|

|

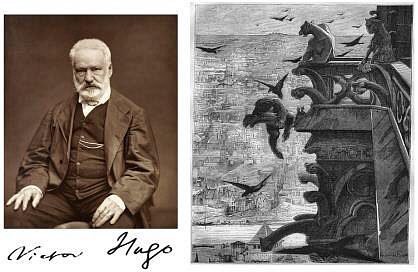

(Notre Dame de Paris) by Victor Hugo The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (Paris, 1831) Victor Marie Hugo was born on 26th February 1802 at the ancient city of Besançon in Eastern France. His political views were firm and radical, though somewhat variable. Hugo was elevated to the peerage by King Louis-Philippe, but his opposition to Louis Napoleon's seizing power in 1851 led to his exile in Jersey, from where he was, in turn, expelled for criticising Queen Victoria. He finally settled in Guernsey, returning to France in 1870 as a significant national hero. Abridged: JH/GH For more books by Victor Hugo, see The Index I. - The Hunchback of Notre Dame It was January 6, 1482, and all Paris was keeping the double festival of Epiphany and the Feast of Fools. The Lord of Misrule was to be elected, and all who were competing for the post came in turn and made a grimace at a broken window in the great hall of the Palace of Justice. The ugliest face was to be acclaimed victor by the populace, and shouts of laughter greeted the grotesque appearances. The vote was unanimous in favour of the hunchback of Notre Dame. He had but stood at the window, and at once had been elected. The square nose, the horseshoe shaped mouth, the one eye, overhung by a bushy red eyebrow, the forked chin, and the strange expression of amazement, malice, and melancholy - who had seen such a grimace? It was only when the crowd had carried away the Lord of Misrule in triumph that they understood that the grimace was the hunchback's natural face. In fact, the entire man was a grimace. Humpbacked, an enormous head, with bristles of red hair; broad feet, huge hands, crooked legs; and, with all this deformity, a wonderful vigour, agility, and courage. Such was the newly chosen Lord of Misrule - a giant broken to pieces and badly mended. He was recognised by the crowd in the streets, and shouts went up. "It is Quasimodo, the bell-ringer! Quasimodo, the hunchback of Notre Dame!" A pasteboard tiara and imitation robes were placed on him, and Quasimodo submitted with a sort of proud docility. Then he was seated upon a painted barrow, and twelve men raised it to their shoulders; and the procession, which included all the vagrants and rascals of Paris, set out to parade the city. There was a certain rapture in this journey for Quasimodo. For the first time in his life he felt a thrill of vanity. Hitherto humiliation and contempt had been his portion; and now, though he was deaf, he could enjoy the plaudits of the mob - mob which he hated because he felt that it hated him. Suddenly, as Quasimodo passed triumphantly along the streets, the spectators saw a man, dressed like a priest, dart out and snatch away the gilded crosier from the mock pope. A cry of terror rose. The terrible Quasimodo threw himself from his barrow, and everyone expected to see him tear the priest limb from limb. Instead, he fell on his knees before the priest, and submitted to have his tiara torn from him and his crosier broken. The fraternity of fools determined to defend their pope so abruptly dethroned; but Quasimodo placed himself in front of the priest, put his fists up, and glared at his assailants, so that the crowd melted before him. Then, at the grave beckoning of the priest, Quasimodo followed, and the two disappeared down a narrow side street. The one human being whom Quasimodo loved was this priest, Claude Frollo, Archbishop of Paris. And this was quite natural. For it was Claude Frollo who had found the hunchback - a deserted, forsaken child left in a sack at the entrance to Notre Dame, and, in spite of his deformities, had taken him, fed him, adopted him, and brought him up. Claude Frollo taught him to speak, to read, and to write, and had made him bell-ringer at Notre Dame. Quasimodo grew up in Notre Dame. Cut off from the world by his deformities, the church became his universe, and his gratitude was boundless when he was made bell-ringer. The bells had made him deaf, but he could understand by signs Claude Frollo's wishes, and so the archdeacon became the only human being with whom Quasimodo could hold any communication. Notre Dame and Claude Frollo were the only two things in the world for Quasimodo, and to both he was the most faithful watchman and servant. In the year 1482 Quasimodo was about twenty, and Claude Frollo thirty-six. The former had grown up, the latter had grown old. II. - Esmeralda On that same January 6, 1482, a young girl was dancing in an open space near a great bonfire in Paris. She was not tall but seemed to be, so erect was her figure. She danced and twirled upon an old piece of Persian carpet, and every eye in the crowd was riveted upon her. In her grace and beauty this gypsy girl seemed more than mortal. One man in the crowd stood more absorbed than the rest in watching the dancer. It was Claude Frollo, the archdeacon: and though his hair was grey and scanty, in his deep-set eyes the fire and spirit of youth still sparkled. When the young girl stopped at last, breathless, the people applauded eagerly. "Djali," said the gypsy, "it's your turn now." And a pretty little white goat got up from a corner of the carpet. "Djali, what month in the year is this?" The goat raised his forefoot and struck once upon the tambourine held out to him. The crowd applauded. "Djali, what day of the month is