|

|

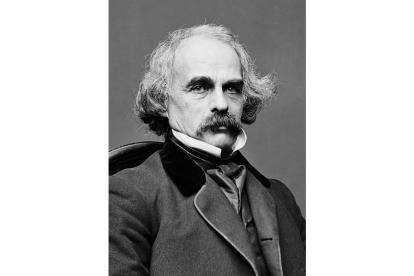

by Nathaniel Hawthorne The original, squashed down to read in about 20 minutes  (1851) Nathaniel Hathorne (July 4, 1804 - May 19, 1864) was a diplomat and story teller from Salem, Massachusetts, a descendant of John Hathorne a judge in the notorious Salem witch trials. Nathaniel altered his name to "Hawthorne" in order to hide this relation. He worked at a Custom House and joined Brook Farm, a transcendentalist community, before a political appointment took Hawthorne and family to Europe. Abridged: JH For more works by Nathaniel Hawthorn, see The Index Half-way down a by-street of one of our New England towns stands a rusty wooden house, with seven acutely-peaked gables, and a huge clustered chimney in the midst. The street is Pyncheon Street; the house is the old Pyncheon House; and an elm tree before the door is known as the Pyncheon elm. Pyncheon Street formerly bore the humbler appellation of Maule's Lane, from the name of the original occupant of the soil, before whose cottage door it was a cow-path. In the growth of the town, however, after some thirty or forty years, the site covered by the rude hovel of Matthew Maule (originally remote from the centre of the earlier village) had become exceedingly desirable in the eyes of a prominent personage, who asserted claims to the land on the strength of a grant from the Legislature. Colonel Pyncheon, the claimant, was a man of iron energy of purpose. Matthew Maule, though an obscure man, was stubborn in the defense of what he considered his right. The dispute remained for years undecided, and came to a close only with the death of old Matthew Maule, who was executed for the crime of witchcraft. It was remembered afterwards how loudly Colonel Pyncheon had joined in the general cry to purge the land from witchcraft, and had sought zealously the condemnation of Matthew Maule. At the moment of execution - with the halter about his neck, and while Colonel Pyncheon sat on horseback grimly gazing at the scene - Maule had addressed him from the scaffold, and uttered a prophecy. "God," said the dying man, pointing his finger at the countenance of his enemy, "God will give him blood to drink!" When it was understood that Colonel Pyncheon intended to erect a spacious family mansion on the spot first covered by the log-built hut of Matthew Maule the village gossips shook their heads, and hinted that he was about to build his house over an unquiet grave. But the Puritan soldier and magistrate was not a man to be turned aside from his scheme by dread of the reputed wizzard's ghost. He dug his cellar, and laid deep the foundations of his mansion; and the head-carpenter of the House of the Seven Gables was no other than Thomas Maule, the son of the dead man from whom the right to the soil had been wrested. On the day the house was finished Colonel Pyncheon bade all the town to be his guests, and Maude's Lane - or Pyncheon Street, as it was now called - was thronged at the appointed hour as with a congregation on its way to church. But the founder of the stately mansion did not stand in his own hall to welcome the eminent persons who presented themselves in honour of the solemn festival, and the principal domestic had to explain that his master still remained in his study, which he had entered an hour before. The lieutenant-governor took the matter into his hands, and knocked boldly at the door of the colonel's private apartment, and, getting no answer, he tried the door, which yielded to his hand, and was flung wide open by a sudden gust of wind. The company thronged to the now open door, pressing the lieutenant-governor into the room before them. A large map and a portrait of Colonel Pyncheon were conspicuous on the walls, and beneath the portrait sat the colonel himself in an elbow chair, with a pen in his hand. A little boy, the colonel's grandchild, now made his way among the guests, and ran towards the seated figure; then, pausing halfway, he began to shriek with terror. The company drew nearer, and perceived that there was blood on the colonel's cuff and on his beard, and an unnatural distortion in his fixed stare. It was too late to render assistance. The iron-hearted Puritan, the relentless persecutor, the grasping and strong-willed man, was dead! Dead in his new house! Colonel Pyncheon's sudden and mysterious end made a vast deal of noise in its day. There were many rumours, and a great dispute of doctors over the dead body. But the coroner's jury sat upon the corpse, and, like sensible men, returned an unassailable verdict of "Sudden Death." The son and heir came into immediate enjoyment of a considerable estate, but a claim to a large tract of country in Waldo County, Maine, which the colonel, had he lived, would undoubtedly have made good, was lost by his decease. Some connecting link had slipped out of the evidence, and could not be found. Still, from generation to generation, the Pyncheons cherished an absurd delusion of family importance on the strength of this impalpable claim; and from father to son they clung