|

|

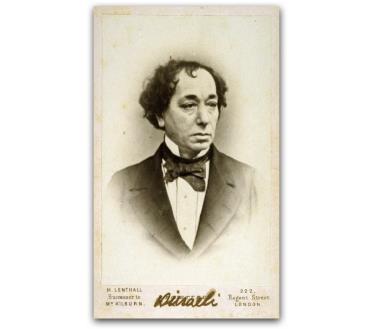

by Benjamin Disraeli The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (1847) Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield (December 21, 1804, - 1881) was not only a British Conservative Prime Minister, but also a novelist of significant powers. His books reflect his political views and remain important sources for the lives and opinions of the mid-nineteenth century. Abridged: JH For more works by Disraeli, see The Index I. - Tancred Goes Forth on His Quest Tancred, the Marquis of Montacute, was certainly strangely distracted on his twenty-first birthday. He stood beside his father, the Duke of Bellamont, in the famous Crusaders' gallery in the Castle of Montacute, listening to the congratulations which the mayor and corporation of Montacute town were addressing to him; but all the time he kept his eyes fixed on the magnificent tapestries from which the name of the gallery was derived. His namesake, Tancred of Montacute, had distinguished himself in the Third Crusade by saving the life of King Richard at the siege of Ascalon, and his exploits were depicted on the fine Gobelins work hanging on the walls of the great hall. Oblivious of the gorgeous ceremony in which he was playing the principal part, the young Marquis of Montacute stared at the pictures of the Crusader, and a wild, fantastical idea took hold of him. He was the only child of the Duke of Bellamont, and all the high nobility of England were assembled to celebrate his coming of age. Everything that fortune could bestow seemed to have been given to him. He was the heir of the greatest and richest of English dukes, and his life was made smooth and easy. His father had got a seat in parliament waiting for him, and his mother had already selected a noble and beautiful young lady for his wife. Neither of them had yet consulted their son, but Tancred was so sweet and gentle a boy that they did not dream he would oppose their wishes. They had planned out his life for him ever since he was born, with the view to educating him for the position which he was to occupy in the English aristocracy, and he had always taken the path which they had chosen for him. In the evening, the duke summoned his son into his library. "My dear Tancred," he said, "I have a piece of good news for you on your birthday. Hungerford feels that he cannot represent our constituency now that you have come of age, and, with great kindness, he is resigning his seat in your favour. He says that the Marquis of Montacute ought to stand for the town of Montacute, so you will be able to enter parliament at once." "But I do not wish to enter parliament," said Tancred. The duke leant back from his desk with a look of painful surprise on his face. "Not enter parliament?" he exclaimed. "Every Lord Montacute has gone into the House of Commons before taking his seat in the House of Lords. It is an excellent training." "I am not anxious to enter the House of Lords either," said Tancred. "And I hope, my dear father," he added, with a smile that lit up his young, grave, beautiful face, "that it will be very, very long before I succeed to your place there." "What, then, do you intend to do, my boy?" said Bellamont, in intense perplexity. "You are the heir to one of the greatest positions in the state, and you have duties to perform. How are you going to fit yourself for them?" "That is what I have been thinking of for years," said Tancred. "Oh, my dear father, if you knew how long and earnestly I have prayed for guidance! Yes, I have duties to perform! But in this wild, confused, and aimless age of ours, what man can see what his duties are? For my part, I cannot find that it is my duty to maintain the present order of things. In nothing in our religion, our government, our manners, do I find faith. And if there is no faith, how can there be any duty? We have ceased to be a nation. We are a mere crowd, kept from utter anarchy by the remains of an old system which we are daily destroying." "But what would you do, my dear boy?" said the duke, pale with anxiety. "Have you found any remedy?" "No," said Tancred mournfully. "There is no remedy to be found in England. Oh, let me save myself, father! Let me save our people from the corruption and ruin that threaten us!" "But what do you want to do? Where do you want to go?" said the duke. "I want to go to God!" cried the young nobleman, his blue eyes flaming with a strange light "How is it that the Almighty Power does not send down His angels to enlighten us in our perplexities? Where is the Paraclete, the Comforter Who was promised us? I must go and seek him." "You are a visionary, my boy," said the duke, gazing at him in blank astonishment. "Was the Montacute that fought by the side of King Richard in the Holy Land a visionary?" said Tancred. "All I ask is to be allowed to follow in his footsteps. For three days and three nights he knelt in prayer at the tomb of his Redeemer. Six centuries and more have gone by since then. It is high time that we renewed our intercourse with the Most High in the country of His chosen people. I, too, would kneel at that tomb. I, too, surrounded by the holy hills and groves of Jerusalem, would lift my voice to Heaven, and ask for inspiration." "But surely God will hear your prayers in England as well as in Palestine?" "No," said his son. "He has never raised up a prophet or a great saint in this country. If we want Him to speak to us as He spoke to the men of old, we must