|

|

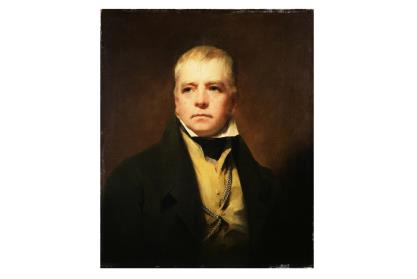

by Walter Scott The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (1818) Walter Scott (1771-1832) was a law-clerk and judge, Clerk of Session and Sheriff-Depute of Selkirkshire, one of the leading figures of Scottish Toryism and of the Highland Society. Scott was the first English-language author to achieve international fame, largely with novels of a romantic past. Abridged: JH For more works by Walter Scott, see The Index I. - In the Tolbooth In former times England had her Tyburn, to which the devoted victims of justice were conducted in solemn procession; and in Edinburgh, a large oblong square, called the Grassmarket, was used for the same purpose. This place was crowded to suffocation on the day when John Porteous, captain of the City Guard, was to be hanged, sentenced to death for firing on the crowd on the occasion of the execution of a popular smuggler. The grim appearance of the populace conveyed the impression of men who had come to glut their sight with triumphant revenge. When the news that Porteous was respited for six weeks was announced, a roar of rage and mortification arose, but speedily subsided into stifled mutterings as the people slowly dispersed. That night the mob broke into the Tolbooth, the prison, commonly called the Heart of Midlothian, dragged the wretched Porteous from the chimney in which he had concealed himself, and carried him off to the Grassmarket, where, as the leader of the rioters, a tall man dressed in woman's clothes said he had spilled the blood of so many innocents. "Let no man hurt him," continued the speaker. "Let him make his peace with God, if he can; we will not kill both soul and body." A young minister named Butler, whom the rioters had met and compelled to come with them, was brought to the prisoner's side, to prepare him for instant death. With a generous disregard of his own safety, Butler besought the crowd to consider what they did. But in vain. The unhappy man was forced to his fate with remorseless rapidity, and Butler, separated from him by the press, and unnoticed by those who had hitherto kept him prisoner, escaped the last horror, and fled from the fatal spot. His first purpose was instantly to take the road homewards, but other fears and cares, connected with news he had that day heard, induced him to linger till daybreak. Reuben Butler was the grandson of a trooper in Monk's army, and had been brought up by a grandmother, a widow, a cotter who struggled with poverty and the hard and sterile soil on the land of the Laird of Dumbiedikes. She was helped by the advice of another tenant, David Deans, a staunch Presbyterian, and Jeannie, his little daughter, and Reuben herded together the handful of sheep and the two or three cows, and went together to the school; where Reuben, as much superior to Jeannie Deans in acuteness of intellect as inferior to her in firmness of constitution, was able to requite in full the kindness and countenance with which, in other circumstances, she used to regard him. While Reuben Butler was acquiring at the university the knowledge necessary for a clergyman, David Deans, by shrewdness and skill, gained a footing in the world and the possession of some wealth. He had married again, and another daughter had been born to him. But now his wife was dead, and he had left his old home, and become a dairy farmer about half a mile from Edinburgh, and the unceasing industry and activity of Jeannie was exerted in making the most of the produce of their cows. Effie, his youngest daughter, under the tend guileless purity of thought, speech, and action, as by her uncommon loveliness of person. The news that this girl was in prison on suspicion of the murder of her child was what kept Reuben Butler lingering on the hills outside Edinburgh, until a fitting time should arrive to wait upon Jeannie and her father. Effie denied all guilt of infanticide; but she had concealed the birth of a child, and the child had disappeared, so that by the law she was judged guilty. His limbs exhausted with fatigue, Butler dragged himself up to St. Leonard's crags, and presented himself at the door of Deans' habitation, with feelings much akin to the miserable fears of its inhabitants. "Come in," answered the low, sweet-toned voice he loved best to hear, as he tapped at the door. The old man was seated by the fire with his well-worn pocket Bible in his hands, and turned his face