|

|

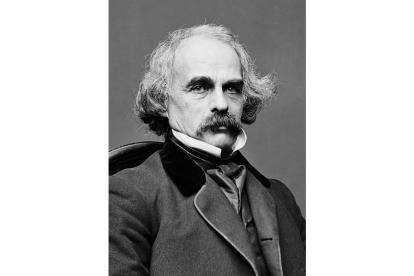

by Nathaniel Hawthorne The original, squashed down to read in about 20 minutes  (1851) Nathaniel Hathorne (July 4, 1804 - May 19, 1864) was a diplomat and story teller from Salem, Massachusetts, a descendant of John Hathorne a judge in the notorious Salem witch trials. Nathaniel altered his name to "Hawthorne" in order to hide this relation. He worked at a Custom House and joined Brook Farm, a transcendentalist community, before a political appointment took Hawthorne and family to Europe. Abridged: JH For more works by Nathaniel Hawthorn, see The Index I. - Consular Experiences The Liverpool Consulate of the United States, in my day, was located in Washington Buildings, in the neighbourhood of some of the oldest docks. Here in a stifled and dusky chamber I spent wearily four good years of my existence. Hither came a great variety of visitors, principally Americans, but including almost every other nationality, especially the distressed and downfallen ones. All sufferers, or pretended ones, in the cause of Liberty sought the American Consulate in hopes of bread, and perhaps to beg a passage to the blessed home of Freedom. My countrymen seemed chiselled in sharper angles than I had imagined at home. They often came to the Consulate in parties merely to see how their public servant was getting on with his duties. No people on earth have such vagabond habits as ourselves. A young American will deliberately spend all his resources in an aesthetic peregrination of Europe. Often their funds held out just long enough to bring them to the doors of my Consulate. Among these stray Americans I remember one ragged, patient old man, who soberly affirmed that he had been wandering about England more than a quarter of a century, doing his utmost to get home, but never rich enough to pay his passage. I recollect another queer, stupid, fat-faced individual, a country shopkeeper from Connecticut, who had come over to England solely to have an interview with the queen. He had named one of his children for her majesty, and the other for Prince Albert, and had transmitted photographs of them to the illustrious godmother, which had been acknowledged by her secretary. He also had a fantastic notion that he was rightful heir to a rich English estate. The cause of this particular insanity lies deep in the Anglo-American heart. We still have an unspeakable yearning towards England, and I might fill many pages with instances of this diseased American appetite for English soil. A respectable-looking woman, exceedingly homely, but decidedly New Englandish, came to my office with a great bundle of documents, containing evidences of her indubitable claim to the site on which all the principal business part of Liverpool has long been situated. All these matters, however, were quite distinct from the real business of that great Consulate, which is now woefully fallen off. The technical details I left to the treatment of two faithful, competent English subordinates. An American has never time to make himself thoroughly qualified for a foreign post before the revolution of the political wheel discards him from his office. For myself, I was not at all the kind of man to grow into an ideal consul. I never desired to be burdened with public influence, and the official business was irksome. When my successor arrived, I drew a long, delightful breath. These English sketches comprise a few of the things that I took note of, in many escapes from my consular servitude. Liverpool is a most convenient point to get away from. I hope that I do not compromise my American patriotism by acknowledging that in visiting many famous localities, I was often conscious of a fervent hereditary attachment to the native soil of our forefathers, and felt it to be our Old Home. II. - A Sentimental Experience There is a small nest of a place in Leamington which I remember as one of the cosiest nooks in England. The ordinary stream of life does not run through this quiet little pool, and few of the inhabitants seem to be troubled with any outside activities. Its original nucleus lies in the fiction of a chalybeate well. I know not if its waters are ever tasted nowadays, but it continues to be a resort of transient visitors. It lies in pleasant Warwickshire at the very midmost point of England, surrounded by country seats and castles, and is the more permanent abode of genteel, unoccupied, not very wealthy people. My chief enjoyment there lay in rural walks to places of interest in the neighbourhood. The high-roads are pleasant, but a fresher interest is to be found in the footpaths which go wandering from stile to stile, along hedges and across broad fields, and through wooded parks. These by-paths admit the wayfarer into the very heart of rural life. Their antiquity probably exceeds that of the Roman ways; the footsteps of the aboriginal Britons first wore away the grass, and the natural flow of intercourse from village to village has kept the track bare ever since. An