|

|

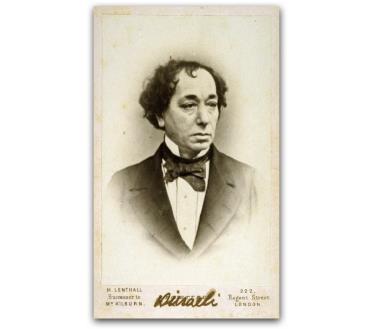

by Benjamin Disraeli The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (1845) Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield (December 21, 1804, - 1881) was not only a British Conservative Prime Minister, but also a novelist of significant powers. His books reflect his political views and remain important sources for the lives and opinions of the mid-nineteenth century. Abridged: JH For more works by Disraeli, see The Index I. - Hard Times for the Poor It was Derby Day, 1837. Charles Egremont was in the ring at Epsom with a band of young patricians. Groups surrounded the betting post, and the odds were shouted lustily by a host of horsemen. Egremont had backed Caravan to win, and Caravan lost by half a length. Charles Egremont was the younger brother of the Earl of Marney; he had received £15,000 on the death of his father, and had spent it. Disappointed in love at the age of twenty-four, Egremont left England, to return after eighteen months' absence a much wiser man. He was now conscious that he wanted an object, and, musing over action, was ignorant how to act. The morning after the Derby, Egremont, breakfasting with his mother, learnt that King William IV. was dying, and that a dissolution of parliament was at hand. Lady Marney was a great stateswoman, a leader in fashionable politics. "Charles," said Lady Marney, "you must stand for the old borough, for Marbury. No doubt the contest will be very expensive, but it will be a happy day for me to see you in parliament, and Marney will, of course, supply the funds. I shall write to him, and perhaps you will do so yourself." The election took place, and Egremont was returned. Then he paid a visit to his brother at Marney Abbey, and an old estrangement between the two was ended. Marney Abbey was as remarkable for its comfort and pleasantness of accommodation as for its ancient state and splendour. It had been a religious house. The founder of the Marney family, a confidential domestic of one of the favourites of Henry VIII., had contrived by unscrupulous zeal to obtain the grant of the abbey lands, and in the reign of Elizabeth came a peerage. The present Lord Marney upheld the workhouse, hated allotments and infant schools, and declared the labourers on his estate to be happy and contented with a wage of seven shillings a week. The burning of hayricks on the Abbey Farm at the time of Egremont's visit showed that the torch of the incendiary had been introduced and that a beacon had been kindled in the agitated neighbourhood. For misery lurked in the wretched tenements of the town of Marney, and fever was rife. The miserable hovels of the people had neither windows nor doors, and were unpaved, and looked as if they could scarcely hold together. There were few districts in the kingdom where the rate of wages was more depressed. "What do you think of this fire?" said Egremont to a labourer at the Abbey Farm. "I think 'tis hard times for the poor, sir," was the reply, given with a shake of the head. II. - The Old Tradition "Why was England not the same land as in the days of his light-hearted youth?" Charles Egremont mused, as he wandered among the ruins of the ancient abbey. "Why were these hard times for the poor?" Brooding over these questions, he observed two men hard by in the old cloister garden, one of lofty stature, nearer forty than fifty years of age, the other younger and shorter, with a pale face redeemed from ugliness by its intellectual brow. Egremont joined the strangers, and talked. "Our queen reigns over two nations, between whom there is no intercourse and no sympathy - the rich and the poor," said the younger stranger. As he spoke, from the lady chapel rose the evening hymn to the Virgin in tones of almost supernatural tenderness. The melody ceased; and Egremont beheld a female form, a countenance youthful, and of a beauty as rare as it was choice. The two men joined the beautiful maiden; and the three quitted the abbey grounds together without another word, and pursued their way to the railway station. "I have seen the tomb of the last abbot of Marney, and I marked your name on the stone, my father," said the maiden. "You must regain our lands for us, Stephen," she added to the younger man. "I can't understand why you lost sight of those papers, Walter," said Stephen Morley. "You see, friend, they were never in my possession; they were not mine when I saw them. They were my father's. He was