|

|

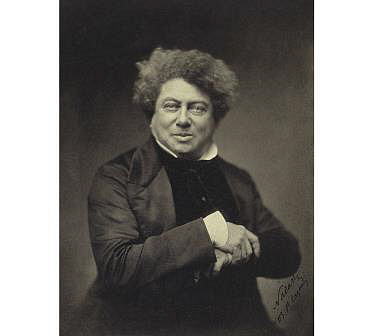

by Alexandre Dumas The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (Paris, 1844) Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870), known as Alexandre Dumas, père, is one of the most widely read and translated of all French authors. His historical romances have been adapted into at least 100 films, into plays and comic books. Abridged: JH/GH For more works by Alexandre Dumas, see The Index D'Artagnan was without acquaintances in Paris, and now on the very day of his arrival he was committed to fight with three of the most distinguished of the king's musketeers. Coming from Gascony, a youth with all the pride and ambition of his race, D'Artagnan had brought no money; with him, but only a letter of introduction from his father to M. de Treville, captain of the musketeers. But he had been taught that by courage alone could a man now make his way to fortune, and that he was to bear nothing, save from the cardinal - the great Cardinal Richelieu, or from the king - Louis XIII. It was immediately after his interview with M. de Treville that D'Artagnan, well trained at home as a swordsman, quarrelled with the three musketeers. First, on the palace stairs, he ran violently into Athos, who was suffering from a wounded shoulder. "Excuse me," said D'Artagnan. "Excuse me, but I am in a hurry." "You are in a hurry?" said the musketeer, pale as a sheet. "Under that pretence, you run against me; you say 'Excuse me!' and you think that sufficient. You are not polite; it is easy to see that you are from the country." D'Artagnan had already passed on, but this remark made him stop short. "However far I may come it is not you, monsieur, who can give me a lesson in manners, I warn you." "Perhaps," said Athos, "you are in a hurry now, but you can find me without running after me. Do you understand me." "Where, and when?" said D'Artagnan. "Near the Carmes-Deschaux at noon," replied Athos. "And please do not keep me waiting, for at a quarter past twelve I will cut off your ears if you run." "Good!" cried D'Artagnan. "I will be there at ten minutes to twelve." At the street gate Porthos was talking with the soldiers on guard. Between the two there was just room for a man to pass, and D'Artagnan hurried on, only to find himself enveloped in the long velvet cloak of Porthos, which the wind had blown out. "The fellow must be mad," said Porthos, "to run against people in this manner! Do you always forget your eyes when you happen to be in a hurry?" "No," replied D'Artagnan, who, in extricating himself from the cloak, had observed that the handsome cloth of gold coat worn by Porthos was only gold in front and plain buff at the back, "no, and thanks to my eyes, I can see what others cannot see." "Monsieur," said Porthos angrily, "you stand a chance of getting chastised if you run against musketeers in this fashion. I shall look for you, at one o'clock behind the Luxembourg." "Very well, at one o'clock then," replied D'Artagnan, turning into the street. A few minutes later D'Artagnan annoyed Aramis, the third musketeer, who was chatting with some gentleman of the king's musketeers. As D'Artagnan came up Aramis accidentally dropped an embroidered pocket-handkerchief and covered it at once with his foot to prevent observation. D'Artagnan, conscious of a certain want of politeness in his treatment of Athos and Porthos, and determined to be more obliging in future, stooped and picked up the handkerchief - much to the vexation of Aramis, who denied all claim to the delicate piece of cambric. D'Artagnan not taking the rebukes of Aramis in good part, they fixed two o'clock as the hour of meeting. The two young men bowed and separated, Aramis going up the street which led to the Luxembourg, whilst D'Artagnan, finding that it was near noon, took the road to the Carmes-Deschaux, saying to himself, "Decidedly I can't draw back; but at least if I am killed, I shall be killed by a musketeer." Knowing nobody in Paris, D'Artagnan went to his appointment without a second. It was just striking twelve when he arrived on the ground, and Athos, still suffering from his old wound on the shoulder, was already waiting for his adversary. Athos explained with all politeness that his seconds had not yet arrived. "If you are in great haste, monsieur," said D'Artagnan, "and if it be your will to despatch me at once, do not inconvenience yourself. I am ready. But if you would wait three days till your shoulder is healed, I have a miraculous balsam given me by my mother, and I am sure this balsam will cure your wound. At the end of three days it would still do me a great honour to be your man." "That is well said," said Athos, "and it pleases me. Thus spoke the gallant knights of Charlemagne. Monsieur, I love men of your stamp, and I can tell that if we don't kill each other, I shall enjoy your society. But here comes my seconds." "What!" cried D'Artagnan as Porthos and Aramis appeared. "Are these gentlemen your seconds?" "Yes," replied