|

|

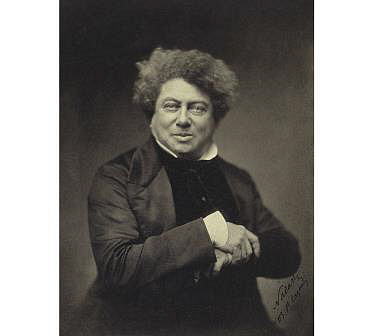

by Alexandre Dumas The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (Paris, 1845) Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870), known as Alexandre Dumas, père, is one of the most widely read and translated of all French authors. His historical romances have been adapted into at least 100 films, into plays and comic books. Abridged: JH/GH For more works by Alexandre Dumas, see The Index The great Richelieu was dead, and his successor, Cardinal Mazarin, a cunning and parsimonious Italian, was chief minister of France. Paris, torn and distracted by civil dissension, and impoverished by heavy taxation, was seething with revolt, and Mazarin was the object of popular hatred, Anne of Austria, the queen-mother (for Louis XIV. was but a child), sharing his disfavour with the people. It was under these circumstances that the queen recalled how faithfully D'Artagnan had once served her, and reminded Mazarin of that gallant officer, and of his three friends. Mazarin sent for D'Artagnan, who for twenty years had remained a lieutenant of musketeers, and asked him what had become of his friends. "I want you and your three friends to be of use to me," said the cardinal. "Where are your friends?" "I do not know, my lord. We parted company long ago; all three have left the service." "Where can you find them, then?" "I can find them wherever they are. It would be my business." "And what are the conditions for finding them?" "Money, my lord; as much money as the undertaking may require. Travelling is dear, and I am only a poor lieutenant in the musketeers." "You will be at my service when they are found?" asked Mazarin. "What are we to do?" "Don't trouble about that. When the time for action arrives you shall learn all that I require of you. Wait till that comes, and find out where your friends are." Mazarin gave D'Artagnan a bag of money, and the latter withdrew, to discover in the courtyard that the bag contained silver and not gold. "Crown pieces only, silver!" exclaimed D'Artagnan; "I guessed as much. Ah, Mazarin, Mazarin, you have no real confidence in me. So much the worse for you!" But the cardinal was rubbing his hands, and congratulating himself that he had discovered a secret for a tenth of the coin Richelieu would have spent on the matter. D'Artagnan first sought for Aramis, who was now an abbé, and lived in a convent and wrote sermons. But the heart of Aramis was not in religion, and when D'Artagnan found him, and the two had sat talking for some time, D'Artagnan said, "My friend, it seems to me that when you were a musketeer you were always thinking of the Church, and now that you are an abbé you are always longing to be a musketeer." "It's true," said Aramis. "Man is a strange bundle of inconsistencies. Since I became an abbé I dream of nothing but battles, and I practise shooting all day long here with an excellent master." Aramis indeed had both retained his swordsmanship and his interest in public affairs. But when D'Artagnan mentioned Mazarin, and the serious crisis in the state, Aramis declared that Mazarin was an upstart with only the queen on his side; and that the young king, the nobles, and princes, were all against him. Aramis was already on the side of Mazarin's enemies. He could not pledge himself to anyone, and the two separated. D'Artagnan went on to find Porthos, whose address he had learnt from Aramis. Porthos, who now called himself De Valon after the name of his estate, lived at ease as a country gentleman should; he was a widower and wealthy, but he was mortified because his neighbours were of ancient family and ignored him. He received D'Artagnan with open arms, and when at breakfast he confessed his weariness, D'Artagnan at once invited him to join him again and promised that he would get a barony for his services. "Go into harness again!" cried D'Artagnan. "Gird on your sword, and win a coronet. You want a title; I want money; the cardinal wants our help." "For my part," said the gigantic Porthos, "I certainly want to be made a baron." They talked of Athos, who lived on his estate at Bragelonne, and was now the Count de la Fère. And Porthos mentioned that Athos had an adopted son. "If we can get Athos, all will be well," said D'Artagnan. "If we cannot, we must do without him. We two are worth a dozen." "Yes," said Porthos, smiling at the remembrance of their old exploits; "but we four would be equal to thirty-six." "I have your word, then?" said D'Artagnan. "Yes. I will fight heart and soul for the cardinal; but - but he must make me a baron." "Oh, that's settled already!" said D'Artagnan. "I'll answer for your barony." With that he had his horse saddled, and rode on to the castle of Bragelonne. Athos was visibly moved at the sight