with tenacity to the ancestral house for the better part of two centuries. The most noted event in the Pyncheon annals in the last fifty years had been the violent death of the chief member of the family - an old and wealthy bachelor. One of his nephews, Clifford, was found guilty of the murder, and was sentenced to perpetual imprisonment. This had happened thirty years ago, and there were now rumours that the long-buried criminal was about to be released. Another nephew had become the heir, and was now a judge in an inferior court. The only members of the family known to be extant, besides the judge and the thirty years' prisoner, were a sister of the latter, wretchedly poor, who lived in the House of the Seven Gables by the will of the old bachelor, and the judge's single surviving son, now travelling in Europe. The last and youngest Pyncheon was a little country girl of seventeen, whose father - another of the judge's cousins - was dead, and whose mother had taken another husband. Miss Hepzibah Pyncheon was reduced to the business of setting up a pretty shop, and that in the Pyncheon house where she had spent all her days. After sixty years of idleness and seclusion, she must earn her bread or starve, and to keep shop was the only resource open to her. The first customer to cross the threshold was a young man to whom old Hepzibah let certain remote rooms in the House of the Seven Gables. He explained that he had looked in to offer his best wishes, and to see if he could give any assistance. Poor Hepzibah, when she heard the kindly tone of his voice, began to sob. "Ah, Mr. Holgrave," she cried, "I never can go through with it! Never, never, never! I wish I were dead in the old family tomb with all my forefathers - yes, and with my brother, who had far better find me there than here! I am too old, too feeble, and too hopeless! If old Maule's ghost, or a descendant of his, could see me behind the counter to-day, he would call it the fulfilment of his worst wishes. But I thank you for your kindness, Mr. Holgrave, and will do my utmost to be a good shopkeeper." On Holgrave asking for half a dozen biscuits, Hepzibah put them into his hand, but rejected the compensation. "Let me be a lady a moment longer," she said, with a manner of antique stateliness. "A Pyncheon must not - at all events, under her forefathers' roof - receive money for a morsel of bread from her only friend." As the day went on the poor lady blundered hopelessly with her customers, and committed the most unheard-of errors, so that the whole proceeds of her painful traffic amounted, at the close, to half a dozen coppers. That night the little country cousin, Phoebe Pyncheon, arrived at the gloomy old house. Hepzibah knew that circumstances made it desirable for the girl to establish herself in another home, but she was reluctant to bid her stay. "Phoebe," she said, on the following morning, "this house of mine is but a melancholy place for a young person to be in. It lets in the wind and rain, and the snow, too, in the winter time; but it never lets in the sunshine! And as for myself, you see what I am - a dismal and lonesome old woman, whose temper is none of the best, and whose spirits are as bad as can be. I cannot make your life pleasant, Cousin Phoebe; neither can I so much as give you bread to eat." "You will find me a cheerful little body," answered Phoebe, smiling, "and I mean to earn my bread. You know I have not been brought up a Pyncheon. A girl learns many things in a New England village." "Ah, Phoebe," said Hepzibah, sighing, "it is a wretched thought that you should fling away your young days in a place like this. And, after all, it is not even for me to say who shall be a guest or inhabitant of the old Pyncheon house. Its master is coming." "Do you mean Judge Pyncheon?" asked Phoebe, in surprise. "Judge Pyncheon!" answered her cousin angrily. "He will hardly cross the threshold while I live. You shall see the face of him I speak of." She went in quest of a miniature, and returned and placed it in Phoebe's hand. "How do you like the face?" asked Hepzibah. "It is handsome; it is very beautiful!" said Phoebe admiringly. "It is as sweet a face as a man's can be or ought to be. Who is it, Cousin Hepzibah?" "Did you never hear of Clifford Pyncheon?" "Never. I thought there were no Pyncheons left, except yourself and our Cousin Jaffrey, the judge. And yet I seem to have heard the name of Clifford Pyncheon. Yes, from my father, or my mother. But hasn't he been dead a long while?" "Well, well, child, perhaps he has," said Hepzibah, with a sad, hollow laugh; "but in old houses like this, you know, dead people are very apt to come back again. And, Cousin Phoebe, if your courage does not fail you, we will not part soon. You are welcome to such a home as I can offer you." The day after Phoebe's arrival there was a constant tremor in Hepzibah's frame. With all her affection for a young cousin there was a recurring irritability. "Bear with me, my dear child!" she cried; "bear with me, for I love you, Phoebe; and truly my heart is full to the