go, like the Crusaders, to the Holy Land." Finding that he could not turn his son from the strange course on which he was bent, the duke got a great prelate to try and persuade him that all was for the best in the best of all possible worlds. "We live in an age of progress," reasoned the philosophic bishop. "Religion is spreading with the spread of civilisation. How all our towns are growing! We shall soon see a bishop in Manchester." "I want to see an angel in Manchester," replied Tancred. It was no use arguing with a man who talked in this way, and the duke gave Tancred permission to set out on his new crusade. II. - The Vigil by the Tomb The moon sank behind the Mount of Olives, leaving the towers, minarets, and domes of Jerusalem in deep shadow; the lamps in the city went out, and every outline was lost in gloom; but the Church of the Holy Sepulchre still shone in the darkness like a beacon light. There, while every soul in Jerusalem slumbered, Tancred knelt in prayer by the tomb of Christ, under the lighted dome, waiting for the fire from heaven to strike into his soul. His strange vigil was the talk of Syria. It is remarkable how quickly news travels in the East. "Do you know," said Besso, Rothschild's agent, to his foster-son Fakredeen, an emir of Lebanon, as they sat talking in a house near the gate of Sion, "the young Englishman has brought me such a letter that if he were to tell me to rebuild Solomon's temple, I must do it!" "He must be fabulously rich!" said Fakredeen, with a sigh. "What has he come here for? The English do not come on pilgrimages. They are all infidels." "Well, he has come on a pilgrimage," said Besso, "and he is the greatest of English princes. He kneels all night and day in the church over there." Yes, after a week of solitude, fasting, and prayer, Tancred was keeping vigil before the empty Sepulchre, where Tancred of Montacute had knelt six hundred years before. Day after day, night after night, he prayed for inspiration, but no divine voice broke in upon his impassioned reveries. It was for him that Alonzo Lara, the prior of Terra Santa, kept the light burning all night long at the Holy Sepulchre, for the Spaniard had been moved by the deep faith of the young English nobleman. And one day he said to him: "Sinai led to Calvary. I think it would be wise for you to trace the path backward from Calvary to Sinai." It was extremely perilous at that time to adventure into the great desert, for the wild Bedouin tribes were encamped there. But, in spite of this, Tancred made arrangements with an Arabian chief, Sheikh Hassan, and set out for Sinai at the head of a well-armed band of Arabs. "Ah!" said the sheikh, as they entered the mountainous country, after a three days' march across the wilderness. "Look at these tracks of horses and camels in the defile. The marks are fresh. See that your guns are primed!" he cried to his men. As he spoke a troop of wild horsemen galloped down the ravine. "Hassan," one of them shouted, "is that the brother of the Queen of the English with you? Let him ride with us, and you may return in peace." "He is my brother, too," said Hassan. "Stand aside, you sons of Eblis, or you shall bite the earth." A wild shout from every height of the defile was the answer. Tancred looked up. The crest on either side was lined with Bedouins, each with his musket levelled. "There is only one thing for us to do," said Tancred to Hassan. "Let us charge through the defile, and die like men!" Seizing his pistols, he shot the first horseman through the head, and disabled another. Then he charged down the ravine, and Hassan and his men followed, and scattered the horsemen before them. The Bedouins fired down on them from the crests, and, in a few moments, the place was filled with smoke, and Tancred could not see a yard around him. Still he galloped on, and the smoke suddenly drifted, and he found himself at the mouth of the defile, with a few followers behind him. A crowd of Bedouins were waiting for him. "Die fighting! Die fighting!" he shouted. Then his horse stumbled, stabbed from beneath by a Bedouin dagger, and fell in the sand. Before he could get his feet out of the stirrups, he was overpowered and bound. "Don't hurt him," said the Bedouin chief. "Every drop of his blood is worth ten thousand piastres." Late that night, as Amalek, the great Rechabite Bedouin sheikh, was sitting before his tent, a horseman rode up to him. "Salaam," he cried. "Sheikh of sheikhs, it is done! The brother of the Queen of England is your slave!" "Good!" said Amalek. "May your mother eat the hump of a young camel! Is the brother of the queen with Sheikh Salem?" "No," said the horseman, "Sheikh Salem is in paradise, and many of our men are with him. The brother of the Queen of the English is a mighty warrior. He fought like a lion, but we brought his horse down at last and took him alive." "Good!" said Amalek. "Camels shall be given to all the widows of the men he has killed, and I will find them new husbands. Go and tell Fakredeen the good news!" Amalek and Fakredeen would not have cared had they lost a hundred men in the affair. The Bedouin chief and the emir of Lebanon could bring into the field more than twenty thousand lances, and the capture of Tancred was part of a political scheme which they were engineering for the conquest of Syria. They knew from Besso that the young English prince was fabulously rich, and, as they wanted arms, they meant to hold him to the extraordinary ransom of two million