Athos. "Are you not aware that we are never seen one without the others, and that we are called the three inseparables?" "What does this mean?" said Porthos, who had now come up and stood astonished. "This is the gentleman I am to fight with," said Athos, pointing to D'Artagnan and saluting him. "Why I am also going to fight with him," said Porthos. "But not before one o'clock," replied D'Artagnan. "Well, and I also am going to fight with that gentleman," said Aramis. "But not till two o'clock," said D'Artagnan calmly. "And now you are all assembled, gentleman, permit me to offer you my excuses." At this word "excuses" a cloud passed over the brow of Athos, a haughty smile curled the lip of Porthos, and a negative sign was the reply of Aramis. "You do not understand me, gentleman," said D'Artagnan, throwing up his head. "I ask to be excused in case I should not be able to discharge my debt to all three; for M. Athos has the right to kill me first. And now, gentleman, I repeat, excuse me, but on that account only, and - guard!" At these words D'Artagnan drew his sword, and at that moment so elated was he that he would have drawn his sword against all the musketeers in the kingdom. Scarcely had the two rapiers sounded on meeting, when a company of the cardinal's guards appeared on the scene. At that time there was not only a standing feud between the king's musketeers and the guards of Cardinal Richelieu, there was also a prohibition against duelling. "The cardinal's guards! The cardinal's guards!" cried Aramis and Porthos at the same time. "Sheathe swords, gentlemen! Sheathe swords!" But it was too late. Jussac, commander of the guards, had seen the combatants in a position which could not be mistaken. "Hullo, musketeers," he called out; "fighting, are you, in spite of the edicts? Well, duty before everything. Sheathe your swords, please, and follow us." "That is quite impossible," said Aramis politely. "The best thing you can do is to pass on your way." "We shall charge upon you, then," said Jussac. "if you disobey." "There are five of them," said Athos, "and we are but three. We shall be beaten, and must die on the spot, for on my part I will never face my captain as a conquered man." Athos, Porthos, and Aramis instantly closed in, and Jussac drew up his soldiers. In that short interval D'Artagnan determined on the part he was to take; it was a decision of life-long importance. He had to choose between the king and the cardinal, and the choice made, it must be persisted in. He turned towards Athos and his friends. "Gentlemen," said he, "allow me to correct your words. You said you were but three, but it appears to me we are four. I do not wear the uniform, but my heart is that of a musketeer." "Withdraw, young man, and save your skin!" cried Jussac. The three musketeers thought of D'Artagnan's youth, and dreaded his inexperience. "Try me, gentlemen," said D'Artagnan, "and I swear to you that I will never go hence if we are conquered." Athos pressed the young man's hand, and exclaimed, "Well, then! Athos, Porthos, Aramis, and D'Artagnan, forward!" The nine combatants rushed upon each other with fury, and the battle ended in the utter discomfiture of the cardinal's guards, one of whom was slain and three badly wounded. The musketeers returned walking arm in arm. D'Artagnan marched between Athos and Porthos, his heart full of delight. "If I am not yet a musketeer," said he to his new friends, "at least, I have entered upon my apprenticeship, haven't I?" The king, always jealous of Richelieu's guards, was extremely pleased when he heard from M. de Treville of the fight that had taken place. He gave D'Artagnan a handful of gold, and promised him a place in the ranks of the musketeers at the first vacancy; in the meantime he was to join a company of royal guards. From this time the life of the four young men became common, for D'Artagnan fell quite easily into the habits of his three friends. Athos, who was scarcely thirty years old, was of great personal beauty and intelligence of mind. He never spoke of women, he never laughed, rarely smiled, and his reserved and silent habits seemed to make him a much older man. Porthos was exactly the opposite of Athos. He not only talked much, but he talked loudly, not caring whether anyone listened to him. He would talk about anything except the sciences, alleging that from childhood dated his inveterate hatred of learning. The physical strength of Porthos was enormous, and with all the vanity of a child he was a thoroughly loyal and brave man. As for Aramis, he always gave out that he intended to take orders in the Church, and was merely a musketeer for the time being. Aramis revelled in intrigues and mysteries. What the real names of his comrades were D'Artagnan had no idea. That the names they bore had been assumed was all he knew. The motto of the four was "all for one, one for all." D'Artagnan had already earned the dislike of Cardinal Richelieu by his part in the fight with the