it?" The goat struck the tambourine six times. The people thought it was wonderful. "There is sorcery in this!" said a forbidding voice in the crowd. It was the voice of the priest Claude Frolic. Then the gypsy began to take up a collection in her tambourine, and presently the crowd dispersed. Later in the day, when darkness had fallen, as the gypsy and her goat were proceeding to their lodgings, Quasimodo seized hold of the girl and ran off with her. "Murder! Murder!" shrieked the unfortunate gypsy. "Halt! Let the girl go, you ruffian!" exclaimed, in a voice of thunder, a horseman who appeared suddenly from a cross street. It was a captain of the King's Archers, armed from head to foot, and sword in hand. He tore the gypsy girl from the arms of the astonished Quasimodo, and placed her across his saddle. Before the hunchback could recover from his surprise, a squadron of royal troops, going on duty as extra watchmen, surrounded him, and he was seized and bound. The gypsy girl sat gracefully upon the officer's saddle, placing both hands upon the young man's shoulders, and gazing at him fixedly. Then breaking the silence, she said tenderly, "What is your name, M. l'Officier?" "Captain Phaebus de Châteaupers, at your service, my pretty maid!" said the officer, drawing himself up. "Thank you." And while Captain Phaebus twirled his mustache, she slipped from his horse and vanished like a flash of lightning. "The bird has flown, but the bat remains, captain," said one of the troopers, tightening Quasimodo's bonds. Quasimodo being deaf, understood nothing of the proceedings in the court next day, when he was charged with creating a disturbance, and of rebellion and disloyalty to the King's Archers. The chief magistrate, also being deaf and at the same time anxious to conceal his infirmity, understood nothing that Quasimodo said. The hunchback was sentenced to be taken to the pillory in the Grève, to be beaten, and to be kept there for two hours. Quasimodo remained utterly impassive, while the crowd which yesterday had hailed him as Lord of Misrule now greeted him with hooting and derision. The pillory was a simple cube of masonry, some ten feet high, and hollow within. A horizontal wheel of oak was at the top, and to this the victim was bound in a kneeling posture. A very steep flight of stone steps led to the wheel. All the people laughed merrily when Quasimodo was seen in the pillory; and when he had been beaten by the public executioner, they added to the wretched sufferer's misery by insults, and, occasionally, stones. There was hardly a spectator in the crowd that had not some grudge, real or imagined, against the hunchback bell-ringer of Notre Dame. Quasimodo had endured the torturer's whip with patience, but he rebelled against the stones, and struggled in his fetters till the old pillory-wheel creaked on its timbers. Then, as he could accomplish nothing by his struggles, his face became quiet again. For a moment the cloud was lightened when the poor victim saw a priest seated on a mule approach in the roadway. A strange smile came on the face of Quasimodo as he glanced at the priest; yet when the mule was near enough to the pillory for his rider to recognise the prisoner, the priest cast down his eyes, turned back hastily, as if in a hurry to avoid humiliating appeals, and not at all anxious to be greeted by a poor wretch in the pillory. The priest was the archdeacon, Claude Frollo. The smile on Quasimodo's face became bitter and profoundly sad. Time passed. He had been there at least an hour and a half, wounded, incessantly mocked, and almost stoned to death. Suddenly he again struggled in his chains with renewed despair, and breaking the silence which he had kept so stubbornly, he cried in a hoarse and furious voice, "Water!" The exclamation of distress, far from exciting compassion, only increased the amusement of the Paris mob. Not a voice was raised, except to mock at his thirst. Quasimodo cast a despairing look upon the crowd, and repeated in a heartrending voice, "Water!" Everyone laughed. A woman aimed a stone at his head, saying, "That will teach you to wake us at night with your cursed chimes!" "Here's a cup to drink out of!" said a man, throwing a broken jug at his breast. "Water!" repeated Quasimodo for the third time. At this moment he saw the gypsy girl and her goat come through the crowd. His eye gleamed. He did not doubt that she, too, came to be avenged, and to take her turn at him with the rest. He watched her nimbly climb the ladder. Rage and spite choked him. He longed to destroy the pillory; and had the lightning of his eye had power to blast, the gypsy girl would have been reduced to ashes long before she reached the platform. Without a word she approached the sufferer, loosened a gourd from her girdle, and raised it gently to the parched lips of the miserable man. Then from his eye a great tear trickled, and rolled slowly down the misshapen face, so long convulsed with despair. The gypsy girl smilingly pressed the neck of the gourd to Quasimodo's jagged mouth. He drank long draughts; his thirst was feverish. When he had done, the poor wretch put out his black lips to kiss the hand which had helped him. But the girl, remembering the violent attempt of the previous night, and not quite free from distrust, withdrew her hand quickly. Quasimodo fixed upon her a look of reproach and unspeakable