piastres. "My foster father will pay it," said Fakredeen. "He told me that he would have to rebuild Solomon's temple if the English prince asked him to. We will get him to help us rebuild Solomon's empire." III. - The Vision on the Mount On the wild granite scarp of Mount Sinai, about seven thousand feet above the blue seas that lave its base, is a small plain hemmed in by pinnacles of rock. In the centre of the plain are a cypress tree and a fountain. This is the traditional scene of the greatest event in the history of mankind. It was here that Moses received the divine laws on which the civilisation of the world is based. Tancred of Montacute knelt down on the sacred soil, and bowed his head in prayer. Far below him, in one of the green-valleys sloping down to the sea, Fakredeen and a band of Bedouins pitched their tents for the night, and talked in awed tones of their strange companion. Wonderful is the power of soul with which a great idea endues a man. The young emir of Lebanon and his men were no longer the captors of Tancred, but his followers. He had preached to them with the eyes of flame and the words of fire of a prophet; and they now asked of him, not a ransom, but a revelation. They wanted him to bring down from Sinai the new word of power, which would bind their scattered tribes into a mighty nation, with a divine mission for all the world. What was this word to be? Tancred did not know any more than his followers, and he knelt all day long under the Arabian sun, waiting for the divine revelation. The sunlight faded, and the shadows fell around him, and he still remained bowed in a strange, quiet ecstasy of expectation. But at last, lifting up his eyes to the clear, starry sky of Arabia, he prayed: "O Lord God of Israel, I come to Thine ancient dwelling-place to pour forth the heart of tortured Europe. Why does no impulse from Thy renovating will strike again into the soul of man? Faith fades and duty dies, and a profound melancholy falls upon the world. Our kings cannot rule, our priests doubt, and our multitudes toil and moan, and call in their madness upon unknown gods. If this transfigured mount may not again behold Thee, if Thou wilt not again descend to teach and console us, send, oh send, one of the starry messengers that guard Thy throne, to save Thy creatures from their terrible despair!" As he prayed all the stars of Arabia grew strangely dim. The wild peaks of Sinai, standing sharp and black in the lucid, purple air, melted into shadowy, changing masses. The huge branches of the cypress-tree moved mysteriously above his head, and he fell upon the earth senseless and in a trance. It seemed to Tancred that a mighty form was bending over him with a countenance like an oriental night, dark yet lustrous, mystical yet clear. The solemn eyes of the shadowy apparition were full of the brightness and energy of youth and the calm wisdom of the ages. "I am the Angel of Arabia," said the spectral figure, waving a sceptre fashioned like a palm-tree, "the guardian spirit of the land which governs the world; for its power lies neither in the sword nor in the shield, for these pass away, but in ideas which are divine. All the thoughts of every nation come from a higher power than man, but the thoughts of Arabia come directly from the Most High. You want a new revelation to Christendom? Listen to the ancient message of Arabia! "Your people now hanker after other gods than the God of Sinai and Calvary. But the eternal principles of that Arabian faith, which moulded them from savages into civilised men when they descended from their northern forests fifteen hundred years ago, and spread all over the world, can alone breathe new vigour into them, now that they are decaying in the dust and fever of their great cities. Tell them that they must cease from seeking in their vain philosophies for the solution of their social problems. Their, longing for the brotherhood of mankind can only be satisfied when they acknowledge the sway of a common father. Tell them that they are the children of God. Announce the sublime and solacing doctrine of theocratic equality. Fear not, falter not. Obey the impulse of thine own spirit, and find a ready instrument in every human being." A sound as of thunder roused Tancred from his trance. Above him the mountains rose sharp and black in the clear purple air, and the Arabian stars shone with undimmed brightness; but the voice of the angel still lingered in his ear. He went down the mountain; at its base he found his followers sleeping amid their camels. He aroused Fakredeen, and told him that he had received the word which would bind together the warring nations of Arabia and Palestine, and reshape the earth. IV. - The Mystic Queen "It has been a great day," said Tancred to Fakredeen, as they were sitting some months afterwards in the castle of the young emir of Lebanon, where all the princes of Syria had assembled to discuss the foundation of the new empire. "If your friends will only work together as they promise, Syria is ours." "Even Lebanon," said Fakredeen, "can send forth more than fifty thousand well-armed footmen, and Amalek is gathering all the horsemen of the desert, from Petraea to Yemen, under our banner. If we can only win over the Ansarey," he continued, "we shall have all Syria and Arabia as a base for our operations." "The Ansarey?" exclaimed Tancred. "They hold the mountains around Antioch, which are the key of Palestine, don't they? What is their religion? Do you think that