away as Butler entered and clasped the extended hand which had supported his orphan infancy, wept over it, and in vain endeavoured to say more than "God comfort you! God comfort you!" "He will - He doth, my friend," said Deans. "He doth now, and He will yet more in His own gude time. I have been ower proud of my sufferings in a gude cause, Reuben, and now I am to be tried with those whilk will turn my pride and glory into a reproach and a hissing." Butler had too much humanity to do anything but encourage the good old man as he reckoned up with conscious pride the constancy of his testimony and his sufferings, but seized the opportunity as soon as possible of some private conversation with Jeannie. He gave her the message he had received from a stranger he had met an hour or two before, to the effect that she must meet him that night alone at Muschat's cairn at moonrise. "Tell him," said Jeannie hastily, "I will certainly come"; and to all Butler's entreaties and expostulations would give no explanation. They were recalled - "ben the house," to use the language of the country - by the loud tones of David Deans, and found the poor old man half frantic between grief and zealous ire against proposals to employ a lawyer on Effie's behalf, they being, all, in his opinion, carnal, crafty self-seekers. But when the poor old man, fatigued with the arguments and presence of his guests, retired to his sleeping apartment, the Laird of Dumbiedikes said he would employ his own man of business, and Butler set off instantly to see Effie herself, and try to get her to give him the information that she had refused to everyone. "Farewell, Jeannie," said he. "Take no rash steps till you hear from me." Butler was at once recognised by the turnkey when he presented himself at the Tolbooth, and detained as having been connected with the riots the night before. One of the prisoners had recognised Robertson, the leader of the rioters, and seen him trying to persuade Effie Deans to escape and to save himself from the gallows, being a well-known thief and prison-breaker, gave information, hoping, as he candidly said, to obtain the post of gaoler himself. It became obvious that the father of Effie's child and the slayer of Porteous were one and the same person, and on hearing from Butler, who had no reason to conceal his movements, of the stranger he had met on the hill, the procurator fiscal, otherwise the superintendent of police, with a strong body-guard, interrupted Jeannie's meeting with the stranger that night; but he had made her understand that her sister's life was in her hands before, hearing men approaching, he plunged into the darkness and was lost to sight. II. - Effie's Trial Soon afterwards, Ratcliffe, the prisoner who had recognised Robertson, received a full pardon, and becoming gaoler, was repeatedly applied to, to procure an interview between the sisters; but the magistrates had given strict orders to the contrary, hoping that they might, by keeping them apart, obtain some information respecting the fugitive. But Jeannie knew nothing of Robertson, except having met him that night by appointment to give her some advice respecting her sister's concern, the which, she said, was betwixt God and her conscience. And Effie was equally silent. In vain they offered, even a free pardon, if she would confess what she knew of her lover. At length the day was fixed for Effie's trial, and on the preceding evening Jeannie was allowed to see her sister. Even the hard-hearted turnkey could not witness the scene without a touch of human sympathy. "Ye are ill, Effie," were the first words Jeannie could utter. "Ye are very ill." "O, what wad I gie to be ten times waur, Jeannie!" was the reply. "O that I were lying dead at my mother's side!" "Hout, lassie!" said Ratcliffe. "Dinna be sae dooms downhearted as a' that. There's mony a tod hunted that's no killed. They are weel aff has such a counsel and agent as ye have; ane's aye sure of fair play." But the mourners had become unconscious of his presence. "O Effie," said her elder sister, "how could you conceal your situation from me? O woman, had I deserved this at your hand? Had ye but spoke ae word - - " "What gude wad that hae dune?" said the prisoner. "Na, na, Jeannie; a' was ower whan once I forgot what I promised when I turned down the leaf of my Bible. See, the Book aye opens at the place itsell. O see, Jeannie, what a fearfu' Scripture!" "O if ye had spoken ae