|

|

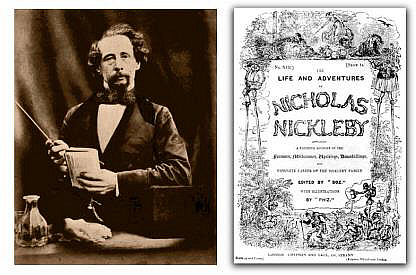

by Charles Dickens The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (London, 1839) Writing in 1848, Charles Dickens declared that when "Nicholas Nickleby" was begun in 1838 "there were then a good many-cheap Yorkshire schools in existence. There are very few now." For more works by Dickens, see The Index Abridged: GH/JH I. - A Yorkshire Schoolmaster Mr. Nickleby, a country gentleman of small estate, having endeavoured to increase his scanty fortune by speculation, found himself ruined; he took to his bed (apparently resolved to keep that, at all events), and, after embracing his wife and children, very soon departed this life. So Mrs. Nickleby went to London to wait upon her brother-in-law, Mr. Ralph Nickleby, and with her two children, Nicholas, then nineteen, and Kate, a year or two younger, took lodgings in the Strand. It was to these apartments that Ralph Nickleby, a hard, unscrupulous, cunning money-lender, came on receipt of the widow's note. "Are you willing to work, sir?" said Ralph, frowning at his nephew. "Of course I am," replied Nicholas haughtily. "Then see here," said his uncle. "This caught my eyes this morning, and you may thank your stars for it." With that Mr. Ralph Nickleby took a newspaper from his pocket and read the following advertisement. "Education. - At Mr. Wackford Squeers' Academy, Dotheboys Hall, at the delightful village of Dotheboys, in Yorkshire, youths are boarded, clothed, booked, furnished with pocket-money, instructed in all languages living or dead, mathematics, orthography, geometry, trigonometry, the use of the globes, algebra, single-stick (if required), writing, arithmetic, fortification, and every other branch of classic literature. Terms, twenty guineas per annum. No extras, no vacations, and diet unparalleled. Mr. Squeers is in town, and attends daily from one till four, at the Saracen's Head, Snow Hill. N.B. - An able assistant wanted. Annual salary, £5, A Master of Arts would be preferred." "There!" said Ralph, folding the paper again. "Let him get that situation and his fortune's made. If he don't like that, let him get one for himself." "I am ready to do anything you wish me," said Nicholas, starting gaily up. "Let us try our fortune with Mr. Squeers at once; he can but refuse." "He won't do that," said Ralph. "He will be glad to have you on my recommendation. Make yourself of use to him, and you'll rise to be a partner in the establishment in no time." Nicholas, having taken down the address of Mr. Wackford Squeers, the uncle and nephew at once went forth in quest of that accomplished gentleman. "Perhaps you recollect me?" said Ralph, looking narrowly at the schoolmaster, as the Saracen's Head. "You paid me a small account at each of my half-yearly visits to town for some years, I think, sir," replied Squeers, "for the parents of a boy who, unfortunately - - " "Unfortunately died at Dotheboys Hall," said Ralph, finishing the sentence. "And now let us come to business. You have advertised for an assistant. Do you really want one?" "Certainly," answered Squeers. "Here he is!" said Ralph. "My nephew Nicholas, hot from school, is just the man you want." "I am afraid," said Squeers, perplexed with such an application from a youth of Nicholas's figure - "I am afraid the young man won't suit me." "I fear, sir," said Nicholas, "that you object to my youth, and to not being a Master of Arts?" "The absence of the college degree is an objection." replied Squeers, considerably puzzled by the contrast between the simplicity of the nephew and the shrewdness of the uncle. "Let me have two words with you," said Ralph. The two words were had apart; in a couple of minutes Mr. Wackford Squeers' announced that Mr. Nicholas Nickleby was from that moment installed in the office of first assistant master at Dotheboys Hall. "At eight o'clock to-morrow morning, Mr. Nickleby," said Squeers, "the coach starts. You must be here at a quarter before, as we take some boys with us." "And your fare down I have paid," growled Ralph. "So you'll have nothing to do but keep yourself warm." II. - At Dotheboys Hall "Past seven, Nickleby," said Mr. Squeers on the first morning after the arrival at Dotheboys Hall. "Come, tumble up. Here's a pretty go, the pump's froze. You can't wash yourself this morning, so you must be content with giving yourself a dry polish till we break the ice in the well, and can get a bucketful out for the boys." Nicholas huddled on his clothes and followed Squeers across a yard to the school-room. "There," said the schoolmaster, as they stepped in together, "this is our shop." It was a bare and dirty room, the windows mostly stopped up with old copybooks and paper, and Nicholas looked with dismay at the old rickety desks and forms. But the pupils! Pale and haggard