|

|

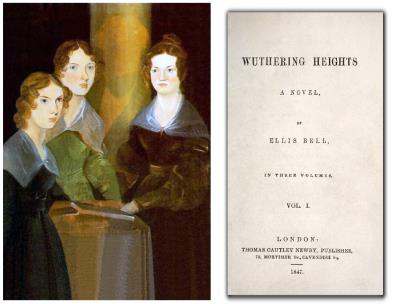

by Emily (Jane) Brontë The original, squashed down to read in about 30 minutes  Anne, Emily, and Charlotte Brontë, painted by their brother Branwell. (London, 1847) Here is Emily Brontë's only novel, published in 1847 under the pseudonym Ellis Bell. The story of the all-encompassing, passionate, and thwarted, love between Heathcliff and Catherine Earnshaw is considered a classic of English literature, and has given rise to many adaptations and inspired works, including films, radio, television dramatisations, a musical, songs, notably by Kate Bush, ballet and opera. Abridged: JH/GH For more works by the Brontës, see The Index 1801 - I have just returned from a visit to my landlord - the solitary neighbour that I shall be troubled with in this beautiful country! He little imagined how my heart warmed towards him when I beheld his black eyes withdraw so suspiciously under their brows, as I rode up; "Mr. Heathcliff?" A nod was the answer. "Mr. Lockwood, your new tenant at Thrushcross Grange, sir." "Walk in." But the invitation, uttered with closed teeth, expressed the sentiment "Go to the deuce!" And it was not till my horse's breast fairly pushed the barrier that he put out his hand to unchain it. I felt interested in a man who seemed more exaggeratedly reserved than myself as he preceded me up the causeway, calling, "Joseph, take Mr. Lockwood's horse; and bring up some wine." Joseph was an old man, very old, though hale and sinewy. "The Lord help us!" he soliloquised in an undertone as he relieved me of my horse. Wuthering Heights, Mr. Heathcliff's dwelling, is a farmhouse on an exposed and stormy edge, its name being a provincial adjective of atmospheric tumult. Its owner is a dark-skinned gipsy in aspect, in dress and manners a gentleman, with erect and handsome figure, but morose demeanour. One step from the outside brought us into the family living-room, the recesses of which were haunted by a huge liver-coloured bitch pointer, with a swarm of squealing puppies, and other dogs. As the bitch sneaked wolfishly to the back of my legs I attempted to caress her, an action that provoked a long, guttural growl. "You'd better let the dog alone," growled Mr. Heathcliff in unison, as he checked her with a punch of his foot. "She's not accustomed to be spoiled." As Joseph was mumbling indistinctly in the depths of the cellar, and gave no sign of ascending, his master dived down to him, leaving me vis-a-vis with the ruffianly bitch and half a dozen four-footed fiends that suddenly broke into a fury, while I parried off the attack with a poker and called aloud for assistance. "What the devil is the matter?" asked Heathcliff, as he returned. "What the devil, indeed!" I muttered. "You might as well leave a stranger with a brood of tigers!" "They won't meddle with persons who touch nothing," he remarked. "The dogs are right to be vigilant. Take a glass of wine." Before I went home I determined to volunteer another visit to my sulky landlord, though evidently he wished for no repetition of my intrusion. Yesterday I again visited Wuthering Heights, my nearest neighbours to Thrushcross Grange. On that bleak hill-top the earth was hard with a black frost, and the air made me shiver through every limb. As I knocked for admittance, till my knuckles tingled and the dogs howled, vinegar- faced Joseph projected his head from a round window of the barn, and shouted to me. "What are ye for? T'maister's down i' t' fowld. There's nobbut t' missis. I'll hae no hend wi't," muttered the head, vanishing. Then a young man, without coat and shouldering a pitchfork, hailed me to follow him, and showed me into the apartment where I had been formerly received with a gruff "Sit down; he'll be in soon." In the room sat the "missis," motionless and mute. She was slender, scarcely past girlhood, with the most exquisite little face I have ever had the pleasure of beholding; and her eyes, had they been agreeable in expression, would have been irresistible. But the only sentiment they evinced hovered between scorn and a kind of desperation. As for the young man who had brought me in, he slung on his person a shabby jacket, and, erecting himself before the fire, gazed down on me from the corner of his eyes as if there was some mortal feud unavenged between us. The entrance of Heathcliff relieved me from an uncomfortable state. I found in the course of the tea which followed that the lady was the widow of Heathcliff's son, and that the rustic youth who sat down to the meal with us was Hareton Earnshaw. Now, before passing the threshold, I had noticed over the principal door, among a wilderness of crumbling griffins and shameless little boys, the name "Hareton Earnshaw" and the date "1500." Evidently the place had a history. The snow had fallen so deeply since I entered the house that return across the moor in the dusk was impossible. Spending that night at Wuthering Heights on