word again!" sobbed Jeannie. "If I were free to swear that ye had said but ae word of how it stude wi' you, they couldna hae touched your life this day!" "Could they na?" said Effie, with something like awakened interest. "Wha' tauld ye that, Jeannie?" "It was ane that kenned what he was saying weel eneugh," said Jeannie. "Hout!" said Ratcliffe. "What signifies keeping the poor lassie in a swither? I'se uphand it's been Robertson that learned ye that doctrine." "Was it him?" cried Effie. "Was it him, indeed? O I see it was him, poor lad! And I was thinking his heart was as hard as the nether millstane, and him in sic danger on his ain part. Poor George! O, Jeannie, tell me every word he said, and if he was sorry for poor Effie!" "What needs I tell ye onything about 't?" said Jeannie. "Ye may be sure he had ower muckle about onybody beside." "That's no' true, Jeannie, though a saint had said it," replied Effie. "But ye dinna ken, though I do, how far he put his life in venture to save mine." And looking at Ratcliffe, checked herself and was silent. "I fancy," said he, "the lassie thinks naebody has een but hersell. Didna I see Gentle Geordie trying to get other folk out of the Tolbooth forbye Jock Porteous? Ye needna look sae amazed. I ken mair things than that, maybe." "O my God, my God!" said she, throwing herself on her knees before him. "D'ye ken where they hae putten my bairn? O my bairn, my bairn! Tell me wha has taen't away, or what they hae dune wi't!" As his answer destroyed the wild hope that had suddenly dawned upon her, the unhappy prisoner fell on the floor in a strong convulsion fit. Jeannie instantly applied herself to her sister's relief, and Ratcliffe had even the delicacy to withdraw to the other end of the room to render his official attendance as little intrusive as possible; while Jeannie commenced her narrative of all that had passed between her and Robertson. After a long pause: "And he wanted you to say something to you folks that wad save my young life?" said Effie. "He wanted," said Jeannie, "that I shuld be mansworn!" "And you tauld him," said Effie, "that ye wadna hear o' coming between me and death, and me no aughteen year auld yet?" "I dinna deserve this frae ye, Effie," said her sister, feeling the injustice of the reproach and compassion for the state of mind which dictated it. "Maybe no, sister," said Effie. "But ye are angry because I love Robertson. Sure am I, if it had stude wi' him as it stands wi' you - - " "O if it stude wi' me to save ye wi' the risk of my life!" said Jeannie. "Ay, lass," said her sister, "that's lightly said, but no sae lightly credited frae ane that winna ware a word for me; and if it be a wrang word, ye'll hae time enough to repent o' 't." "But that word is a grievous sin." "Well, weel, Jeannie, never speak mair o' 't," said the prisoner. "It's as weel as it is. And gude-day, sister. Ye keep Mr. Ratcliffe waiting on. Ye'll come back and see me, I reckon, before - - " "And are we to part in this way," said Jeannie, "and you in sic deadly peril? O, Effie, look but up and say what ye wad hae me do, and I could find it in my heart amaist to say I wad do 't." "No, Jeannie," said her sister, with an effort. "I'm better minded now. God knows, in my sober mind, I wadna' wuss any living creature to do a wrang thing to save my life!" But when Jeannie was called to give her evidence next day, Effie, her whole expression altered to imploring, almost ecstatic earnestness of entreaty, exclaimed, in a tone that went through all hearts: "O Jeannie, Jeannie, save me, save me!" Jeannie suddenly extended her hand to her sister, who covered it with kisses and bathed it with tears; while Jeannie wept bitterly. It was some time before the judge himself could subdue his own emotion and administer the oath: "The truth to tell, and no truth to conceal, in the name of God, and as the witness should answer to God at the great Day of Judgement." Jeannie, educated in devout reverence for the name of the Deity, was awed, but at the same time elevated above all considerations save those to which she could, with a clear conscience, call him to witness. Therefore, though she turned deadly pale, and though the counsel took every means to make it easy for her to bear false witness, she replied to his question as to what Effie had said when questioned as to what ailed her, "Alack! alack! she never breathed a word to me about it." A deep groan passed through the