brim! By-and-by I shall be kind, and only kind." "What has happened?" asked Phoebe. "What is it that moves you so?" "Hush! He is coming!" whispered Hepzibah. "Let him see you first, Phoebe; for you are young and rosy, and cannot help letting a smile break out. He always liked bright faces. And mine is old now, and the tears are hardly dry on it. Draw the curtain a little, but let there be a good deal of sunshine, too. He has had but little sunshine in his life, poor Clifford; and, oh, what a black shadow! Poor - poor Clifford!" There was a step in the passage-way, above stairs. It seemed to Phoebe the same that she had heard in the night, as in a dream. Very slowly the steps came downstairs, and paused for a long time at the door. Hepzibah, unable to endure the suspense, rushed forward, threw open the door, and led in the stranger by the hand. At the first glance Phoebe saw an elderly man, in an old-fashioned dressing gown, with grey hair, almost white, of an unusual length. The expression of his countenance seemed to waver, glimmer, and nearly to die away, and feebly to recover itself again. "Dear Clifford," said Hepzibah, "this is our Cousin Phoebe, Arthur's only child, you know. She has come from the country to stay with us a while, for our old house has grown to be very lonely now." "Phoebe? Arthur's child?" repeated the guest. "Ah, I forget! No matter. She is very welcome." He seated himself in the place assigned him, and looked strangely around. His eyes met Hepzibah's, and he seemed bewildered and disgusted. "Is this you, Hepzibah?" he murmured sadly. "How changed! how changed!" "There is nothing but love here, Clifford," Hepzibah said softly - "nothing but love. You are at home." The guest responded to her tone by a smile, which but half lit up his face. It was followed by a coarser expression, and he ate his food with fierce voracity and asked for "more - more!" That day Phoebe attended to the shop, and the second person to enter it was a gentleman of portly figure and high respectability. "I was not aware that Miss Hepzibah Pyncheon had commenced business under such favourable auspices," he said, in a deep voice, "You are her assistant, I suppose?" "I certainly am," answered Phoebe. "I am a cousin of Miss Hepzibah, on a visit to her." "Her cousin, and from the country?" said the gentleman, bowing and smiling. "In that case we must be better acquainted, for you are my own little kinswoman likewise. Let me see, you must be Phoebe, the only child of my dear Cousin Arthur. I am your kinsman, my dear. Surely you must have heard of Judge Pyncheon?" Phoebe curtsied, and the judge bent forward to bestow a kiss on his young relative. But Phoebe drew back; there was something repulsive to her in the judge's demonstration, and on raising her eyes she was startled by the change in Judge Pyncheon's face. It had become cold, hard, and immitigable. "Dear me! What is to be done now?" thought the country girl to herself. "He looks as if there were nothing softer in him than a rock, nor milder than the east wind." Then all at once it struck Phoebe that this very Judge Pyncheon was the original of a miniature which Mr. Holgrave - who took portraits, and whose acquaintance she had made within a few hours of her arrival - had shown her yesterday. There was the same hard, stern, relentless look on the face. In reality, the miniature was copied from an old portrait of Colonel Pyncheon which hung within the house. Was it that the expression had been transmitted down as a precious heirloom, from that Puritan ancestor, in whose picture both the expression, and, to a singular degree, the features, of the modern judge were shown as by a kind of prophecy? But as it happened, scarcely had Phoebe's eyes rested again on the judge's countenance than all its ugly sternness vanished, and she found herself almost overpowered by the warm benevolence of his look. But the fantasy would not quit her that the original Puritan, of whom she had heard so many sombre traditions, had now stepped into the shop. "You seem to be a little nervous this morning," said the judge. "Has anything happened to disturb you - anything remarkable in Cousin Hepzibah's family - an arrival, eh? I thought so! To be an inmate with such a guest may well startle an innocent young girl!" "You quite puzzle me, sir!" replied Phoebe. "There is no frightful guest in the house, but only a poor, gentle, child-like man, whom I believe to be Cousin Hepzibah's brother. I am afraid that he is not quite in his sound senses; but so mild he seems to be that a mother might trust her baby with him. He startle me? Oh, no, indeed!" "I rejoice to hear so favourable and so ingenious an account of my Cousin Clifford," said the benevolent judge. "It is possible that you have never heard of Clifford Pyncheon, and know nothing of his history. But is Clifford in the parlour? I will just step in and see him. There is no need to announce me. I know the house, and know my Cousin Hepzibah, and her brother Clifford likewise. Ah, there is Hepzibah herself!" Such was the case. The vibrations