American farmer would plough across any such path. Old associations are sure to be fragrant herbs in English nostrils, but we pull them up as weeds. I remember such a path, which connects Leamington with the small village of Lillington. The village consists chiefly of one row of dwellings, growing together like the cells of a honeycomb, without intervening gardens, grass-plots, orchards, or shade trees. Beyond the first row there was another block of small, old cottages with thatched roofs. I never saw a prettier rural scene. In front of the whole row was a luxuriant hawthorne hedge, and belonging to each cottage was a little square of garden ground. The gardens were chock-full of familiar, bright-coloured flowers. The cottagers evidently loved their little nests, and kindly nature helped their humble efforts with its flowers, moss, and lichens. Not far from these cottages a green lane turned aside to an ideal country church and churchyard. The tower was low, massive, and crowned with battlements. We looked into the windows and beheld the dim and quiet interior, a narrow space, but venerable with the consecration of many centuries. A well-trodden path led across the churchyard. Time gnaws an English gravestone with wonderful appetite. And yet this, same ungenial climate has a lovely way of dealing with certain horizontal monuments. The unseen seeds of mosses find their way into the lettered furrows, and are made to germinate by the watery sunshine of the English sky; and by-and-bye, behold, the complete inscription beautifully embossed in velvet moss on the marble slab! I found an almost illegible stone very close to the church, and made out this forlorn verse. Poorly lived, And poorly died; Poorly buried, And no one cried. From Leamington, the road to Warwick is straight and level till it brings you to an arched bridge over the Avon. Casting our eyes along the quiet stream through a vista of willows, we behold the grey magnificence of Warwick Castle. From the bridge the road passes in front of the Castle Gate, and enters the principal street of Warwick. Proceeding westward through the town, we find ourselves confronted by a huge mass of rock, penetrated by a vaulted passage, which may well have been one of King Cymbeline's gateways; and on the top of the rock sits a small, old church, communicating with an ancient edifice that looks down on the street. It presents a venerable specimen of the timber-and-plaster style of building; the front rises into many gables, the windows mostly open on hinges; the whole affair looks very old, but the state of repair is perfect. On a bench, enjoying the sunshine, and looking into the street, a few old men are generally to be seen, wrapped in old-fashioned cloaks and wearing the identical silver badges which the Earl of Leicester gave to the twelve original Brethren of Leicester's Hospital - a community which exists to-day under the modes established for it in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. This sudden cropping-up of an apparently dead and buried state of society produces a picturesque effect. The charm of an English scene consists in the rich verdure of the fields, in the stately wayside trees, and in the old and high cultivation that has humanised the very sods. To an American there is a kind of sanctity even in an English turnip-field. After my first visit to Leamington, I went to Lichfield to see its beautiful cathedral, and because it was the birthplace of Dr. Johnson, with whose sturdy English character I became acquainted through the good offices of Mr. Boswell. As a man, a talker, and a humorist, I knew and loved him. I might, indeed, have had a wiser friend; the atmosphere in which he breathed was dense, and he meddled only with the surface of life. But then, how English! I know not what rank the cathedral of Lichfield holds among its sister edifices. To my uninstructed vision it seemed the object best worth gazing at in the whole world. Seeking for Johnson's birthplace, I found a tall and thin house, with a roof rising steep and high. In a corner-room of the basement, where old Michael Johnson may have sold books, is now what we should call a dry-goods store. I could get no admittance, and had to console myself with a sight of the marble figure sitting in the middle of the Square with his face turned towards the house. A bas-relief on the pedestal shows Johnson doing penance in the market-place of Uttoxeter for an act of disobedience to his father, committed fifty years before. The next day I went to Uttoxeter on a sentimental pilgrimage to see the very spot where Johnson had stood. How strange it is that tradition should not have kept in mind the place! How shameful that there should be no local memorial of this incident, as beautiful and touching a passage as can be cited out of any human life! III. - The English Vanity Fair One summer we found a particularly delightful abode in one of the oases that have grown up on the wide waste of Blackheath. A friend had given us pilgrims and dusty