an old-fashioned couch that filled a recess, or closet, in a disused chamber, I found, scratched on the paint many times, the names "Catherine Earnshaw," "Catherine Heathcliff," and again "Catherine Linton." There were many books in the room in a dilapidated state, and, being unable to sleep, I examined them. Some of them bore the inscription "Catherine Earnshaw, her book"; and on the blank leaves and margins, scrawled in a childish hand, was a regular diary. I read: "Hindley is detestable. Heathcliff and I are going to rebel.... How little did I dream Hindley would ever make me cry so! Poor Heathcliff! Hindley calls him a vagabond, and won't let him sit or eat with us any more." When I slept I was harrowed by nightmare, and next morning I gladly left the house; and, piloted by my landlord across the billowy white ocean of the moor, I reached the Grange benumbed with cold and as feeble as a kitten from fatigue. When my housekeeper, Mrs. Nelly Dean, brought in my supper that night I asked her why Heathcliff let the Grange and preferred living in a residence so much inferior. "He's rich enough to live in a finer house than this," said Mrs. Dean; "but he's very close-handed. Young Mrs. Heathcliff is my late master's daughter- Catherine Linton was her maiden name, and I nursed her, poor thing. Hareton Earnshaw is her cousin, and the last of an old family." "The master, Heathcliff, must have had some ups and downs to make him such a churl. Do you know anything of his history?" "It's a cuckoo's, sir. I know all about it, except where he was born, and who were his parents, and how he got his money. And Hareton Earnshaw has been cast out like an unfledged dunnock." I asked Mrs. Dean to bring her sewing, and continue the story. This she did, evidently pleased to find me companionable. Before I came to live here (began Mrs. Dean), I was almost always at Wuthering Heights, because my mother nursed Mr. Hindley Earnshaw, that was Hareton's father, and I used to run errands and play with the children. One day, old Mr. Earnshaw, Hareton's grandfather, went to Liverpool, and promised Hindley and Cathy, his son and daughter, to bring each of them a present. He was absent three days, and at the end of that time brought home, bundled up in his arms under his great-coat, a dirty, ragged, black-haired child, big enough both to walk and talk, but only able to talk gibberish nobody could understand. He had picked it up, he said, starving and homeless in the streets of Liverpool. Mrs. Earnshaw was ready to fling it out of doors, but Mr. Earnshaw told her to wash it, give it clean things, and let it sleep with the children. The children's presents were forgotten. This was how Heathcliff, as they called him, came to Wuthering Heights. Miss Cathy and he soon became very thick; but Hindley hated him. He was a patient, sullen child, who would stand blows without winking or shedding a tear. From the beginning he bred bad feeling in the house. Old Earnshaw took to him strangely, and Hindley regarded him as having usurped his father's affections. As for Heathcliff, he was insensible to kindness. Cathy, a wild slip, with the bonniest eye, the sweetest smile, and the lightest foot in the parish, was much too fond of Heathcliff. Old Mr. Earnshaw died quietly in his chair by the fireside one October evening. Mr. Hindley, who had been to college, came home to the funeral, and set the neighbours gossiping right and left, for he brought a wife with him. What she was and where she was born he never informed us. She evinced a dislike to Heathcliff, and drove him to the company of the servants, but Cathy clung to him, and the two promised to grow up together as rude as savages. Once Hindley shut them out for the night and they came to Thrushcross Grange, where the Lintons took Cathy in, but would not have anything to do with Heathcliff, the Spanish castaway, as they called him. She stayed five weeks with the Lintons, and became very friendly with the children, Edgar and Isabella, and when she came back was a dignified little person, and quite a beauty. Soon after, Hindley's son, Hareton, was born, the mother died, and the child fell wholly into my hands, for the father grew desperate in his sorrow, and gave himself up to reckless dissipation. His treatment of Heathcliff now was enough to make a fiend of a saint, and daily the lad became more savagely sullen. I could not half-tell what an infernal house we had, till at last nobody decent came near us, except that Edgar Linton called to see Cathy, who at fifteen was the queen of the countryside- a haughty and headstrong creature. One day after Edgar Linton had been over from the Grange, Cathy came into the kitchen to me and said, "Nelly, will you keep a secret for me? To-day Edgar Linton has asked me to marry him, and I've given him an answer. I accepted him, Nelly. Be quick and say whether I was wrong." "First and foremost," I said sententiously, "do you love Mr. Edgar?" "I