faces, lank and bony figures, boys of stunted growth, and others whose long and meagre legs would hardly bear their stooping bodies. Faces that told of young lives which from infancy had been one horrible endurance of cruelty and neglect. Little faces that should have been handsome, darkened with the scowl of sullen, dogged suffering. And yet, painful as the scene was, it had its grotesque features. Mrs. Squeers, wearing a beaver bonnet of some antiquity on the top of a nightcap, stood at the desk, presiding over an immense basin of brimstone and treacle. This compound she administered to each boy in succession, using an enormous wooden spoon for the purpose. "We purify the boys' blood now and then, Nickleby," said Squeers, when the operation was over. A meagre breakfast followed; and then Mr. Squeers made his way to his desk, and called up the first class. "This is the first class in English spelling and philosophy, Nickleby," said Squeers, beckoning Nicholas to stand beside him. "Now then, where's the first boy?" "Please, sir, he's cleaning the back parlour window." "So he is, to be sure," replied Squeers. "We go upon the practical mode of teaching, Nickleby; the regular education system. C-l-e-a-n, clean, verb active, to make bright. W-i-n, win; d-e-r, winder, a casement. When the boy knows this out of a book, he goes and does it. Where's the second boy?" "Please, sir, he's weeding the garden." "So he is," said Squeers. B-o-t, bot; t-i-n, bottin; n-e-y, ney, bottiney, noun substantive, a knowledge of plants. When he has learned that bottiney means a knowledge of plants, he goes and knows 'em. That's our system, Nickleby. Third boy, what's a horse?" "A beast, sir," replied the boy. "So it is," said Squeers. "A horse is a quadruped, and quadruped's Latin for beast, as everybody that's gone through the grammar knows. As you're perfect in that, go and look after my horse, and rub him down well, or I'll rub you down. The rest of the class go and draw water up, till somebody tells you to leave off, for it's washing day to-morrow, and they want the coppers filled." The deficiencies of Mr. Squeers' scholastic methods were made up by lavish punishments, and Nicholas was compelled to stand by every day and see the unfortunate pupils of Dotheboys Hall beaten without mercy, and know that he could do nothing to alleviate their misery. In particular the plight of one poor boy, older than the rest, called Smike, a drudge whom starvation and ill-treatment had rendered dull and slow-witted, aroused all Nicholas's pity. It was Smike who was the cause of Nicholas leaving Yorkshire. Nicholas could endure the coarse and brutal language of Squeers, the displeasure of Mrs. Squeers (who decided that the new usher was "a proud, haughty, consequential, turned-up-nosed peacock," and that "she'd bring his pride down"), and the petty indignities this lady could inflict upon him. He bore with the bad food, dirty lodging, and daily round of squalid misery in the school. But there came a day when Smike, unable to face his tormentors any longer, ran away. He was taken within four-and-twenty hours, and brought back, bedabbled with mud and rain, haggard and worn - to all appearance more dead than alive. The work this unhappy drudge performed would have cost the establishment some ten or twelve shillings a week in the way of wages, and Squeers, who, as a matter of policy, made severe examples of all runaways from Dotheboys Hall, prepared to take full vengeance on Smike. At the first blow Smike uttered a shriek of pain, and Nicholas Nickleby started up from his desk, and cried "Stop!" in a furious voice. "Touch that boy at your peril. I will not stand by and see it done." He had scarcely spoken, when Squeers, in a violent outbreak of wrath, spat upon him, and struck him across the face with his cane. All Nicholas's feelings of rage, scorn, and indignation were concentrated into that moment, and, smarting at the blow, he sprang upon the schoolmaster, wrested the weapon from him, and, pinning him by the throat, beat the ruffian until he roared for mercy. Mrs. Squeers, with many shrieks for aid, hung on to the tail of her partner's coat, and tried to drag him from his infuriated adversary. With the result that when Nicholas, having thrown all his remaining strength into a half dozen finishing cuts, flung the schoolmaster from him with all the force he could muster, Mrs. Squeers was precipitated over an adjacent form; and Squeers, striking his head against it in his descent, lay at full length on the ground, stunned and motionless. Nicholas, assured that Squeers was only stunned, and not dead, left the room, packed up his few clothes in a small leathern valise, marched boldly out by the front door, and struck into the road for London. III. - Brighter Days for Nicholas After many adventures