laid hold of. Marner's ideas of legal authority were confused, but he felt that he must go and proclaim his loss; and the great people in the village - the clergyman, the constable, and Squire Cass - would make the thief deliver up the stolen money. It was to the village inn Silas Marner went, where the parish clerk and a select company were assembled, and told the story of his loss - £272 12s. 6d. in all. The machinery of the law was set in motion, but no thief was ever captured, nor could grounds be found for suspicion against any persons. What had really happened was that Dunsey Cass, Squire Cass's second son - a mean, boastful rascal - on his way home on foot from hunting, saw the light in the weaver's cottage, and knocked, hoping to borrow a lantern, for the lane was unpleasantly slippery, and the night dark. But all was silence in the cottage, for the weaver at that moment had not yet reached home. For a minute Dunsey thought that old Marner might be dead, fallen over into the stone pits. And from that came the decision that he must be dead. If so, the question arose, what would become of the money that everybody said the old miser had put by? Dunstan Cass was in difficulties for want of money, and he had killed his brother's horse that day on the hunting-field. Who would know, if Marner was dead, that anybody had come to take his hoard of money away? There were only three hiding-places where he had heard of cottagers' hoards being found: the thatch, the bed, and a hole in the floor. His eyes travelling eagerly over the floor, noted a spot where the sand had been more carefully spread. Dunstan found the hole and the money, now hidden in two leathern bags. From their weight he judged they must be filled with guineas. Quickly he hastened out into the darkness with the bags, and Dunstan Cass was seen no more alive. At the very moment when he turned his back on the cottage Silas Marner was not more than a hundred yards away. It was New Year's Eve, and Squire Cass was giving a dance to the neighbouring gentry of Raveloe. There had been snow in the afternoon, but at seven o'clock it had ceased, and a freezing wind had sprung up. A woman, shabbily dressed, with a child in her arms, was making her way towards Raveloe, seeking the Red House, where Squire Cass lived. It was not the squire she wanted, but his eldest son, Godfrey, to whom she was secretly married. The marriage - the result of rash impulse - had been an unhappy one from the first, for Godfrey's wife was the slave of opium. The squire had long desired that his son should marry Miss Nancy Lammeter, and would have turned him out of house and home had he known of the unfortunate marriage already contracted. Cold and weariness drove the woman, even while she walked, to the only comfort she knew. She raised the black remnant to her lips, and then flung the empty phial away. Now she walked, always more and more drowsily, and clutched more and more automatically the sleeping child at her bosom. Soon she felt nothing but a supreme longing to lie down and sleep; and so sank down against a straggling furze-bush, an easy pillow enough; and the bed of snow, too, was soft. The cold was no longer felt, but her arms did not at once relax their instinctive clutch, and the little one slumbered on. The complete torpor came at last; the fingers lost their tension, the arms unbent; then the little head fell away from the bosom, and the blue eyes of the child opened wide on the cold starlight. At first there was a little peevish cry of "Mammy," as the child rolled downward; and then, suddenly, its eyes were caught by a bright gleaming light on the white ground, and with the ready transition of infancy it decided the light must be caught. In an instant the child had slipped on all fours, and, after making out that the cunning gleam came from a very bright place, the little one, rising on its legs, toddled through the snow - toddled on to the open door of Silas Marner's cottage, and right up to the warm hearth, where was a bright fire. The little one, accustomed to be left to itself for long hours without notice, squatted down on the old sack spread out before the fire, in perfect contentment. Presently the little golden head sank down, and the blue eyes were veiled by their delicate half-transparent lids. But where was Silas Marner while this strange visitor had come to his hearth? He was in the cottage, but he did not see the child. Since he had lost his money he had contracted the habit of opening his door, and looking out from time to time, as if he thought that his money might, somehow, be coming back to him. That morning he had been told by some of his neighbours that it was New Year's Eve, and that he must sit up and hear the old year rung out, and the new rung in, because that was good luck, and might bring his money back again. Perhaps this friendly Raveloe way of jesting had helped to throw Silas into a more than usually excited state. Certainly he opened his door again and again that night, and the last time, just as he put out his hand to close it, the invisible wand of catalepsy arrested him, and there he stood like a graven image, powerless to resist either the good or evil that might enter. When Marner's sensibility returned he was unaware of the break in his consciousness, and only noticed that he was chilled and faint. Turning towards the hearth it seemed to his blurred vision as if there was a heap of gold on the floor; but instead of hard coin his fingers encountered soft, warm curls. In utter amazement, Silas fell on his knees to examine the marvel: it was a sleeping child, a round, fair thing, with soft, yellow rings all over its head. Could this be the little sister come back to him in a dream - his little sister whom he had carried about in his arms for a year before she died? That was the first thought. Was it a dream? It was very much like his little sister. How and when had the child come in without his knowledge? But there was a cry on the hearth; the child had awakened, and Marner stooped to lift it on to his knee. He had plenty to do through the next hour. The porridge, sweetened with some dry brown sugar, stopped the cries of the little one for "mammy." Then it