|

|

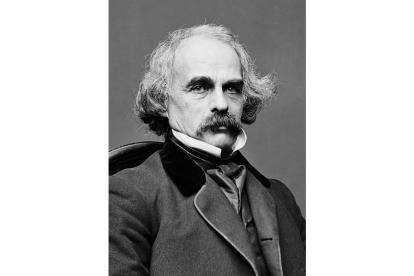

by Nathaniel Hawthorne The original, squashed down to read in about 20 minutes  (1850) Nathaniel Hathorne (July 4, 1804 - May 19, 1864) was a diplomat and story teller from Salem, Massachusetts, a descendant of John Hathorne a judge in the notorious Salem witch trials. Nathaniel altered his name to "Hawthorne" in order to hide this relation. He worked at a Custom House and joined Brook Farm, a transcendentalist community, before a political appointment took Hawthorne and family to Europe. Abridged: JH For more works by Nathaniel Hawthorn, see The Index The grass-plot before the jail in Prison Lane, on a certain summer morning, not less than two centuries ago, was occupied by a pretty large number of the inhabitants of Boston, all with their eyes intently fastened on the iron-clamped oaken door. The door of the jail being flung open from within, there appeared, in the first place, the grim presence of the town-beadle, and following him a young woman who bore in her arms a baby of some three months old. The young woman was tall, and those who had known Hester Prynne before were astonished to perceive how her beauty shone out. On the breast of her gown, in fine red cloth, surrounded with an elaborate embroidery and fantastic flourishes of gold thread, appeared the letter A, and it was that scarlet letter which drew all eyes, and, as it were, transfigured the wearer. A lane was forthwith opened through the crowd of spectators. Preceded by the beadle, and attended by an irregular procession of stern-browed men and unkindly visaged women, Hester Prynne set forth towards the place appointed for her punishment. It was no great distance from the prison door to the market-place, and in spite of the agony of her heart, Hester passed with almost a serene deportment to the scaffold where the pillory was set up. The crowd was sombre and grave, and the unhappy prisoner sustained herself as best a woman might, under the heavy weight of a thousand unrelenting eyes. One man, small in stature, and of a remarkable intelligence in his features, who stood on the outskirts of the crowd, attracted the notice of Hester Prynne, and he in his turn bent his eyes on the prisoner till, seeing she appeared to recognise him, he slowly raised his finger and laid it on his lips. Then, touching the shoulder of a townsman who stood next to him, he said, "I pray you, good sir, who is this woman, and wherefore is she here set up to public shame?" "You must needs be a stranger, friend," said the townsman, "else you would surely have heard of Mistress Hester Prynne, and her evil doings. She hath raised a great scandal in godly Master Dimmesdale's church. The penalty thereof is death. But the magistracy, in their great mercy and tenderness of heart, have doomed Mistress Prynne to stand only a space of three hours on the platform of the pillory, and for the remainder of her natural life to wear a mark of shame upon her bosom." "A wise sentence!" remarked the stranger gravely. "It irks me, nevertheless, that the partner of her iniquity should not at least stand on the scaffold by her side. But he will be known - he will be known!" Directly over the platform on which Hester Prynne stood was a kind of balcony, and here sat Governor Bellingham, with four sergeants about his chair, and ministers of religion. Mr. John Wilson, the eldest of these clergymen, first spake, and then urged a younger minister, Mr. Dimmesdale, to exhort the prisoner to repentance and to confession. "Speak to the woman, my brother," said Mr. Wilson. The Rev. Mr. Dimmesdale was a man of high native gifts, whose eloquence and religious fervour had already wide eminence in his profession. He bent his head, in silent prayer, as it seemed, and then came forward. "Hester Prynne," said he, "if thou feelest it to be for thy soul's peace, I charge thee to speak out the name of thy fellow-sinner and fellow-sufferer. Be not silent from any mistaken pity and tenderness for him, for, believe me, though he were to step down from a high place, and stand there beside thee, on thy pedestal of shame, yet better were it so than to hide a guilty heart through life." Hester only shook her head. "She will not speak," murmured Mr. Dimmesdale. "Wondrous strength and generosity of a woman's heart!" Hester Prynne kept her place upon the pedestal of shame with an air of weary indifference. With the same hard demeanour she was led back