in the quest of fortune, Nicholas, who had spurned all further connection with his uncle, stood one day outside a registry office in London. And as he stood there looking at the various placards in the window, an old gentleman, a sturdy old fellow in broad-skirted blue coat, happened to stop too. Nicholas caught the old gentleman's eye, and began to wonder whether the stranger could by any possibility be looking for a clerk or secretary. As the old gentleman moved away he noticed that Nicholas was about to speak, and good-naturedly stood still. "I was only going to say," said Nicholas, "that I hoped you had some object in consulting those advertisements in the window." "Ay, ay; what object now?" returned the old gentleman. "Did you think I wanted a situation now, eh? I thought the same of you, at first, upon my word I did." "If you had thought so at last, too, sir, you would not have been far from the truth," rejoined Nicholas. "The kindness of your face and manner - both so unlike any I have ever seen - tempt me to speak in a way I should never dream of doing to a stranger in this wilderness of London." "Wilderness! Yes, it is; it is. It was a wilderness to me once. I came here barefoot - I have never forgotten it. What's the matter, how did it all come about?" said the old man, laying his hand on the shoulder of Nicholas, and walking him up the street. "In mourning, too, eh?" laying his finger on the sleeve of his black coat. "My father," replied Nicholas. "Bad thing for a young man to lose his father. Widowed mother, perhaps?" Nicholas nodded. "Brothers and sisters, too, eh?" "One sister." "Poor thing, poor thing! You're a scholar too, I dare say. Education's a great thing. I never had any. I admire it the more in others. A very fine thing. Tell me more of your history, all of it. No impertinent curiosity - no, no!" There was something so earnest and guileless in the way this was said that Nicholas could not resist it. So he told his story, and, at the end, the old gentleman carried him straight off to the City, where they emerged in a quiet, shady square. The old gentleman led the way into some business premises, which had the inscription, "Cheeryble Brothers," on the doorpost, and stopped to speak to an elderly, large-faced clerk in the counting-house. "Is my brother in his room, Tim?" said Mr. Cheeryble. "Yes, he is, sir," said the clerk. What was the amazement of Nicholas when his conductor took him into a room and presented him to another old gentleman, the very type and model of himself - the same face and figure, the same clothes. Nobody could have doubted their being twin brothers. "Brother Ned," said Nicholas's friend, "here is a young friend of mine that we must assist." Then brother Charles related what Nicholas had told him. And, after that, and some conversation between the brothers, Tim Linkinwater was called in, and brother Ned whispered a few words in his ear. "Tim," said brother Charles, "you understand that we have an intention of taking this young gentleman into the counting-house." Brother Ned remarked that Tim quite approved of it, and Tim, having nodded, said, with resolution, "But I'm not coming an hour later in the morning, you know. I'm not going to the country either. It's forty-four years since I first kept the books of Cheeryble Brothers. I've opened the safe all that time every morning at nine, and I've never slept out of the back attic one single night. This ain't the first time you've talked about superannuating me, Mr. Edwin and Mr. Charles; but, if you please, we'll make it the last, and drop the subject for evermore." With which words Tim Linkinwater stalked out, with the air of a man who was thoroughly resolved not to be put down. The brothers coughed. "He must be done something with, brother Ned. We must, disregard his scruples; he must be made a partner." "Quite right, quite right, brother Charles. If he won't listen to reason, we must do it against his will. But, in the meantime, we are keeping our young friend, and the poor lady and her daughter will be anxious for his return. So let us say good-bye for the present." And at that the brothers hurried Nicholas out of the office, shaking hands with him all the way. That was the beginning of brighter days for Nicholas and for Mrs. Nickleby and Kate. The brothers Cheeryble not only took Nicholas into their office, but a small cottage at Bow, then quite out in the country, was found for the widow and her children. There never was such a week of discoveries and surprises as the first week at that cottage. Every night when Nicholas came home, something new had been found. One day it was a grape-vine, and another day it was a boiler, and another day it was the key of the front parlour cupboard at the bottom of the water-butt, and so on through a hundred items. As for