the doctrine of theocratic equality would appeal to them as it did to the Arabians?" "I don't know," said the emir. "They never allow strangers to enter their country. They are a very ancient people, and they fight so well in their mountains that even the Turks have not been able to conquer them." "But can't we make overtures?" said Tancred. "That is what I have done," said Fakredeen. "The Queen of the Ansarey has heard about you, and I have arranged that we should go and see her as soon as the Syrian assembly was over. Everything is ready for our journey, so, if you like, we will start at once." It was a difficult expedition, as the Queen of the Ansarey was then waging war on the Turkish pasha of Aleppo. Happily, the travellers came upon a band of Ansareys who were raiding the Turkish province, and were led by them through their black ravines to the fortress palace of the queen. She received them, sitting on her divan, clothed in a purple robe, and shrouded in a long veil. This she took off when Tancred came towards her, and he marvelled at the strangeness of her beauty. There was nothing oriental about her. She was a Greek girl of the ancient type, with violet eyes, fair cheeks, and dark hair. "Prince," she said, "we are a people who wish neither to see nor to be seen. We do not care what goes on in the world around. Our mountains are wild and barren, but while Apollo dwells among us, we do not care for gold, or silk, or jewels." "Apollo!" cried Tancred. "Are the gods of Olympus still worshipped on earth?" "Yes, Apollo still lives among us, and another greater than Apollo," said the young queen, looking at Tancred long and earnestly. "Follow me, and you shall now behold the secret of the Ansarey." Her maidens adorned her with a garland of roses, and put a garland on the head of Tancred, and she led him through a portal of bronze, down an underground passage, into an Ionic temple, filled with the white and lovely forms of the gods of ancient Greece. "Do you know this?" said the queen to Tancred, looking at a statue in golden ivory, and then at the young Englishman, whose clear-cut features and hyacinthine locks curiously resembled those of the carven image. "It is Phoebus Apollo," said Tancred, and, moved by admiration at the beauty of the figure, he murmured some lines of Homer. "Ah, you know all!" cried the queen. "You know our secret language. Yes, this is Phoebus Apollo. He used to stand in Antioch in the ancient days before the Christians drove us into the mountains. And look," she said, pointing to the statue beside Apollo, "here is the Syrian goddess before whom the pilgrims of the world once knelt. She is named Astarte, and I am called after her." "Oh, angels watch over me!" said Tancred to himself as Queen Astarte fixed her violet eyes upon him with a glance of love that could not be mistaken, and led him back into the hall of audience. There he saw Fakredeen bending over a maiden with a flower-like face, and large, dark, lustrous eyes. "She is my foster-sister, Eva," said Fakredeen. "The Ansareys captured her on the plain of Aleppo." Tancred had met Eva at the house of Besso in Jerusalem, but she did not then exercise over him the strange charm which now drew him to her side. It seemed to him that the beautiful Jewish girl had been sent to help him in his struggle against the heathen spells of Astarte. As he was meditating how he could rescue her, a messenger came in, and announced that the pasha of Aleppo had invaded the mountains at the head of 5,000 troops. "Ah!" cried Astarte. "Few of them will ever see Aleppo again. I have 25,000 men under arms, and you, my prince," she said, turning to Tancred, "shall command them." Tancred had learnt something of the arts of mountain warfare from Sheikh Amalek. He allowed the Turkish troops to penetrate into the heart of the wild hills, and then, as they were marching down a long defile, he attacked them from the crests above, shooting them down like sheep and burying them in avalanches of rolling rock. Instead of returning to the fortress palace, he sent his men on ahead, and rode out alone into the desert, and went through the Syrian wilderness back to Jerusalem. Riding up to the door of Besso's house by Sion gate, he asked if there were any news of Eva. A negro led him into a garden, and there, sitting by the side of a fountain, was the lovely Jewish maiden. "So Fakredeen brought you safely away, Eva," he said tenderly. "I was afraid that Astarte meant to harm you." "She would have killed me," said Eva, "if she could. I am afraid that your faith in your idea of theocratic equality has been destroyed by the Ansareys. How can you build up an empire in a land divided by so many jarring creeds? Do you still believe in Arabia?" "I believe in Arabia," cried Tancred, kneeling down at her feet, "because I believe in you. You are the angel of Arabia, and the angel of my life. You cannot guess what influence you have had on my fate. You came into my life like another messenger from God. Thanks to you, my faith has never faltered. Will you not share it, dearest?" He clasped her hand, and gazed with passionate adoration into her face. As her head fell upon his shoulder, the negro came running to the fountain. "The Duke of Bellamont!" he said to Tancred. Tancred looked up, and saw the Duke of Bellamont coming through the pomegranate trees of the garden. "Father," he said, advancing towards the duke, "I have found my mission in life, and I am going to marry this lady." * * * * * |