a small yeoman, well-to-do in the world, but always hankering after the old tradition that the lands were ours. This Hatton got hold of him; he did his work well, I have heard. It is twenty-five years since my father brought his writ of right, and though baffled, he was not beaten. Then he died; his affairs were in great confusion; he had mortgaged his land for his writ. There were debts that could not be paid. I had no capital. I would not sink to be a labourer. I had heard much of the high wages of this new industry; I left the land." "And the papers?" "I never thought of them, or thought of them with disgust, as the cause of my ruin. Of Hatton, I have not heard since my father's death. He had quitted Mowbray, and none could give me tidings of him. When you came and showed me in a book that the last abbot of Marney was a Walter Gerard, the old feeling stirred again, and though I am but the overlooker at Mr. Trafford's mill, I could not help telling you that my fathers fought at Agincourt." They approached the station, entered the train, and two hours later arrived at Mowbray. Gerard and Morley left their companion at a convent gate in the suburbs of the manufacturing town. The two men made their way through the streets and entered a prominent public house. Here they sought an interview with the landlord, and from him got information of Hatton's brother. "You have heard of a place called Hell-house Yard?" said the publican. "Well, he lives there, and his name is Simon, and that's all I know about him." III. - The Gulf Impassable When it came to the point, Lord Marney very much objected to paying Egremont's election expenses, and proposed instead that he should accompany him to Mowbray Castle, and marry Earl Mowbray's daughter, Lady Joan Fitz-Warene. Lord Mowbray was the grandson of a waiter, who had gone out to India a gentleman's valet, and returned a nabob. Lord Mowbray's two daughters-he had no sons - were great heiresses. Lady Joan was doctrinal; Lady Maud inquisitive. Egremont fell in love with neither, and the visit was a failure. Lord Marney declined to pay the election expenses. The brothers parted in anger; and Egremont took up his abode in a cottage in Mowedale, a few miles outside the town of Mowbray. He was drawn to this by the knowledge that Walter Gerard and his daughter Sybil, and their friend Stephen Morley, lived close by. Of Egremont's rank these three were ignorant. Sybil had met him with Mr. St. Lys, the good vicar of Mowbray, relieving the misery of a poor weaver's family in the town, and at Mowedale he passed as Mr. Franklin, a journalist. For some weeks Egremont enjoyed the peace of rural life, and the intercourse with the Gerards ripened into friendship. When the time came for parting, for Egremont had to take his seat in parliament, it was a tender farewell on both sides. Egremont, embarrassed by his deception, could not only speak vaguely of their meeting again soon. The thought of parting from Sybil nearly overwhelmed him. When he met Gerard and Morley again it was in London, and disguise was no longer possible. Gerard and Morley came as delegates to the Chartist National Convention in 1839, and, deputed by their fellows to interview Charles Egremont, M.P., came face to face with "Mr. Franklin." The general misery in the country at that time was appalling. Weavers and miners were starving, agricultural labourers were driven into the new workhouses, and riots were of common occurrence. The Chartists believed their proposals would improve matters, other working-class leaders believed that a general stoppage of work would be more effective. Sybil, in London with her father, ardently supported the popular movement. Meeting Egremont near Westminster Abbey on the very day after Gerard and Morley had waited upon him, she allowed him to escort her home. Then, for the first time, she learnt that her friend "Mr. Franklin" was the brother of Lord Marney. It was in vain Egremont urged that they might still be friends, that the gulf between rich and poor was not impassable. "Oh, sir," said Sybil haughtily, "I am one of those who believe the gulf is impassable - yes, utterly impassable!" IV. - Plotting Against Lord De Mowbray Stephen Morley was the editor of the "Mowbray Phoenix," a teetotaler, a vegetarian, a believer in moral force. The friend of Gerard, and in love with Sybil, Stephen looked with no favour on Egremont. Although a delegate to the Chartist Convention, Stephen had not forgotten the claims