of D'Artagnan, and rushed towards him and clasped him in his arms. D'Artagnan, equally moved, held him closely, while tears stood in his eyes. Athos seemed scarcely aged at all, in spite of his eight-and-forty years; but there was a greater dignity about his face. Formerly, too, he had been a heavy drinker, but now no signs of excess disturbed the calm serenity of his countenance. The presence of his son, whom he called Raoul - a boy of fifteen - seemed to explain to D'Artagnan the regenerated existence of Athos. Deeply as the heart of Athos was stirred at meeting his old comrade-in-arms, and sincere as his attachment was to D'Artagnan, the Count de la Fère would have nothing to do with any plan for helping Mazarin. D'Artagnan returned alone to await Porthos in Paris. The same night Athos and his son also left for Paris. Queen Henrietta of England, daughter of Henry IV. of France and wife of King Charles I., was lodged in the Louvre, while her husband lost his crown in the civil war. The queen had appealed to Mazarin either to send assistance to Charles I., or to receive him in France, and the cardinal had declined both propositions. Then it was that an Englishman, Lord de Winter, who had come to Paris to get help, appealed to Athos, whom he had known twenty years earlier, to come to England and fight for the king. Athos and Aramis at once responded, and waited on the queen, who received them in the large empty rooms - left unfurnished by the avarice of the cardinal - allotted to her in the Louvre. "Gentlemen," said the queen, "a few years ago I had around me knights, treasure, and armies. To-day look around, and know that in order to accomplish a plan which is dearer to me than life I have only Lord de Winter, the friend of twenty years, and you, gentlemen, whom I see for the first time, and whom I know but as my countrymen." "It is enough," said Athos, bowing low, "if the life of three men can purchase yours, madame." "I thank you, gentlemen. But hear me. My husband, King of England, is leading so wretched a life that death would be a welcome exchange for him. He has asked for the hospitality of France, and it has been refused him." "What is to be done?" said Athos. "I have the honour to inquire from your majesty what you desire Monsieur D'Herblay (as Aramis was named) and myself to do in your service. We are ready." "I, madame," said Aramis, "follow M. de la Fère wherever he leads, even to death, without demanding any reason; but when it concerns your majesty's service, no one precedes me." "Well, then, gentlemen," said the queen, "since it is thus, and since you are willing to devote yourselves to the service of a poor princess whom everybody has forsaken, this is what must be done for me. The king is alone with a few gentlemen whom he may lose any day, and he is surrounded by the Scotch, whom he distrusts. I ask much, too much, perhaps, for I have no title to ask it. Go to England, join the king, be his friends, his bodyguard; be with him on the field of battle and in his house. Gentlemen, in exchange I can only promise you my love; next to my husband and my children, and before everyone else, you will have my prayers and a sister's love." "Madame," said Athos, "when must we set out? we are ready!" The queen, moved to tears, held out her hand, which they kissed, and then, after receiving letters for the king, they withdrew. "Well," said Aramis, when they were alone, "what do you think of this business, my dear count?" "Bad!" replied Athos. "Very bad!" "But you entered on it with enthusiasm." "As I shall ever do when a great principle is to be defended. Kings are only strong by the aid of the aristocracy; but aristocracy cannot exist without kings. Let us then support monarchy in order to support ourselves." "We shall be murdered there," said Aramis. "I hate the English - they are so coarse, like all people who drink beer." "Would it be better to remain here?" said Athos. "And take a turn in the Bastille, by the cardinal's order? Believe me, Aramis, there is little left to regret. We avoid imprisonment, and we take the part of heroes - the choice is easy!" While Athos and Aramis were preparing to go to England on behalf of the king, Mazarin had decided to employ D'Artagnan and Porthos as his envoys to Oliver Cromwell. "Monsieur D'Artagnan," said the cardinal, "do you wish to become a captain?" "Yes, my lord." "Your friend wishes to be made a baron?" "At this very moment, my lord, he's dreaming that he is one." "Then," said Mazarin, "take this dispatch, carry it to England, and when you get to London, tear off the outer envelope." "And on our return, may we, my friend and I, rely on getting our promotion - he his barony, I my captaincy?" "On the honour of Mazarin, yes." "I would rather have another sort of