Nicholas's work in the counting-house, Tim Linkinwater was satisfied with the young man the very first day. Tim turned pale and stood watching with breathless anxiety when Nicholas made his first entry in the books of Cheeryble Brothers, while the two brothers looked on with smiling faces. Presently the old clerk nodded his head, signifying "He'll do." But when Nicholas stopped to refer to some other page, Tim Linkinwater, unable to restrain his satisfaction any longer, descended from his stool, and caught him rapturously by the hand. "He has done it!" said Tim, looking round triumphantly at his employers. "His capital 'B's' and 'D's' are exactly like mine; he dots his small 'i's' and crosses every 't.' There ain't such a young man in all London. The City can't produce his equal. I challenge the City to do it!" IV. - The Brothers Cheeryble In course of time the brothers Cheeryble, in their frequent visits to the cottage at Bow, often took with them their nephew Frank; and it also happened that Miss Madeline Bray, a ward of the brothers, was taken to the cottage to recover from a serious illness. Nicholas, from the first time he had seen Madeline in the office of Cheeryble Brothers, had fallen in love with her; but he decided that as an honourable man no word of love must pass his lips. While Kate Nickleby had been equally firm in declining to listen to any proposal from Frank. It was some time after Madeline had left the cottage, and Nicholas and Kate had begun to try in good earnest to stifle their own regrets, and to live for each other and for their mother, when there came one evening, per Mr. Linkinwater, an invitation from the brothers to dinner on the next day but one. "You may depend on it that this means something besides dinner," said Mrs. Nickleby solemnly. When the great day arrived who should be there at the house of the brothers but Frank and Madeline. "Young men," said brother Charles, "shake hands." "I need no bidding to do that," said Nicholas. "Nor I," rejoined Frank, and the two young men clasped hands heartily. The old gentleman took them aside. "I wish to see you friends - close and firm friends. Frank, look here! Mrs. Nickleby, will you come on the other side? This is a copy of the will of Madeline's grandfather, bequeathing her the sum of £12,000. Now, Frank, you were largely instrumental in recovering this document. The fortune is but a small one, but we love Madeline. Will you become a suitor for her hand?" "No, sir. I interested myself in the recovery of that instrument, believing that her hand was already pledged elsewhere. In this, it seems, I judged hastily." "As you always do, sir!" cried brother Charles. "How dare you think, Frank, that we could have you marry for money? How dare you go and make love to Mr. Nickleby's sister without telling us first, and letting us speak for you. Mr. Nickleby, sir, Frank judged hastily, but he judged, for once, correctly. Madeline's heart is occupied - give me your hand - it is occupied by you and worthily. She chooses you, Mr. Nickleby, as we, her dearest friends, would have her choose. Frank chooses as we would have him choose. He should have your sister's little hand, sir, if she had refused it a score of times - ay, he should, and he shall! What? You are the children of a worthy gentleman. The time was, sir, when my brother Ned and I were two poor, simple-hearted boys, wandering almost barefoot to seek bur fortunes. Oh, Ned, Ned, Ned, what a happy day this is for you and me! If our poor mother had only lived to see us now, Ned, how proud it would have made her dear heart at last!" So Madeline gave her heart and fortune to Nicholas, and on the same day, and at the same time, Kate became Mrs. Frank Cheeryble. Madeline's money was invested in the firm of Cheeryble Brothers, in which Nicholas had become a partner, and before many years elapsed the business was carried on in the names of "Cheeryble and Nickleby." Tim Linkinwater condescended, after much entreating and brow-beating, to accept a share in the house; but he could never be prevailed upon to suffer the publication of his name as partner, and always persisted in the punctual and regular discharge of his clerkly duties. The twin brothers retired. Who needs to be told that they were happy? The first act of Nicholas, when he became a rich and prosperous merchant, was to buy his father's old house. As time crept on, and there came gradually about him a group of lovely children, it was altered and enlarged; but no tree was rooted up, nothing with which there was any association of bygone times was ever removed or changed. Mr. Squeers, having come within the meshes of the law over some nefarious scheme of Ralph Nickleby's, suffered transportation beyond the seas, and with his disappearance Dotheboys Hall was broken up for good. * * * * * |