sorrow. The sight of this beautiful girl succouring a man in the pillory so deformed and wretched seemed sublime, and the people were immediately affected by it. They clapped their hands, and shouted, "Noël! Noël!" Esmeralda - for that was the name of the gypsy girl - came down from the pillory, and a mad woman called out, "Come down! Come down! You will go up again!" Presently Quasimodo was released, and the mob thereupon dispersed. III. - The Archdeacon's Passion In spite of the austerity of Claude Frollo's life, pious people suspected him of magic. His silence and secretiveness encouraged this feeling. He was known to be at work in the long hours of the night in his cell in Notre Dame, and he wandered about the streets like a spectre. Whenever the gypsy girl placed her carpet within sight of Claude Frollo's cell and began to dance the priest turned from his books and, resting his head in his hands, gazed at her. Then he would go down into the public thoroughfares, lured on by some burning passion within. Quasimodo, too, would desist from his bell-ringing to look at the dancing girl. The hotter the fire of passion burned within the priest the farther Esmeralda moved from him. He discovered that she was in love with Captain Phoebus, her rescuer, and this knowledge added fuel to the flames. One purpose now was clear to him. He would give up all for the dancing girl, and she should be his. But if Esmeralda refused to come to him, then the archdeacon resolved that she should die before she married anyone else. At any time he could have her arrested on the charge of sorcery, and the goat's tricks would easily procure a conviction. Captain Phoebus, having invited Esmeralda to meet him at a wineshop, the priest followed the couple, and when the captain, to whom the girl was the merest diversion, began to make love, Claude Frollo, unable to contain himself, rushed in unobserved and stabbed him. Captain Phoebus was taken up for dead, and the priest vanished as silently as he had come. The soldiers of the watch found Esmeralda, and said, "This is the sorceress who has stabbed our captain." So Esmeralda was brought to trial on the charge of witchcraft, and every day the priest from Notre Dame came into court. It was a tedious process, for not only was the girl on trial, but the goat also, in accordance with the custom of the times, was under arrest. All that Esmeralda wanted to know was whether Phoebus was still alive, and she was told by the judges he was dying. The indictment against her was "that with her accomplice, the bewitched goat, she did murder and stab, in league with the powers of darkness, by the aid of charms and spells, a captain of the king's troops, one Phoebus de Châteaupers." And it was vain that the girl denied vehemently her guilt. "How do you explain the charge brought against you?" said the president. "I have told you already I do not know," said Esmeralda, in a broken voice. "It was a priest - a priest who is always pursuing me" "That's it," said the president; "it is a goblin monk." The goat having performed his simple tricks in the presence of the court, and Esmeralda still refusing to admit her guilt, the president ordered her to be put to the question. She was placed on the rack, and at the first turn of the screw promised to confess everything. Then the lawyers put a number of questions to her, and Esmeralda answered "Yes" in every case. It was plain that her spirit was utterly broken. Then the court having read the confession, sentence was pronounced. She was to be taken to the Grève, where the pillory stood, and, in atonement for the crimes confessed, there hanged and strangled on the city gibbet, "and likewise this your goat." "It must be a dream," the girl murmured, when she heard the sentence. But, if Esmeralda had yielded at the first turn of the rack, nothing would make her yield to Claude Frollo when he came to see her in prison. In vain he promised her life and liberty if she would only agree to love him. In vain he reproached her with having brought disturbance and disquiet into his soul. All that Esmeralda could say was, "Have pity on me! - have pity on me!" But she would not give up Phoebus. And when the priest declared Phoebus was dead, she turned upon him and called him "monster and assassin!" Claude Frollo, unable to move her, decided to let her die, and the day of execution arrived. As for Captain Phoebus, he recovered; but, as he was about to be engaged to a young lady of wealth, he thought it better to say nothing about the gypsy girl. But Esmeralda was not hanged that day. Just as the hangman's assistants were about to do their work, Quasimodo, who had been watching everything from his gallery in Notre Dame, slid down by a rope to the ground, rushed at the two executioners, flung them to the earth with his huge fists, seized the gypsy girl, as a child might a doll, and with one bound was in the church, holding her above his head, and shouting in a tremendous voice, "Sanctuary!" "Sanctuary! Sanctuary!" The mob took up the cry, and ten thousand hands clapped approval. The hangman stood stupefied. Within the precincts of Notre Dame the prisoner was secure; the cathedral was a sure refuge, all human justice ended at its threshold. IV. - The Attack on Notre Dame Quasimodo did not stop running and shouting "Sanctuary!" till he reached a cell built over the aisles in Notre Dame. Here he