oath than that," said D'Artagnan to himself as he went out. Just as they were leaving Paris, a letter came from Athos, who had already gone. "Dear D'Artagnan, dear Porthos, - My friends, perhaps this is the last time you will hear from me. I entrust certain papers which are at Bragelonne to your keeping; if in three months you do not hear of me, take possession of them. May God and the remembrance of our friendship support you always. - Your devoted friend, Athos." Athos and Aramis were with Charles I. at Newcastle. The king had been sold by the Scotch to the English Parliament, and on the approach of Cromwell's army the king's troops refused to fight. Only fifteen men stood round the king when Cromwell's cavalry came charging down. Lord de Winter was shot dead by his own nephew, who was in Cromwell's army. "Come, Aramis, now for the honour of France," said Athos, and the two Englishmen who were nearest to them fell mortally wounded. At the same instant a tremendous shout filled the air, and thirty swords flashed before them. Suddenly a man sprang out of the English ranks, fell upon Athos, wound his muscular arms round him, and tearing his sword from him, said in his ear, "Silence! Yield - you yield to me, don't you?" A giant from the English ranks at the same moment seized Aramis by the wrists, who struggled in vain to get free. "I yield myself prisoner," said Aramis, giving up his sword to Porthos. "D'Art - - " exclaimed Athos; but the musketeer covered his mouth with his hand. The ranks opened. D'Artagnan held the bridle of Athos' horse, and Porthos that of Aramis, and they led their prisoners off the field. "We are all four lost if you give the least sign you know us," said D'Artagnan. "The king - where is the king?" Athos exclaimed anxiously. "Ah! We have got him!" "Yes," said Aramis; "through a base act of treachery!" Porthos pressed his friend's hand, and answered, "Yes; all is fair in war - stratagem as well as force. Look yonder!" The squadron, which ought to have protected the king, was advancing to meet the English regiments. The king, who was entirely surrounded, walked alone on foot. He caught sight of Athos and Aramis, and greeted them. "Farewell, messieurs. The day has been unfortunate, but it is not your fault, thank God! But where is my old friend Winter?" "Look for him with Strafford," said a voice. Charles shuddered. He saw a corpse at his feet. It was Winter's. That hour messengers were sent off in every direction over England and Europe to announce that Charles Stuart was now the prisoner of Oliver Cromwell. D'Artagnan not only accomplished the release of the prisoners, he also joined with his friends in a bold attempt to rescue Charles from his captors. D'Artagnan at first naturally assumed they would all four return to France as quickly as possible; but Athos declared that he could not abandon the king, and still meant to save him if it were possible. "But what can you do in a foreign land; in an enemy's country?" said D'Artagnan. "Did you promise the queen to storm the Tower of London? Come, Porthos, what do you think of this business?" "Nothing good," said Porthos. "Friend," said Athos, "our minds are made up! Ah, if we had you with us! With you, D'Artagnan, and you, Porthos - all four, and reunited for the first time for twenty years - we would dare, not only England but the three kingdoms together!" "Very well," cried D'Artagnan furiously, "very well, since you wish it, let us leave our bones in this horrible land, where it is always cold, where the fine weather comes after a fog, and the fog after rain; in truth, whether we die here or elsewhere matters little, since we must die sooner or later." "But your future career, D'Artagnan? Your ambition, Porthos?" said Athos. "Our future, our ambition!" replied D'Artagnan bitterly. "What do we need to think of that for, if we are to save the king? The king saved, we shall assemble our friends together, reconquer England, and place him securely on the throne." "And he shall make us dukes and peers," said Porthos joyfully at this cheerful prospect. "Or he will forget us," added D'Artagnan. "Then," said Athos, offering his hand to D'Artagnan, "I swear to you, my friend, by the God who hears us, I believe there is a power watching over us, and I look forward to our all meeting in France again." "So be it!" said D'Artagnan; "but I confess I have quite a contrary conviction. However, 'tis settled; but I stay in England only on one condition, that I don't have to learn the language." The attempt to rescue Charles from his guards on the way to London was only frustrated by the sudden arrival of General Harrison, with a large body of soldiers, and D'Artagnan and his friends made their escape by a hasty flight, and followed to London. "We must see this