cardinal's guards; it was not long before his daring gave greater cause for offence. The king suspected his wife, Anne of Austria, of being in love with the Duke of Buckingham, and the cardinal suspected the queen of intriguing with Buckingham against France. Now, a secret interview had taken place at the palace between Buckingham and the queen, and the cardinal, who employed spies everywhere, found out this as he found out everything, and determined to destroy the queen's reputation, for there was deadly enmity between Anne of Austria and Richelieu. Buckingham had received from the queen a set of diamond studs - a present from the king - as a keepsake; so the cardinal despatched a certain lady, a woman of rare beauty, known as "Milady," to England, to get hold of two of these studs. Then the cardinal, by fostering the royal suspicion, persuaded the king to give a grand ball whereat the queen should wear the diamond studs. By this means Louis would be convinced of Buckingham's visit, for the set of studs would be incomplete. The queen was in dispair. It was D'Artagnan and the three musketeers who saved her honour. D'Artagnan loved Madame Bonacieux, a confidential dressmaker of the queen's; and this woman, devoted to her royal mistress, gave D'Artagnan a secret note from the queen to Buckingham. D'Artagnan went at once to M. de Treville, obtained leave of absence for himself and his friends, and set out for England. It was not a minute too soon, for the cardinal had already made plans to prevent any such counter-move, giving orders that no one was to sail from France without a permit. Between Paris and Calais, Porthos, Aramis, and Athos were all left behind, wounded by Richelieu's guards, and D'Artagnan only effected a passage to Dover by fighting and nearly killing a young noble who held a permit from the cardinal to leave France. Once in England, D'Artagnan hastened to find Buckingham. The latter discovered, to his horror, that Milady had already become possessed cunningly of two of the precious studs, and D'Artagnan had to wait while the skill of the first English jeweller made good the loss beyond detection. He returned to Paris with the twelve studs in time for the royal ball. Milady had already given the two she had stolen to the cardinal, who had passed them on to the king. "What does this mean, Monsieur le Cardinal?" said the king severely, when in the middle of the ball he found, to his joy, that the queen was already wearing twelve diamonds. "It means, sire," the cardinal replied, with vexation, "that I was anxious to present her majesty with two studs, but did not dare to offer them myself." "I am very grateful," said Anne of Austria, fully alive to the cardinal's defeat, "only I am afraid these two studs must have cost your eminence as much as all the others cost his majesty." The man, D'Artagnan, to whom the queen owed this extraordinary triumph over her enemy, stood unknown in the crowd that gathered round the doors. It was only when the queen retired that someone touched him on the shoulder and bade him follow. He readily obeyed; D'Artagnan waited in an ante-room of the queen's apartments; he could hear voices within, and presently a hand and an arm, marvellously white and beautiful, came through the tapestry. D'Artagnan felt that this was his reward. He dropped on his knees, seized the hand, and touched it modestly with his lips. Then the hand was withdrawn, and in his own a ring was left. The tapestry closed, and his guide, no other than Bonacieux, reappeared and escorted him hastily to the corridor. The siege of La Rochelle was an important affair, one of the chief political events of the reign of Louis XIII. For a time D'Artagnan was separated from his friends, for the musketeers were escorting the king to the seat of war, and our intrepid Gascon was with the main army. It was now that D'Artagnan began to realise that he had attracted, not only the displeasure of the cardinal, but also the deadly hatred of Milady, the cardinal's secret agent, whose overtures at friendship, made in the cardinal's interest, he had insulted before leaving Paris, and whose secret shame he had discovered. Twice his life was nearly taken by hired assassins, and the third time a present of wine turned out to be poisoned. To add to his natural discomfort, Madame Bonacieux had disappeared from Paris, and probably was in prison. The arrival of the musketeers restored his spirits, and the four were again inseparable. One drawback to their intercourse was the fact that the cardinal and his spies were all over the camp, and that, consequently, it was difficult to talk confidentially without being overheard. In order to secure privacy for a conference, they decided to go and breakfast in a bastion near the enemy's lines, and wagered with some officers they would stay there an hour. It was a position of terrible danger, but the feat was accomplished, and the wild undertaking of the musketeers was acclaimed with tremendous enthusiasm in the French