love the ground under his feet, and the air over his head, and everything he touches, and every word he says. I love his looks, and all his actions, and him entirely and altogether. There now!" "Then," said I, "all seems smooth and easy. Where is the obstacle?" "Here, and here!" replied Catherine, striking one hand on her forehead, and the other on her breast. "In my soul and in my heart I'm convinced I'm wrong! I've no more business to marry Edgar Linton than I have to be in heaven; and if the wicked man in there, my brother, had not brought Heathcliff so low I shouldn't have thought of it. It would degrade me to marry Heathcliff now; so he shall never know how I love him, and that not because he's handsome, Nelly, but because he's more myself than I am. Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same, and Linton's is as different as a moonbeam from lightning, or frost from fire. Nelly, I dreamed I was in heaven, but heaven did not seem to be my home, and I broke my heart with weeping to come back to earth; and the angels were so angry that they flung me out into the middle of the heath on the top of Wuthering Heights, where I woke sobbing for joy." Ere this speech was ended, Heathcliff, who had been lying out of sight on a bench by the kitchen wall, stole out. He had heard Catherine say it would degrade her to marry him, and he had heard no further. That night, while a storm rattled over the heights in full fury, Heathcliff disappeared. Catherine suffered uncontrollable grief, and became dangerously ill. When she was convalescent she went to Thrushcross Grange. But Edgar Linton, when he married her, three years subsequent to his father's death, and brought her here to the Grange, was the happiest man alive. I accompanied her, leaving little Hareton, who was now nearly five years old, and had just begun to learn his letters. On a mellow evening in September, I was coming from the garden with a basket of apples I had been gathering, when, as I approached the kitchen door, I heard a voice say, "Nelly, is that you?" Something stirred in the porch, and, moving nearer, I saw a tall man, dressed in dark clothes, with dark hair and face. "What," I cried, "you come back?" "Yes, Nelly. You needn't be so disturbed. I want one word with your mistress." I went in, and explained to Mr. Edgar and Catherine who was waiting below. "Oh, Edgar darling," she panted, flinging her arms round his neck, "Heathcliff's come back- he is!" "Well, well," he said, "don't strangle me for that. There's no need to be frantic. Try to be glad without being absurd!" When Heathcliff came in, she seized his hands and laughed like one beside herself. It seemed that he was staying at Wuthering Heights, invited by Mr. Earnshaw! When I heard this I had a presentiment that he had better have remained away. Later, we learned from Joseph that Heathcliff had called on Earnshaw, whom he found sitting at cards, had joined in the play, and, seeming plentifully supplied with money, had been asked by his ancient persecutor to come again in the evening. He then offered liberal payment for permission to lodge at the Heights, which Earnshaw's covetousness made him accept. Heathcliff now commenced visiting Thrushcross Grange, and gradually established his right to be expected. A new source of trouble sprang up in an unexpected form-Isabella Linton evincing a sudden and irresistible attraction towards Heathcliff. At that time she was a charming young lady of eighteen. I tried to persuade her to banish him from her thoughts. "He's a bird of bad omen, miss," I said, "and no mate for you. How has he been living? How has he got rich? Why is he staying at Wuthering Heights in the house of the man whom he abhors? They say Mr. Earnshaw is worse and worse since he came. They sit up all night together continually, and Hindley has been borrowing money on his land, and does nothing but play and drink." "You are leagued with the rest," she replied, "and I'll not listen to your slanders." The antipathy of Mr. Linton towards Heathcliff reached a point at last at which he called on his servants one day to turn him out of the Grange, whereupon Heathcliff's revenge took the form of an elopement with Linton's sister. Six weeks later I received a letter of bitter regret from Isabella, asking me distractedly whether I thought her husband was a man or a devil, and how I had preserved the common sympathies of human nature at Wuthering Heights, where they had returned. On receiving this letter, I obtained permission from Mr. Linton to go to the Heights to see his sister, and Heathcliff, on meeting me, urged me to secure for him an interview with Catherine. "Nelly," said he, "you know as well as I do that for every thought she spends on Linton she spends a thousand on me. If he loved her with all the powers of his puny being, he couldn't love as much in eighty years as I could in a day. And Catherine has a heart as deep as I have. The sea could