court, and the unfortunate father fell forward, senseless. The secret hope to which he had clung had now dissolved. The prisoner with impotent passion, strove with her guard. "Let me gang to my father! He is dead! I hae killed him!" she repeated in frenzied tones. Even in that moment of agony Jeannie did not lose that superiority that a deep and firm mind assures to its possessor. She stooped, and began assiduously to chafe her father's temples. The judge, after repeatedly wiping his eyes, gave directions that they should be removed and carefully attended. The prisoner pursued them with her eyes, and when they were no longer visible, seemed to find courage in her despair. "The bitterness of 't is now past," she said. "My lords, if it is your pleasure to gang on wi' this matter, the weariest day will have its end at last." III. - Jeannie's Pilgrimage David Deans and his eldest daughter found in the house of a cousin the nearest place of friendly refuge. When he recovered from his long swoon, he was too feeble to speak when their hostess came in. "Is all over?" said Jeannie, with lips pale as ashes. "And is there no hope for her?" "Nane, or next to nane," said her cousin, Mrs. Saddletree; but added that the foreman of the jury had wished her to get the king's mercy, and "nae ma about it." "But can the king gie her mercy?" said Jeannie. "I well he wot he can, when he likes," said her cousin and gave instances, finishing with Porteous. "Porteous," said Jeannie, "very true. I forgot a' that I culd mind maist. Fare ye well, Mrs. Saddletree. May ye never want a friend in the hour o' distress." To Mrs. Saddletree's protests she replied there was much to be done and little time to do it in; then, kneeling by her father's bed, begged his blessing. Instinctively the old man murmured a prayer, and his daughter saying, "He has blessed mine errand; it is borne in on my mind that I shall prosper," left the room. Mrs. Saddletree looked after her, and shook her head. "I wish she binna roving, poor thing. There's something queer about a' thae Deanes. I dinna like folk to be sae muckle better than ither folk; seldom comes gude o't." But she took good care of "the honest auld man," until he was able to go to his own home. Effie was roused from her state of stupefied horror by the entrance of Jeannie who, rushing into the cell, threw her arms round her neck. "What signifies coming to greet ower me," said poor Effie, "when you have killed me? Killed me, when a word from your mouth would have saved me." "You shall not die," said Jeannie, with enthusiastic firmness. "Say what you like o' me, only promise, for I doubt your proud heart, that you winna' harm yourself? I will go to London and beg your pardon from the king and queen. They shall pardon you, and they will win a thousand hearts by it!" She soon tore herself from her sister's arms and left the cell. Ratcliffe followed her, so impressed was he by her "spunk," he advised her as to her proceedings, to find a friend to speak for her to the king - the Duke of Argyle, if possible - and wrote her a line or two on a dirty piece of paper, which would be useful if she fell among thieves. Jeannie then hastened home to St. Leonard's Crags, and gave full instructions to her usual assistant, concerning the management of domestic affairs and arrangements for her father's comfort in her absence. She got a loan of money from the Laird of Dumbiedikes, and set off without losing a moment on her walk to London. On her way she stopped to bid adieu to her old friend Reuben Butler, whom she had expected to see at the court yesterday. She knew, of course, that he was still under some degree of restraint - he had been obliged to find bail not to quit his usual residence, in case he were wanted as a witness-but she had hoped he would have found means to be with his old friend on such a day. She found him quite seriously ill, as she had feared, but yet most unwilling to let her go on this errand alone; she must give him a husband's right to protect her. But she, pointing out the fact that he was scarcely able to stand, said this was no time to speak of marrying or giving in marriage, asked him if his grandfather had not done some good to the forebear of MacCallumore. It was so, and Reuben gave her the papers to prove it, and a letter to the Duke of Argyle; and she, begging him to do what he could for her father and sister, left the room hastily. With a strong heart, and a frame