of Gerard to landed estate, and had pursued his inquiries as to the whereabouts of Hatton with some success. First Stephen had journeyed to Woodgate, commonly known as Hell-house Yard, a wild and savage place, the abode of a lawless race of men who fashioned locks and instruments of iron. Here he had found Simon Hatton, who knew nothing of his brother's residence. By accident Stephen discovered that the man he sought lived in the Temple. Baptist Hatton at that time was the most famous of heraldic antiquaries. Not a pedigree in dispute, not a peerage in abeyance, but it was submitted to his consideration. A solitary man was Baptist Hatton, wealthy and absorbed in his pursuits. The meeting with Morley excited him, and he turned over the matter anxiously in his mind as he sat alone. "The son of Walter Gerard, a Chartist delegate! The best blood in England! Those infernal papers! They made my fortune; and yet the deed has cost me many a pang. It seemed innoxious; the old man dead, insolvent; myself starving; his son ignorant of all - to whom could they be of use, for it required thousands to work them? And yet with all my wealth and power what memory shall I leave? Not a relative in the world, except a barbarian. Ah! had I a child like the beautiful daughter of Gerard. I have seen her. He must be a fiend who could injure her. I am that fiend. Let me see what can be done. What if I married her?" But Hatton did not offer marriage to Sybil. He did much to make her stay in London pleasant; but there was something about the maiden that awed while it fascinated him. A Catholic himself, Hatton was not surprised to hear from Gerard of Sybil's wish to enter a convent. "And to my mind she is right. My daughter cannot look to marriage; no man that she could marry would be worthy of her." This did not deter Hatton from considering how the papers relating to Gerard's lost estates could be recovered. The first move was an action entered against Lord de Mowbray, and this brought that distinguished peer to Mr. Hatton's chambers in the Temple, for Hatton was at that time advising Lord de Mowbray in the matter of reviving an ancient barony. Hatton easily quieted his client. "Mr. Walter Gerard can do nothing without the deed of '77. Your documents you say are all secure?" "They are at this moment in the muniment room of the tower of Mowbray Castle." "Keep them; this action is a feint." As for Mr. Baptist Hatton, the next time we see him a few months had elapsed. He is at the principal hotel in Mowbray in consultation with Stephen Morley. A great labour demonstration had taken place the previous night on the moors outside the town, and Gerard had been acclaimed as a popular hero. "Documents are in existence," said Hatton, "which prove the title of Walter Gerard to the proprietorship of this great district. Two hundred thousand human beings yesterday acknowledged the supremacy of Gerard. Suppose they had known that within the walls of Mowbray Castle were contained the proofs that Walter Gerard was the lawful possessor of the lands on which they live? Moral force is a fine thing, friend Morley, but the public spirit is inflamed here. You are a leader of the people. Let us have another meeting on the Moor! you can put your fingers in a trice on the man who will do our work. Mowbray Castle in their possession, a certain iron chest, painted blue, and blazoned with the shield of Valence, would be delivered to you. You shall have £10,000 down and I will take you back to London besides." "The effort would fail," said Stephen Morley. "Wages must drop still more, and the discontent here be deeper. But I will keep the secret; I will treasure it up." V. - Liberty - At a Price While Mr. Baptist Hatton and Stephen Morley discussed the possible recovery of the papers, much happened in London. Gerard became a marked man in the Chartist Convention, a member of a small but resolute committee. Egremont, now deeply in love with Sybil, declared his suit. "From the first moment I beheld you in the starlit arch of Marney, your image has never been absent from my consciousness. Do not reject my love; it is deep as your nature, and fervent as my own. Banish those prejudices that have embittered your existence. If I be a noble, I have none of the accidents of nobility. I cannot offer you wealth, splendour, and power; but I can offer you the devotion of an entranced being, aspirations that you shall guide, an ambition that you shall govern." "These words are mystical