to prison. That night the child at her boson writhed in convulsions of pain, and the jailer brought in a physician, whom he announced as Mr. Roger Chillingworth, and who was none other than the stranger whom Hester had noticed in the crowd. He took the infant in his arms and administered a draught, and its moans and convulsive tossings gradually ceased. "Hester," said he, when the jailer had withdrawn, "I ask not wherefore thou hast fallen into the pit. It was my folly and thy weakness. What had I - a man of thought, the bookworm of great libraries - to do with youth and beauty like thine own? I might have known that in my long absence this would happen." "I have greatly wronged thee," murmured Hester. "We have wronged each other," he answered. "But I shall seek this man whose name thou wilt not reveal, as I seek truth in books, and sooner or later he must needs be mine. I shall contrive naught against his life. Let him live! Not the less shall he be mine. One thing, thou that wast my wife, I ask. Thou hast kept his name secret. Keep, likewise, mine. Let thy husband be to the world as one already dead, and breathe not the secret, above all, to the man thou wottest of?" "I will keep thy secret, as I have his." When her prison-door was thrown open, and she came forth into the sunshine, Hester Prynne did not flee. On the outskirts of the town was a small thatched cottage, and there, in this lonesome dwelling, Hester established herself with her infant child. Without a friend on earth who dared to show himself, she, however, incurred no risk of want. She possessed an art that sufficed to supply food for her thriving infant and herself - the art of needlework. By degrees her handiwork became what would now be termed the fashion. She bore on her breast, in the curiously embroidered letter, a specimen of her skill, and her needlework was seen on the ruff of the governor; military men wore it on their scarfs, and the minister on his bands. As time went on, the public attitude to Hester changed. Human nature, to its credit, loves more readily than it hates. Hester never battled with the public, but submitted uncomplainingly to its worst usage, and so a species of general regard had ultimately grown up in reference to her. Hester had named the infant "Pearl," as being of great price, and little Pearl grew up a wondrously lovely child, with a strange, lawless character. At times she seemed rather an airy sprite than human, and never did she seek to make acquaintance with other children, but was always Hester's companion in her walks about the town. At one time some of the leading inhabitants of the place sought to deprive Hester of her child; and at the governor's mansion, whither Hester had repaired, with some gloves which she had embroidered at his order, the matter was discussed in the mother's presence by the governor and his guests - Mr. John Wilson, Mr. Arthur Dimmesdale, and old Roger Chillingworth, now established as a physician of great skill in the town. "God gave me the child!" cried Hester. "He gave her in requital of all things else which ye have taken from me. Ye shall not take her! I will die first! Speak thou for me," she cried turning to the young clergyman, Mr. Dimmesdale. "Thou wast my pastor. Thou knowest what is in my heart, and what are a mother's rights, and how much the stronger they are when that mother has but her child and the scarlet letter! I will not lose the child! Look to it!" "There is truth in what she says," began the minister. "God gave her the child, and there is a quality of awful sacredness between this mother and this child. It is good for this poor, sinful woman that she hath an infant confided to her care - to be trained up by her to righteousness, to remind her and to teach her that, if she bring the child to heaven, the child also will bring its parent thither. Let us then leave them as Providence hath seen fit to place them!" "You speak, my friend, with a strange earnestness," said old Roger Chillingworth, smiling at him. "He hath adduced such arguments that we will even leave the matter as it now stands," said the governor. "So long, at least, as there shall be no further scandal in the woman." The affair being so satisfactorily concluded, Hester Prynne, with Pearl, departed. It was at the solemn request of the deacons and elders of the church in Boston that the Rev. Mr. Dimmesdale went to Roger Chillingworth for professional advice. The young minister's