of the judge's voice had reached the old gentlewoman in the parlour, where Clifford sat slumbering in his chair. "He cannot see you," said Hepzibah, with quivering voice. "He cannot see visitors." "A visitor - do you call me so?" cried the judge. "Then let me be Clifford's host, and your own likewise. Come at once to my house. I have often invited you before. Come, and we will labour together to make Clifford happy." "Clifford has a home here," she answered. "Woman," broke out the judge, "what is the meaning of all this? Have you other resources? Take care, Hepzibah, take care! Clifford is on the brink of as black a ruin as ever befel him yet!" From within the parlour sounded a tremulous, wailing voice, indicating helpless alarm. "Hepzibah!" cried the voice. "Entreat him not to come in. Go down on your knees to him. Oh, let him have mercy on me! Mercy!" The judge withdrew, and Hepzibah, deathly white, staggered towards Phoebe. "That man has been the horror of my life," she murmured. "Shall I never have courage enough to tell him what he is?" The shop thrived under Phoebe's management, and the acquaintance with Mr. Holgrave ripened into friendship. Then, after some weeks, Phoebe went away on a temporary visit to her mother, and the old house, which had been brightened by her presence, was once more dark and gloomy. It was during this absence of Phoebe's that Judge Pyncheon once more called and demanded to see Clifford. "You cannot see him," answered Hepzibah. "Clifford has kept his bed since yesterday." "What! Clifford ill!" said the judge, starting. "Then I must, and will see him!" The judge explained the reason for his urgency. He believed that Clifford could give the clue to the dead uncle's wealth, of which not more than a half had been mentioned in his will. If Clifford refused to reveal where the missing documents were placed, the judge declared he would have him confined in a public asylum as a lunatic, for there were many witnesses of Clifford's simple childlike ways. "You are stronger than I," said Hepzibah, "and you have no pity in your strength. Clifford is not now insane; but the interview which you insist upon may go far to make him so. Nevertheless, I will call Clifford!" Hepzibah went in search of her brother, and Judge Pyncheon flung himself down in an old chair in the parlour. He took his watch from his pocket and held it in his hand. But Clifford was not in his room, nor could Hepzibah find him. She returned to the parlour, calling out to the judge as she came, to rise and help find Clifford. But the judge never moved, and Clifford appeared at the door, pointing his finger at the judge, and laughing with strange excitement. "Hepzibah," he said, "we can dance now! We can sing, laugh, play, do what we will! The weight is gone, Hepzibah - gone off this weary old world, and we may be as lighthearted as little Phoebe herself! What an absurd figure the old fellow cuts now, just when he fancied he had me completely under his thumb!" Then the brother and sister departed hastily from the house, and left Judge Pyncheon sitting in the old house of his forefathers. Phoebe and Holgrave were in the house together when the brother and sister returned, and Holgrave had told her of the judge's sudden death. Then, in that hour so full of doubt and awe, the one miracle was wrought, without which every human existence is a blank, and the bliss which makes all things true, beautiful, and holy shone around this youth and maiden. They were conscious of nothing sad or old. Presently the voices of Clifford and Hepzibah were heard at the door, and when they entered Clifford appeared the stronger of the two. "It is our own little Phoebe! Ah! And Holgrave with her!" he exclaimed. "I thought of you both as we came down the street. And so the flower of Eden has bloomed even in this old, darksome house to-day." A week after the judge's death news came of the death of his son, and so Hepzibah became rich, and so did Clifford, and so did Phoebe, and, through her, Holgrave. It was far too late for the formal vindication of Clifford's character to be worth the trouble and anguish involved. For the truth was that the uncle had died by a sudden stroke, and the judge, knowing this, had let suspicion and condemnation fall on Clifford, only because he had himself been busy among the dead man's papers, destroying a later will made out in Clifford's favour, and because it was found the papers had been disturbed, to avert suspicion from the real offender he had let the blame fall on his cousin. Clifford was content with the love of his sister and Phoebe and Holgrave. The good opinion of society was not worth publicly reclaiming. It was Holgrave who discovered the missing document the judge had set his heart on obtaining. "And now, my dearest Phoebe," said Holgrave, "how will it please you to assume the name of Maule? In this long drama of wrong and retribution I represent the old wizzard, and am probably as much of a wizzard as ever my ancestor was." Then, with Hepzibah and Clifford, Phoebe and Holgrave left the old house for ever. |