and wild," said Sybil in amazement. "You are Lord Marney's brother; I learnt it but yesterday. Retain your hand, and share your life and fortunes! You forget what I am. No, no, kind friend - for such I'll call you - your opinion of me touches me deeply. I am not used to such passages in life. A union between the child and brother of nobles and a daughter of the people is impossible. It would mean estrangement from your family, their hopes destroyed, their pride outraged. Believe me, the gulf is impassable." The Chartist petition was rejected by the House of Commons contemptuously. Riots took place in Birmingham. Sybil grew anxious for her father's safety. Egremont's speech in parliament on the presentation of the national petition created some perplexity among his aristocratic relatives and acquaintances. It was free from the slang of faction - the voice of a noble who had upheld the popular cause, who had pronounced that the rights of labour were as sacred as those of property, that the social happiness of the millions should be the statesman's first object. Sybil, enjoying the calm of St. James's Park on a summer morning, read the speech with emotion, and while she still held the paper the orator himself stood before her. She smiled without distress, and presently confided to Egremont that she was unhappy, about her father. "I honour your father," said Egremont "Counsel him to return to Mowbray. Exert every energy to get him to leave London at once - to-night if possible. After this business at Birmingham the government will strike at the convention. If your father returns to Mowbray and is quiet, he has a chance of not being disturbed." Sybil returned and warned her father. "You are in danger," she cried, "great and immediate. Let us quit this city to-night." "To-morrow, my child," Walter Gerard assured her, "we will return to Mowbray. To-night our council meets, and we have work of utmost importance. We must discountenance scenes of violence. The moment our council is over I will come back to you." But Walter Gerard did not return. While Sybil sat and waited, Stephen Morley entered the room. His manner was strange and unusual. "Your father is in danger; time is precious. I can endure no longer the anguish of my life. I love you, and if you will not be mine, I care for no one's fate. I can save your father. If I see him before eight o'clock, I can convince him that the government knows of his intentions, and will arrest him to-night. I am ready to do this service - to save the father from death and the daughter from despair, if she would but only say to me: 'I have but one reward, and it is yours.'" "It is bitter, this," said Sybil, "bitter for me and mine; but for you pollution, this bargaining of blood. In the name of the Holy Virgin I answer you - no!" Morley rushed frantically from the room. Sybil, in despair, made her way to a coffee-house near Charing Cross, which she knew had been much frequented by members of the Chartist Convention. Here, after some delay, she was given the fatal address in Hunt Street, Seven Dials. Sybil arrived at the meeting a few minutes before the police raided the premises. She was found with her father, and taken with him and six other men to Bow Street Police Station. A note to Egremont procured her release in the early hours of the morning. Walter Gerard in due time was sent to trial, convicted and sentenced to eighteen month's confinement in York Castle. VI. - Within the Castle Walls In 1842 came the great stoppage of work. The mills ceased; the miners went "to play," despairing of a fair day's wage for a fair day's work; and the inhabitants of Woodgate - the Hell-cats, as they were called-stirred up by a Chartist delegate, sallied forth with Simon Hatton, named the "liberator," at their head to deal ruthlessly with all "oppressors of the people." They sacked houses, plundered cellars, ravaged provision shops, destroyed gas-works and stormed workhouses. In time they came to Mowbray. There the liberator came face to face with Baptist Hatton without recognising his brother. Stephen Morley and Baptist Hatton were in close conference. "The times are critical," said Hatton. "Mowbray may be burnt to the ground before the troops arrive," Morley replied. "And the castle, too," said Hatton quietly. "I was thinking only yesterday of a certain box of papers. To business, friend Morley. This savage relative of mine cannot be quiet. If he does not destroy Trafford's Mill it will be the castle. Why