camp. The noise reached the cardinal's ears, and he inquired its meaning. "Monseigneur," said the officer, "three musketeers and a guard laid a wager that they would go and breakfast in the Bastion St. Gervais, and they breakfasted and held it for two hours against the enemy, killing I don't know how many Rochellais." "Did you inquire the names of those three musketeers?" "Yes, monseigneur. MM. Athos, Porthos, and Aramis." "Still the three braves!" muttered the cardinal. "And the guard?" "M. D'Artagnan!" "Still my reckless young friend! I must have these four men as my own." That same night the cardinal spoke to M. de Treville of the episode of the bastion, and gave permission for D'Artagnan to become a musketeer, "for such men should be in the same company," he said. One night during the siege, the three musketeers, seeking D'Artagnan, were met in a country lane by the cardinal, travelling, as he often did, with a single attendant. Athos recognised him, and the cardinal bade the three men escort him to a lonely inn. At the door they all alighted. The landlord of the inn received the cardinal, for he had been expecting an officer to visit a lady who was within. The three musketeers were accommodated in a large room on the ground floor, and the cardinal passed up the staircase as a man who knew his road. Porthos and Aramis sat down at the table to dice, while Athos walked up and down the room in a thoughtful mood. To his astonishment, Athos found that, the stovepipe being broken, he could hear all that was passing in the room above. "Listen, Milady," the cardinal was saying, "this affair is of utmost importance. A small vessel is waiting for you at the mouth of the river. You will go on board to-night and set sail to-morrow morning for England. Half an hour after I have gone, you will leave here. When you reach England, you will seek the Duke of Buckingham, explain to him that I have proofs of his secret interviews with the queen, and tell him that if England moves in support of the besieged in La Rochelle, I will at once ruin the queen." "But what if he persists in spite of this in making war?" said Milady. "If he persists? Why, then he must be got rid of. Some woman doubtless exists, handsome, young, and clever, who has a grievance against the duke; and some fanatic can be found to be her instrument." "The woman exists, and the fanatic will be found," returned Milady. "And now, will monseigneur permit me to speak of my enemies, as we have spoken of yours?" "Your enemies? Who are they?" asked Richelieu. "First, there is a meddlesome little woman called Bonacieux. She was in prison at Nantes, but has been conveyed to a convent by an order which the queen obtained from the king. Will your eminence find out where that convent is?" "I don't object to that." "Then I have a much more dangerous enemy than the little Bonacieux, and that is her lover, the wretch D'Artagnan. I will get you a thousand proofs that he has conspired with Buckingham." "Very well; get me proof, and I will send him to the Bastille." For a few seconds there was silence while the cardinal was writing a note. Athos at once got up and told his companions he would go out to see if the road was safe, and left the house. The cardinal gave his final instructions to Milady, and departed with Porthos and Aramis. No sooner had they turned an angle of the road than Athos re-entered the inn, marched boldly upstairs, and before he had been seen, had bolted the door. Milady turned round, and became exceedingly white. "The Count de la Fère!" she said. "Yes, Milady, the Count de la Fère in person. You believed him dead, did you not, as I believed you to be?" "What do you want? Why do you come here?" said Milady in a hollow voice. "I have followed your actions," said Athos sternly. "It was you who had Madame Bonacieux carried off; it was you who sent assassins after D'Artagnan, and poisoned his wine. Only to-night you have agreed to assassinate the Duke of Buckingham, and expect D'Artagnan to be slain in return. Now, I care nothing about the Duke of Buckingham; he is an Englishman, but D'Artagnan is my friend." "M. D'Artagnan insulted me," said Milady. "Is it possible to insult you?" said Athos. He drew out a pistol and cocked it. "Madame, you will instantly deliver to me the paper you have received from the cardinal; or, upon my soul, I will blow out your brains." Athos slowly raised his pistol until the weapon almost touched the woman's forehead. Milady knew too well that with this terrible man death would certainly come unless she yielded. She drew the paper out of her bosom and handed it to Athos. "Take it," she said, "and be accursed." Athos returned the pistol to his belt, unfolded the paper, and read: It is by my order, and for the good of the state, that the bearer of this has done what he has done. Dec. 3rd, 1627. RICHELIEU. Athos, without looking at the woman, left the inn, mounted his horse, and galloping across country, managed to get in front, on the road, before the