patient of fatigue, Jeannie Deans, travelling at the rate of twenty miles and more a day, traversed the southern part of Scotland, where her bare feet attracted no attention. She had to conform to the national extravagance in England, and confessed afterwards "that besides the wastrife, it was lang or she could walk as comfortably with the shoes as without them"; but found the people very hospitable on the whole, and sometimes got a cast in a waggon. At last London was reached, and an audience obtained with the Duke of Argyie. His Grace's heart warmed to the tartan when Jeannie appeared before him in the dress of a Scottish maiden of her class. His grandfather's letter, too, was a strong injunction to assist Stephen Butler, his friends or family, and he exerted himself to such good purpose, that he brought her into the presence of the queen to plead her cause for herself. Her majesty smiled at Jeannie's awestruck manner and broad Northern accent, and listened kindly, but said: "If the king were to pardon your sister, it would in all probability do her little good, for I suppose the people of Edinburgh would hang her out of spite." But Jeannie said: "She was confident that baith town and country would rejoice to see his majesty taking compassion on a poor unfriended creature." The queen was not convinced of the propriety of showing any marked favour to Edinburgh so soon - "the whole nation must be in a league to screen the murderers of Porteous" - but Jeannie pleaded her sister's cause with a pathos at once simple and solemn, and her majesty ended by giving her a housewife case to remind her of her interview with Queen Caroline, and promised her warm intercession with the king. The Duke of Argyie came to Jeannie's cousin's, where she was staying, in a few days to say that a pardon had been dispatched to Effie Deans, on condition of her banishing herself forth of Scotland for fourteen years - a qualification which greatly grieved the affectionate disposition of her sister. IV. - In After Years When Jeannie set out from London on her homeward journey, it was not to travel on foot, but in the Duke of Argyle's carriage, and the end of the journey was not Edinburgh, but the isle of Roseneath, in the Firth of Clyde. When the landing-place was reached, it was in the arms of her father that Jeannie was received. It was too wonderful to be believed - but the form was indisputable. Douce David Deans himself, in his best light-blue Sunday coat, with broad metal buttons, and waistcoat and breeches of the same. "Jeannie - my ain Jeannie - my best - my maist dutiful bairn! The Lord of Israel be thy father, for I am hardly worthy of thee! Thou hast redeemed our captivity, brought back the honour of our house!" These words broke from him not without tears, though David was of no melting mood. "And Effie - and Effie, dear father?" was Jeannie's eager question. "You will never see her mair, my bairn," answered Deans, in solemn tones. "She is dead! It has come ower late!" exclaimed Jeannie, wringing her hands. "No, Jeannie, she lives in the flesh, and is at freedom from earthly restraint. But she has left her auld father, that has wept and prayed for her. She has left her sister, that travailed and toiled for her like a mother. She has made a moonlight flitting of it." "And wi' that man - that fearfu' man?" said Jeannie. "It is ower truly spoken," said Deans. "But never, Jeannie never more let her name be spoken between you and me." The next surprise for Jeannie Deans was the appearance of Reuben Butler, who had been appointed by the Duke of Argyle to the kirk of Knocktarlitie, at Roseneath; and within a reasonable time after the new minister had been comfortably settled in his living, the banns were called, and long wooing of Reuben and Jeannie was ended by their union in the holy bands of matrimony. Effie, married to Robertson, whose real name was Staunton, paid a furtive visit to her sister, and many years later, when her husband was no longer a desperate outlaw, but Sir George Staunton, and beyond anxiety of recognition, the two sisters corresponded freely, and Lady Staunton even came to stay with Mrs. Butler, after old Deans was dead. A famous woman in society was Lady Staunton, but she was childless, for the child of her shame, carried off by gypsies, she saw no more. Jeannie and Reuben, happy in each other, in the prosperity of their family, and the love and honour of all by gypsies, she saw no more. |