deposited Esmeralda carefully, untied the ropes which bruised her arms, and spread a mattress on the floor; then he left her, and returned with a basket of provisions. The girl lifted her eyes to thank him, but could not utter a word, so frightful was he to look at. Quasimodo only said, "I frighten you because I am ugly. Do not look at me, then, but listen. All day you must stay here, at night you can walk anywhere about the church. But, day or night, do not leave the church, or you will be lost. They would kill you, and I should die." Then he vanished, but when she awoke next morning she saw him at the window of her cell. "Don't be frightened," he said. "I am your friend. I only came to see if you were asleep. I am deaf, you did not know that? I never realised how ugly I was till now. I seem to you like some awful beast, eh? And you - you are a sunbeam!" As the days went by calm returned to Esmeralda's soul, and with calm had come the sense of security, and with security hope. Two forces were now at work to remove her from Notre Dame. The archdeacon, leaving Paris to avoid her execution, had returned - to learn where Esmeralda was situated. From his cell in Notre Dame he observed her movements, and, in his madness, jealous of Quasimodo's service to her, resolved to have her removed. If she still refused him he would give her up to justice. Esmeralda's friends, all the gypsies, vagrants, cutthroats, and pick-pockets of Paris, to the number of six thousand, also resolved that they would forcibly rescue her from Notre Dame, lest some evil should overtake her. Paris at that time had neither police nor adequate city watchmen. At midnight the monstrous army of vagrants set out, and it was not until they were outside the church that they lit their torches. Quasimodo, every night on the watch, at once supposed that the invaders had some foul purpose against Esmeralda, and determined to defend the church at all cost. The battle raged furiously at the great west doors. Hammers, pincers, and crow-bars were at work outside. Quasimodo retaliated by heaving first a great beam of wood, and then stones and other missiles on the besiegers. Finally, when they had reared a tall ladder to the first gallery, and had crowded it with men, Quasimodo, by sheer force, pushed the ladder away, and it tottered and fell right back. The battle only ended on the arrival of a large company of King's Archers, when the vagrants, defeated by Quasimodo, retired fighting. While the battle raged Claude Frollo, with the aid of a disreputable young student of his acquaintance, persuaded Esmeralda to leave the church by a secret door at the back, and to escape by the river. The priest was so hidden in his cloak that the girl did not recognise him till they were alone in the city. In the Grève, at the foot of the public scaffold where the gallows stood, Claude Frollo made his last appeal. "Listen!" he said. "I have saved you, and I can save you altogether, if you choose. Choose between me and the gibbet!" There was silence, and then Esmeralda said, "It is less horrible to me than you are." He poured out his soul passionately, telling her that his life was nothing without her love, but the girl never moved. It was daylight now. "For the last time, will you be mine?" She answered emphatically, "No!" Then he called out as loud as he could, and presently a body of armed men appeared. Soon the public hangman was aroused, and the execution which had been interrupted by Quasimodo's heroic rescue was carried out. Meantime, what of Quasimodo? He had rushed to her cell when the king's troops, having beaten off the vagrants, entered the church, and it was empty! Then he had explored every nook and cranny of Notre Dame, and again and again gone the round of the church. For an hour he sat in despair, his body convulsed by sobs. Suddenly he remembered that Claude Frollo had a secret key, and decided that the priest must have carried her off. At that very moment Claude returned to Notre Dame, after handing over Esmeralda to the hangman. Quasimodo watched him ascend to the balustrade at the top of the tower, and then followed him; the priest's attention was too absorbed to hear the hunchback's step. Claude rested his arms on the balustrade, and gazed intently at the gallows in the Grève. Quasimodo tried to make out what it was the priest stared at, and then he recognised Esmeralda in the hangman's arms on the ladder, and in another second the hangman had done his work. A demoniac laugh broke from the livid lips of Claude Frollo; Quasimodo could not hear this laughter, but he saw it. He rushed furiously upon the archdeacon, and with his great fists he hurled Claude Frollo into the abyss over which he leaned. The archdeacon caught at a gutter, and hung suspended for a few minutes, and then fell - more than two hundred feet. Quasimodo raised his eyes to the gypsy, whose body still swung from the gibbet; and then lowered them to the shapeless mass on the pavement beneath. "And these were all I have ever loved!" he said, sobbing. He was never seen again in Notre Dame. Some two years later, when there were certain clearances in the vault where the body of Esmeralda had been deposited, the skeleton of a man, deformed and twisted, was found in close embrace with the skeleton of a woman. A little silk bag which Esmeralda had always worn was around the neck of the skeleton of the woman. |