tragedy played out to the end," said Athos. "Do not let us leave England while any hope remains." And the others agreed. The intrepid four were present at the trial of Charles I., and it was the voice of Athos that called out, "You lie!" when the prosecutor declared that the accusation against the king was put forward by the English people. Fortunately, D'Artagnan managed to get Athos out of the court quickly, and then, followed by Porthos and Aramis, they mingled in the crowd outside undetected. Sentence having been pronounced against the king, the only thing to be done by the four was to get rid of the London executioner; this meant at least a few days delay while another executioner was being procured. D'Artagnan undertook this difficult task, while Aramis was to personate Bishop Juxon, the royal chaplain, and explain to Charles the attempt being made to save him. Athos engaged to get everything ready for leaving England. On the very night before the execution Aramis brought the king a message from D'Artagnan, "Tell the king that to-morrow, at ten o'clock at night, we shall carry him off." Aramis added, "He has said it, and he will do it." The scaffold was already being constructed in Whitehall as he spoke, but D'Artagnan had the London executioner fast bound under lock and key in a cellar, and Athos had a light skiff waiting at Greenwich. Not only this, but at midnight these four wonderful men, thanks to Athos, who spoke excellent English, were also at work at the scaffold - having bribed the carpenter in charge to let them assist - and at the same time boring a hole in the wall. The scaffold, which had two lower stories, and was covered with black serge, was at the height of twenty feet, on a level with the window in the king's room; and the hole communicated with a narrow loft, between the floor of the king's room, and the ceiling of the one below it. The plan was to pass through the hole into the loft, and cut out from below a piece of the flooring of the king's room, so as to form a kind of trap-door. The king was to escape through this on the following night, and, hidden by the black covering of the scaffold, was then to change his dress for that of a workman, and so pass the sentinels on duty, and reach the skiff that was waiting for him at Greenwich. At nine o'clock in the morning Aramis, this time in attendance on Bishop Juxon, was once more in the king's room. "Sire," he said, "you are saved! The London executioner has vanished, and there is no executioner nearer at hand than Bristol. The Count de la Fère is two feet below you; take the poker from the fireplace, and strike three times on the floor. He will answer you. He has the path ready for your majesty to escape by." The king did as Aramis suggested, and in reply came three dull knocks from below. "The Count de la Fère," said Aramis. All was ready; nothing as far as D'Artagnan and Athos could see, had been overlooked; twenty-four hours hence would see the king beyond the reach of his adversaries. And then just as Charles had satisfied himself that his life was saved, a Parliamentary officer and a file of soldiers entered the king's room to announce his immediate execution. "Then it is for to-day?" asked the king. "Were not you warned that it was to take place this morning?" "Then I must die like a common criminal by the hand of the London executioner?" "The London executioner has disappeared, but a man has offered his services instead. The execution will, therefore, take place at the appointed hour." A fanatical Puritan, nephew of Lord de Winter - whom he slew at Newcastle - and a trusted lieutenant of Cromwell's did the work of the headsman, and upon Athos, waiting in concealment beneath the scaffold, fell drops of the king's blood. When all was over the four hastened away in deep dejection to the skiff at Greenwich, and so to France. But when they had landed at Dunkirk it was plain to D'Artagnan that their troubles were not yet at an end. "Porthos and I were sent by Cardinal Mazarin to fight for Cromwell; instead of fighting for Cromwell, we have served Charles I.; that's not the same thing at all." However, D'Artagnan and Porthos, on their return to Paris, rendered such signal service to Mazarin and to the queen, by guarding them from the violence of the mob, and by quelling a riot, that D'Artagnan received his commission as captain of musketeers, and Porthos his barony. The four old friends met once more in Paris before they separated. Aramis was returning to his convent, Athos and Porthos to their estates. As war had just broken out in Flanders, D'Artagnan made ready to go thither. Then all four embraced, with tears in their eyes. And after that they departed on their various ways, not knowing whether they were ever to see each other again. |