wayfarers his suburban residence, with all its conveniences, elegances, and snuggeries, its lawn and its cosy garden-nooks. I already knew London well, and I found the quiet of my temporary haven more attractive than anything that the great town could offer. Our domain was shut in by a brick wall, softened by shrubbery, and beyond our immediate precincts there was an abundance of foliage. The effect was wonderfully sylvan and rural; only we could hear the discordant screech of a railway-train as it reached Blackheath. It gave a deeper delight to my luxurious idleness that we could contrast it with the turmoil which I escaped. Beyond our own gate I often went astray on the great, bare, dreary common, with a strange and unexpected sense of desert freedom. Once, about sunset, I had a view of immense London, four or five miles off, with the vast dome in the midst, and the towers of the Houses of Parliament rising up into the smoky canopy - a glorious and sombre picture, but irresistibly attractive. The frequent trains and steamers to Greenwich have made Blackheath a playground and breathing-place for Londoners. Passing among these holiday people, we come to one of the gateways of Greenwich Park; it admits us from the bare heath into a scene of antique cultivation, traversed by avenues of trees. On the loftiest of the gentle hills which diversify the surface of the park is Greenwich Observatory. I used to regulate my watch by the broad dial-plate against the Observatory wall, and felt it pleasant to be standing at the very centre of time and space. The English character is by no means a lofty one, and yet an observer has a sense of natural kindness towards them in the lump. They adhere closer to original simplicity; they love, quarrel, laugh, cry, and turn their actual selves inside out with greater freedom than Americans would consider decorous. It was often so with these holiday folk in Greenwich Park, and I fancy myself to have caught very satisfactory glimpses of Arcadian life among the cockneys there. After traversing the park, we come into the neighbourhood of Greenwich Hospital, an establishment which does more honour to the heart of England than anything else that I am acquainted with. The hospital stands close to the town, where, on Easter Monday, it was my good fortune to behold the festivity known as Greenwich Fair. I remember little more of it than a confusion of unwashed and shabbily dressed people, such as we never see in our own country. On our side of the water every man and woman has a holiday suit. There are few sadder spectacles than a ragged coat or a soiled gown at a festival. The unfragrant crowd was exceedingly dense. There were oyster-stands, stalls of oranges, and booths with gilt gingerbread and toys for the children. The mob were quiet, civil, and remarkably good-humoured, making allowance for the national gruffness; there was no riot. What immensely perplexed me was a sharp, angry sort of rattle sounding in all quarters, until I discovered that the noise was produced by a little instrument called "the fun of the fair," which was drawn smartly against people's backs. The ladies draw their rattles against the young men's backs, and the young men return the compliment. There were theatrical booths, fighting men and jugglers, and in the midst of the confusion little boys very solicitous to brush your boots. The scene reminded me of Bunyan's description of Vanity Fair. These Englishmen are certainly a franker and simpler people than ourselves, from peer to peasant; but it may be that they owe those manly qualities to a coarser grain in their nature, and that, with a fine one in ours, we shall ultimately acquire a marble polish of which they are unsusceptible. From Greenwich the steamers offer much the most agreeable mode of getting to London. At least, it might be agreeable except for the soot from the stove-pipe, the heavy heat of the unsheltered deck, the spiteful little showers of rain, the inexhaustible throng of passengers, and the possibility of getting your pocket picked. A notable group of objects on the bank of the river is an assemblage of walls, battlements, and turrets, out of the midst of which rises one great, greyish, square tower, known in English history as the Tower. Under the base of the rampart we may catch a glimpse of an arched water-entrance; it is the Traitor's Gate, through which a multitude of noble and illustrious personages have entered the Tower on their way to Heaven. Later, we have a glimpse of the holy Abbey; while that grey, ancestral pile on the opposite side of the river is Lambeth Palace. We have passed beneath half a dozen bridges in our course, and now we look back upon the mass of innumerable roofs, out of which rise steeples, towers, columns, and the great crowning Dome - look back upon that mystery of the world's proudest city, amid which a man so longs and loves to be, not, perhaps, because it contains much that is positively admirable and enjoyable, but because the world has nothing better. |