be as readily contained in that horse-trough as her whole affection be monopolised by him." Well, I argued, and refused, but in the long run he forced me to agree to put a missive into Mrs. Linton's hand. When he met her, I saw that he could hardly bear, for downright agony, to look into her face, for he was stricken with the conviction that she was fated to die. "Oh, Cathy, how can I bear it?" was the first sentence he uttered. "You and Edgar have broken my heart, Heathcliff," was her reply. "You have killed me and thriven on it, I think." "Are you possessed with a devil," he asked, "to talk in that manner to me when you are dying? You know you lie to say I have killed you, and you know that I could as soon forget my existence as forget you. Is it not sufficient that while you are at peace, I shall be in the torments of hell?" "I shall not be at peace," moaned Catherine. "Why did you despise me? Why did you betray your own heart? You loved me. What right had you to leave me?" "Let me alone!" sobbed Catherine. "I've done wrong, and I'm dying for it! Forgive me!" That night was born the Catherine you, Mr. Lockwood, saw at the Heights, and her mother's spirit was at home with God. When in the morning I told Heathcliff, who had been watching near all night, he dashed his head against the knotted trunk of the tree by which he stood and howled, not like a man, but like a savage beast, as he besought her ghost to haunt him. "Be with me always-take any form!" he cried. "Only do not leave me in this abyss, where I cannot find you!" Life with Heathcliff becoming impossible to Isabella, she left the neighbourhood, never to revisit it, and lived near London; and there her son, whom she christened Linton, was born a few months after her escape. He was an ailing, peevish creature. When Linton was twelve, or a little more, and Catherine thirteen, Isabella died, and the boy was brought to Thrushcross Grange. Hindley Earnshaw drank himself to death about the same time, after mortgaging every yard of his land for cash; and Heathcliff was the mortgagee. So Hareton Earnshaw, who should have been the first gentleman in the neighbourhood, was reduced to dependence on his father's enemy, in whose house he lived, ignorant that he had been wronged. The motives of Heathcliff now became clear. Under the influence of a passionate but calculating revenge, allied with greed, he was planning the destruction of the Earnshaw family, and the union of the Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange estates. To this end, having brought his weakly son home to the Heights and terrorised him into a pitiable slavery, he schemed a marriage between him and young Catherine Linton, who was induced to accept the arrangement through sympathy with her cousin, and the hope of removing him from the paralysing influence of his father. The marriage was almost immediately followed by the death of both Catherine's father and her boyish husband, who, it was afterwards found, had been coaxed or threatened into bequeathing all his property to his father. Thus ended Mrs. Dean's story of how the strangely assorted occupants of Wuthering Heights had come together, my landlord Heathcliff, the disinherited, poor Hareton Earnshaw, and Catherine Heathcliff, who had been Catherine Linton and the daughter of Catherine Earnshaw. I propose riding over to Wuthering Heights to inform my landlord that I shall spend the next six months in London, and that he may look out for another tenant for the Grange. Yesterday was bright, calm, and frosty, and I went to the Heights as I proposed. My housekeeper entreated me to bear a little note from her to her young lady, and I did not refuse, for the worthy woman was not conscious of anything odd in her request. Hareton Earnshaw unchained the gate for me. The fellow is as handsome a rustic as need be seen, but he does his best, apparently, to make the least of his advantages. Catherine, who was preparing vegetables for a meal, looked more sulky and less spirited than when I had seen her first. "She does not seem so amiable," I thought, "as Mrs. Dean would persuade me to believe. She's a beauty, it is true, but not an angel." I approached her, pretending to desire a view of the garden, and dropped Mrs. Dean's note on her knee unnoticed by Hareton. But she asked aloud, "What is that?" and chucked it off. "A letter from your old acquaintance, the housekeeper at the Grange," I answered. She would gladly have gathered it up at this information, but Hareton beat her. He seized and put it in his waistcoat, saying Mr. Heathcliff should look at it first; but later he pulled out the letter, and flung it on the floor as ungraciously as he could. Catherine perused it eagerly, and then asked, "Does Ellen like you?" "Yes, very well," I replied hesitatingly. Whereupon she became more communicative, and told me how dull she was now Heathcliff had taken her books away. When Heathcliff came in, looking restless and