health was failing, his cheek was paler and thinner, and his voice more tremulous with every successive Sabbath. Roger Chillingworth scrutinised his patient carefully, and, accepted as the medical adviser, determined to know the man before attempting to do him good. He strove to go deep into his patient's bosom, delving among his principles, and prying into his recollections. After a time, at a hint from old Roger Chillingworth, the friends of Mr. Dimmesdale effected an arrangement by which the two men were lodged in the same house; so that every ebb and flow of the minister's life-tide might pass under the watchful eye of his anxious physician. Old Roger Chillingworth, throughout life, had been calm in temperament, of kindly affections, and ever in the world a pure and upright man. He had begun an investigation, as he imagined, with the severe integrity of a judge, desirous only of truth. But, as he proceeded, a terrible fascination seized the old man within its grip, and never set him free again until he had done all its bidding. He now dug into the poor clergyman's heart, like a miner searching for gold. "This man," the physician would say to himself at times, "pure as they deem him, hath inherited a strong animal nature from his father or his mother. Let us dig a little farther in the direction of this vein." Henceforth Roger Chillingworth became not a spectator only, but a chief actor in the poor minister's inner world. And Mr. Dimmesdale grew to look with unaccountable horror and hatred at the old physician. And still the minister's fame and reputation for holiness increased, even while he was tortured by bodily disease and the black trouble of his soul. More than once Mr. Dimmesdale had gone into the pulpit, with a purpose never to come down until he should have spoken the truth of his life. And ever he put a cheat upon himself by confessing in general terms his exceeding vileness and sinfulness. One night in early May, driven by remorse, and still indulging in the mockery of repentance, the minister sought the scaffold, where Hester Prynne had stood. The town was all asleep. There was no peril of discovery. And yet his vigil was surprised by Hester and her daughter, returning from a death-bed in the town, and presently by Roger Chillingworth himself. "Who is that man?" gasped Mr. Dimmesdale, in terror. "I shiver at him, Hester. Canst thou do nothing for me? I have a nameless horror of the man!" Hester remembered her promise and was silent. "Worthy sir," said the physician, when he had advanced to the foot of the platform, "pious Master Dimmesdale! Can this be you? Come, good sir, I pray you, let me lead you home! You should study less, or these night-whimseys will grow upon you." "I will go home with you," said Mr. Dimmesdale. And now Hester Prynne resolved to do what might be in her power for the victim whom she saw in her former husband's grip. An opportunity soon occurred when she met the old physician stooping in quest of roots to concoct his medicines. "When we last spake together," said Hester, "you bound me to secrecy touching our former relations. But now I must reveal the secret. He must discern thee in thy true character. What may be the result I know not. So far as concerns the overthrow or preservation of his fair fame and his earthly state, and perchance his life, he is in thy hands. Nor do I - whom the scarlet letter has disciplined to truth - nor do I perceive such advantage in his living any longer a life of ghastly emptiness, that I shall stoop to implore thy mercy. Do with him as thou wilt! There is no good for him, no good for me, no good for thee! There is no good for little Pearl!" "Woman, I could well-nigh pity thee!" said Roger Chillingworth. "Peradventure, hadst thou met earlier with a better love than mine, this evil had not been. I pity thee, for the good that has been wasted in thy nature!" "And I thee," answered Hester Prynne, "for the hatred that has transformed a wise and just man to a fiend! Forgive, if not for his sake, then doubly for thine own!" "Peace, Hester, peace!" replied the old man with gloom. "It is not granted me to pardon. It is our fate. Now go thy ways, and deal as thou wilt with yonder man." A week later Hester Prynne waited in the forest for the minister as he returned from a visit to his Indian converts. He walked slowly, and, as he walked, kept his hand over his heart. "Arthur Dimmesdale! Arthur Dimmesdale!" she cried