cardinal had passed. For a second, Milady thought of pursuing the cardinal in order to denounce Athos; but unpleasant revelations might be made, and it seemed best to carry out her mission in England, and then, when she had satisfied the cardinal, to claim her revenge. Milady accomplished the assassination of the Duke of Buckingham at Portsmouth, and Richelieu was relieved of the fear of English intervention at La Rochelle. But the doom of Milady was at hand. The king, weary of the siege, had gone to spend a few days quietly at St. Germains, taking for an escort only twenty of the musketeers, and at Paris the four friends had obtained from M. de Treville a few days' leave of absence. Aramis had discovered the convent where Madame Bonacieux was confined; it was at Bethune, and thither the musketeers hastened. Unfortunately, Milady reached Bethune first. She had come there to await the cardinal's orders, and having ingratiated herself with the abbess, learnt that D'Artagnan was on his way with an order from the queen to take Madame Bonacieux to Paris. Milady immediately dispatched a messenger to the cardinal, and at the very moment when the musketeers were at the front entrance, she poured a powder into a glass of wine and bade Madame Bonacieux drink. "It is not the way I meant to avenge myself," said Milady, as she hastily left the convent by the back gate, "but, ma foi, we do what we must!" The deadly poison did its work. Constance Bonacieux expired in D'Artagnan's arms. Then the four musketeers, joined by Lord de Winter, who had arrived from England in hot pursuit of Milady, his sister-in-law, set out to overtake the woman who had wrought so much evil. They came up with Milady at a solitary house near the village of Erquinheim. The four servants of the musketeers guarded the house; Athos, D'Artagnan, Aramis, Porthos, and De Winter entered. "What do you want?" screamed Milady. "We want Charlotte Backson, first called Countess de la Fère, and afterwards Lady de Winter," said Athos. "M. D'Artagnan, it is for you to accuse her first." "I accuse this woman of having poisoned Constance Bonacieux, and of having attempted to poison me, and I accuse her of having engaged assassins to shoot me," said D'Artagnan. "I accuse this woman of having procured the assassination of the Duke of Buckingham," said Lord de Winter. "Moreover, my brother, who made her his heiress, died suddenly of a strange disease." "I married this woman and gave her my name and wealth, and found afterwards she was branded as a felon," said Athos. The musketeers and Lord de Winter passed sentence of death upon the miserable woman. She was taken out to the river bank, and beheaded, and her body dropped into the middle of the stream. "Let the justice of Heaven be done!" they cried in a loud voice. Within three days the musketeers were back in Paris, ready to return with the king to La Rochelle. Then the cardinal summoned D'Artagnan to his presence. "You are charged with having corresponded with the enemies of France, with having surprised state secrets, and with having attempted to thwart the plans of your general," said the cardinal. "The woman who charges me - a branded felon - Milady de Winter, is dead," replied D'Artagnan. "Dead!" exclaimed the cardinal. "Dead!" "We have tried her and condemned her," said D'Artagnan. Then he told the cardinal of the poisoning of Madame Bonacieux, and of the subsequent trial and execution. The cardinal shuddered before he answered quietly, "You will be tried and condemned." "Monseigneur," said D'Artagnan, "though I have the pardon in my pocket I am willing to die." "What pardon?" said the cardinal, in astonishment. "From the king?" "No, a pardon signed by your eminence." D'Artagnan produced the precious paper which Athos had forced Milady to give him before her journey to England. For a time the cardinal sat looking at the paper before him. Then he slowly tore it up. "Now I am lost." thought D'Artagnan. "But he shall see how a gentleman can die." The cardinal went to a table, and wrote a few lines on a parchment. "Here, monsieur," he said; "I have taken away from you one paper; I give you another. Only the name is wanting in this commission, and you must fill that up." D'Artagnan took the document with hesitation. He looked at it, saw it was a lieutenant's commission in the musketeers, and fell at the cardinal's feet. "Monseigneur, my life is yours. Dispose of it as you will. But I do not deserve this. I have three friends, all more worthy - - " The cardinal interrupted him. "You are a brave young man, D'Artagnan. Fill up this commission as you will." D'Artagnan sought out his friends, and offered the commission to them in turn. But each declined, and Athos filled in the name of D'Artagnan on the commission. "I shall soon have no more friends. Nothing but bitter recollections!" said D'Artagnan, thinking of Madame Bonacieux. "You are young yet," Athos answered. "In time these bitter recollections will give way to sweet remembrances." |