anxious, he sent her to the kitchen to get her dinner with Joseph; and with the master of the house, grim and saturnine, and Hareton absolutely dumb, I made a cheerless meal, and bade adieu early. Next September, when going north for shooting, a sudden impulse seized me to visit Thrushcross Grange and pass a night under my own roof, for the tenancy had not yet expired. When I reached the Grange before sunset I found a girl knitting under the porch, and an old woman reclining on the house-steps, smoking a meditative pipe. "Is Mrs. Dean within?" I demanded. "Mistress Dean? Nay!" she answered. "She doesn't bide here; shoo's up at th' Heights." "Are you housekeeper, then?" "Eea, aw keep th' house," she replied. "Well, I'm Mr. Lockwood, the master. Are there any rooms to lodge me in, I wonder? I wish to stay all night." "T' maister!" she cried in astonishment. "Yah sud ha' sent word. They's nowt norther dry nor mensful abaht t' place!" Leaving her scurrying about making preparations, I climbed the stony by-road that branches off to Mr. Heathcliff's dwelling. On reaching it I had neither to climb the gate nor to knock-it yielded to my hand. "This is an improvement," I thought. I noticed, too, a fragrance of flowers wafted on the air from among the homely fruit-trees. "Con-trary!" said a voice as sweet as a silver bell "That for the third time, you dunce! I'm not going to tell you again." "Contrary, then," answered another in deep but softened tones. "And now kiss me for minding so well." The male speaker was a young man, respectably dressed and seated at a table, having a book before him. His handsome features glowed with pleasure, and his eyes kept impatiently wandering from the page to a small white hand over his shoulder. So, not to interrupt Hareton Earnshaw and Catherine Heathcliff, I went round to the kitchen, where my old friend Nelly Dean sat sewing and singing a song. Mrs. Dean jumped to her feet as she recognised me. "Why, bless you, Mr. Lockwood!" she exclaimed. "Pray step in! Have you walked from Gimmerton?" "No, from the Grange," I replied; "and while they make me a lodging room there I want to finish my business with your master." "What business, sir?" said Nelly. "About the rent," I answered. "Oh, then it is Catherine you must settle with, or rather me, as she has not learned to arrange her affairs yet." I looked surprised. "Ah! You have not heard of Heathcliff's death, I see," she continued. "Heathcliff dead!" I exclaimed. "How long ago?" "Three months since; but sit down, and I'll tell you all about it." "I was summoned to Wuthering Heights," she said, "within a fortnight of your leaving us, and I went gladly for Catherine's sake. Mr. Heathcliff, who grew more and more disinclined to society, almost banished Earnshaw from his apartment, and was tired of seeing Catherine-that was the reason why I was sent for-and the two young people were thrown perforce much in each other's company in the house, and presently Catherine began to make it clear to her obstinate cousin that she wished to be friends. The intimacy ripened rapidly, and, Mr. Lockwood, on their wedding day there won't be a happier woman in England than myself. Joseph was the only objector, and he appealed to Heathcliff against 'yon flaysome graceless quean, that's witched our lad wi' her bold een and her forrad ways.' But after a burst of passion at the news, Mr. Heathcliff suddenly calmed down and said to me, 'Nelly, there is a strange change approaching; I'm in its shadow.' "Soon after that he took to wandering alone, in a state approaching distraction. He could not rest; he could not eat; and he would not see the doctor. One morning as I walked round the house I observed the master's window swinging open and the rain driving straight in. 'He cannot be in bed,' I thought, 'those showers would drench him through.' And so it was, for when I entered the chamber his face and throat were washed with rain, the bed-clothes dripped, and he was perfectly still- dead and stark. I called up Joseph. 'Eh, what a wicked 'un he looks, girning at death,' exclaimed the old man, and then he fell on his knees and returned thanks that the ancient Earnshaw stock were restored to their rights. "I shall be glad when they leave the Heights for the Grange," concluded Mrs. Dean. "They are going to the Grange, then?" "Yes, as soon as they are married; and that will be on New Year's Day." My walk home was lengthened by a diversion in the direction of the kirk. I sought, and soon discovered, three headstones on the slope next the moor: on middle one grey, and half buried in the heath; Edgar Linton's only harmonized by the turf and moss creeping up its foot; Heathcliff"s still bare. I lingered round them, under that benign sky: watched the moths fluttering among the heath and harebells, listened to the soft wind breathing through the grass, and wondered how any one could ever imagine unquiet slumbers for the sleepers in that quiet earth. |