out. "Who speaks?" answered the minister. "Hester! Hester Prynne! Is it thou?" He fixed his eyes upon her and added, "Hester, hast thou found peace?" "Hast thou?" she asked. "None! Nothing but despair! What else could I look for, being what I am, and leading such a life as mine?" "You wrong yourself in this," said Hester gently. "Your sin is left behind you, in the days long past. But Arthur, an enemy dwellest with thee, under the same roof. That old man - the physician, whom they call Roger Chillingworth - he was my husband! Forgive me. Let God punish!" "I do forgive you, Hester," replied the minister. "May God forgive us both!" They sat down, hand clasped in hand, on the mossy trunk of a fallen tree. It was Hester who bade him hope, and spoke of seeking a new life beyond the seas, in some rural village in Europe. "Oh, Hester," cried Arthur Dimmesdale, "I lack the strength and courage to venture out into the wide, strange world alone." "Thou shalt not go alone!" she whispered. Before Mr. Dimmesdale reached home he was conscious of a change of thought and feeling; Roger Chillingworth observed the change, and knew that now in the minister's regard he was no longer a trusted friend, but his bitterest enemy. A New England holiday was at hand, the public celebration of the election of a new governor, and the Rev. Arthur Dimmesdale was to preach the election sermon. Hester had taken berths in a vessel that was about to sail; and then, on the very day of holiday, the shipmaster told her that Roger Chillingworth had also taken a berth in the same vessel. Hester said nothing, but turned away, and waited in the crowded market-place beside the pillory with Pearl, while the procession re-formed after public worship. The street and the market-place absolutely bubbled with applause of the minister, whose sermon had surpassed all previous utterances. At that moment Arthur Dimmesdale stood on the proudest eminence to which a New England clergyman could be exalted. The minister, surrounded by the leading men of the town, halted at the scaffold, and, turning towards it, cried, "Hester, come hither! Come, my little Pearl!" Leaning on Hester's shoulder, the minister, with the child's hand in his, slowly ascended the scaffold steps. "Is not this better," he murmured, "than what we dreamed of in the forest? For, Hester, I am a dying man. So let me make haste to take my shame upon me." "I know not. I know not." "Better? Yea; so we may both die, and little Pearl die with us." He turned to the market-place and spoke with a voice that all could hear. "People of New England! At last, at last I stand where seven years since I should have stood. Lo, the scarlet letter which Hester wears! Ye have all shuddered at it! But there stood one in the midst of you, at whose hand of sin and infamy ye have not shuddered! Stand any here that question God's judgement on a sinner? Behold a dreadful witness of it!" With a convulsive motion he tore away the ministerial gown from before his breast. It was revealed! For an instant the multitude gazed with horror on the ghastly miracle, while the minister stood with a flush of triumph in his face. Then, down he sank upon the scaffold. Hester partly raised him, and supported his head against her bosom. Old Roger Chillingworth knelt beside him. "Thou hast escaped me!" he repeated more than once. "May God forgive thee!" said the minister. "Thou, too, hast deeply sinned!" He fixed his dying eyes on the woman and the child. "My little Pearl," he said feebly, "thou wilt kiss me. Hester, farewell. God knows, and He is merciful! His will be done! Farewell." That final word came forth with the minister's expiring breath. The multitude, silent till then, broke out in a strange, deep voice of awe and wonder. After many days there was more than one account of what had been witnessed on the scaffold. Most of the spectators testified to having seen, on the breast of the unhappy minister, a scarlet letter imprinted in the flesh. Others denied that there was any mark whatever on his breast, more than on a new-born infant's. According to these highly respectable witnesses the minister's confession implied no part of the guilt of Hester Prynne, but was to teach us that we were all sinners alike. Old Roger Chillingworth died and bequeathed his property to little Pearl. For years the mother and child lived in England, and then Pearl married, and Hester returned alone to the little cottage by the forest. |