not the castle instead of the mill?" Trafford's Mill was saved by the direct intervention of Walter Gerard. All the people of Mowbray knew the good reputation of the Traffords, and Gerard's eloquence turned the mob from the attack. While the liberator and the Hell-cats hesitated, a man named Dandy Mick, prompted by Morley, urged that a walk should be taken in Lord de Mowbray's park. The proposition was received with shouts of approbation. Gerard succeeded in detaching a number of Mowbray men, but the Hell-cats, armed with bludgeons, poured into the park and on to the castle. Lady de Mowbray and her friends made their escape, taking Sybil, who had sought refuge from the mob, with them. Mr. St. Lys gathered a body of men in defence of the castle, but came too late to prevent the entrance of the Hell-cats. Singularly enough, Morley and one or two of his followers entered with the liberator. The first great rush was to the cellars, and the invaders were quickly at work knocking off the heads of bottles, and brandishing torches. Morley and his lads traced their way down a corridor to the winding steps of the Round Tower, and forced their way into the muniment room of the castle. It was not till his search had nearly been abandoned in despair that he found the small blue box blazoned with the arms of Valence. He passed it hastily to a trusted companion, Dandy Mick, and bade him deliver it to Sybil Gerard at the convent. At this moment the noise of musketry was heard; the yeomanry were on the scene. Morley, cut off from flight by the military, was shot, pistol in hand, with the name of Sybil on his lips. "The world will misjudge me," he thought - "they will call me hypocrite, but the world is wrong." The man with the box escaped through the window, and in spite of the fire, troopers, and mob, reached the convent in safety. The castle was burnt to the ground by the torches of the Hell-cats. Sybil, separated from her friends, found herself surrounded by a band of drunken ruffians. She was rescued by a yeomanry officer, who pressed her to his heart. "Never to part again," said Egremont. Under Egremont's protection, Sybil returned to the convent, and there in the courtyard they found Dandy Mick, who had refused to deliver his charge, and was lying down with the blue box for his pillow. He had fulfilled his mission. Sybil, too agitated to perceive all its import, delivered the box into the custody of Egremont, who, bidding farewell to Sybil, bade Mick follow him to his hotel. While these events were happening, Lord Marney, hearing an alarmed and exaggerated report of the insurrection, and believing that Egremont's forces were by no means equal to the occasion, had set out for Mowbray with his own troop of yeomanry. Crossing the moor, he encountered Walter Gerard with a great multitude, whom Gerard headed for purposes of peace. His mind inflamed, and hating at all times any popular demonstration, Lord Marney hastily read the Riot Act, and the people were fired on and sabred. The indignant spirit of Gerard resisted, and the father of Sybil was shot dead. Instantly arose a groan, and a feeling of frenzy came over the people. Armed only with stones and bludgeons they defied the troopers, and rushed at the horsemen; a shower of stones rattled without ceasing on the helmet of Lord Marney, nor did the people rest till Lord Marney fell lifeless on Mowbray Moor, stoned to death. The writ of right against Lord de Mowbray proved successful in the courts, and his lordship died of the blow. For a long time after the death of her father Sybil remained in helpless woe. The widowed Lady Marney, however, came over one day, and carried her back to Marney Abbey, never again to quit it until the bridal day, when the Earl and Countess of Marney departed for Italy. Though the result was not what Mr. Hatton had once anticipated, the idea that he had deprived Sybil of her inheritance had, ever since he had become acquainted with her, been the plague-spot of Hatton's life, and there was nothing he desired more than to see her restored to those rights, and to be instrumental in that restoration. Dandy Mick was rewarded for all the dangers he had encountered in the service of Sybil, and was set up in business by Lord Marney. A year after the burning of Mowbray Castle, on the return of the Earl and Countess of Marney to England, the romantic marriage and the enormous wealth of Lord and Lady Marney were still the talk in fashionable circles. * * * * * |