occurred to Silas's dull bachelor mind that the child wanted its wet boots off, and this having been done, the wet boots suggested that the child had been walking on the snow. He made out the marks of the little feet in the snow, and, holding the child in his arms, followed their track to the furze-bush. Then he became aware that there was something more than the bush before him - that there was a human body, half covered with the shifting snow. With the child in his arms, Silas at once went for the doctor, who was spending the evening at the Red House. And Godfrey Cass recognised that it was his own child he saw in Marner's arms. The woman was dead - had been dead for some hours, the doctor said; and Godfrey, who had accompanied him to Marner's cottage, understood that he was free to marry Nancy Lammeter. "You'll take the child to the parish to-morrow?" Godfrey asked, speaking as indifferently as he could. "Who says so?" said Marner sharply. "Will they make me take her? I shall keep her till anybody shows they've a right to take her away from me. The mother's dead, and I reckon it's got no father. It's a lone thing, and I'm a lone thing. My money's gone - I don't know where, and this is come from I don't know where." Godfrey returned to the Red House with a sense of relief and gladness, and Silas kept the child. There had been a softening of feeling to him in the village since the day of his robbery, and now an active sympathy was aroused amongst the women. The child was christened Hephzibah, after Marner's mother, and was called Eppie for short. Eppie had come to link Silas Marner once more with the whole world. The disposition to hoard had utterly gone, and there was no longer any repulsion around to him. As the child grew up, one person watched with keener, though more hidden, interest than any other the prosperous growth of Eppie under the weaver's care. The squire was dead, and Godfrey Cass was married to Nancy Lammeter. He had no child of his own save the one that knew him not. No Dunsey had ever turned up, and people had ceased to think of him. Sixteen years had passed, and now Aaron Winthrop, a well-behaved young gardener, is wanting to marry Eppie, and Eppie is willing to have him "some time." "'Everybody's married some time,' Aaron says," said Eppie. "But I told him that wasn't true, for I said look at father - he's never been married." "No, child," said Silas, "your father was a lone man till you was sent to him." "But you'll never be lone again, father," said Eppie tenderly. "That was what Aaron said - 'I could never think o' taking you away from Master Marner, Eppie.' And I said, 'It 'ud be no use if you did, Aaron.' And he wants us all to live together, so as you needn't work a bit, father, only what's for your own pleasure, and he'd be as good as a son to you - that was what he said." The proposal to separate Eppie from her foster-father came from Godfrey Cass. When the old stone-pit by Marner's cottage went dry, owing to drainage operations, the skeleton of Dunstan Cass was found, wedged between two great stones. The watch and seals were recognised, and all the weaver's money was at the bottom of the pit. The shock of this discovery moved Godfrey to tell Nancy the secret of his earlier marriage. "Everything comes to light, Nancy, sooner or later," he said. "That woman Marner found dead in the snow - Eppie's mother - was my wife. Eppie is my child. I oughtn't to have left the child unowned. I oughtn't to have kept it from you." "It's but little wrong to me, Godfrey," Nancy answered sadly. "You've made it up to me - you've been good to me for fifteen years. It'll be a different coming to us, now she's grown up." They were childless, and it hadn't occurred to them as they approached Silas Marner's cottage that Godfrey's offer might be declined. At first Godfrey explained that he and his wife wanted to adopt Eppie in place of a daughter. "Eppie, my child, speak," said old Marner faintly. "I won't stand in your way. Thank Mr. and Mrs. Cass." "Thank you, ma'am - thank you, sir," said Eppie dropping a curtsy; "but I can't leave my father, nor own anybody nearer than him." Godfrey Cass was irritated at this obstacle. "But I've a claim on you, Eppie," he returned. "It's my duty, Marner, to own Eppie as my child, and provide for her. She's my own child. Her mother was my wife. I've a natural claim on her." "Then, sir, why didn't you say so sixteen years ago, and claim her before I'd come to love her, i'stead o' coming to take her from me now, when you might as well take the heart out o' my body? When a man turns a blessing from his door, it falls to them as take it in. But let it be as you will. Speak to the child. I'll hinder nothing." "Eppie, my dear," said Godfrey, looking at his daughter not without some embarrassment, "it'll always be our wish that you should show your love and gratitude to one who's been a father to you so many years; but we hope you'll come to love us as well, and though I haven't been what a father should ha' been to you all these years, I wish to do the utmost in my power for you now, and provide for you as my only child. And you'll have the best of mothers in my wife." Eppie did not come forward and curtsy as she had done before, but she held Silas's hand in hers and grasped it firmly. "Thank you, ma'am - thank you, sir, for your offers - they're very great and far above my wish. For I should have no delight in life any more if I was forced to go away from my father." In vain Nancy expostulated mildly. "I can't feel as I've got any father but one," said Eppie. "I've always thought of a little home where he'd sit i' the corner, and I should fend and do everything for him. I can't think o' no other home. I wasn't brought up to be a lady, and," she ended passionately, "I'm promised to marry a working man, as'll live with father and help me to take care of him." Godfrey Cass and his wife went out. A year later Eppie was married, and Mrs. Godfrey Cass provided the wedding dress, and Mr. Cass made some necessary alterations to suit Silas's larger family. "Oh, father," said Eppie, when the bridal party returned from the church, "what a pretty home ours is! I think nobody could be happier than we are!" |