|

|

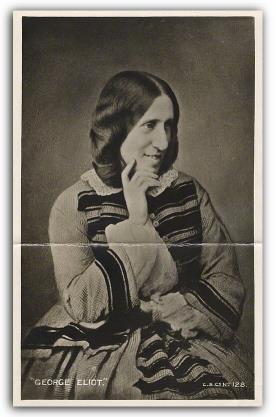

by 'George Eliot' (Mary Ann Evans) The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (1860) Mary Ann Evans ("George Eliot") was born Nov. 22, 1819, at South Farm, Arbury, Warwickshire, England, where her father was agent on the Newdigate estate. Mary established herself as one of the leading novelists of the Victorian era using the male pen name 'George Eliot' she said to ensure her works were taken seriously, but possibly also to shield her identity and hide her close relationship with the married George Henry Lewes. Abridged: JH/GH For more works by George Eliot, see The Index "What I want, you know," said Mr. Tulliver, "what I want is to give Tom a good eddication - an eddication as'll be a bread to him. I mean to put him to a downright good school at midsummer. The two years at th' academy 'ud ha' done well enough if I'd meant to make a miller and farmer of him, but I should like Tom to be a bit of a scholard. It 'ud be a help to me wi' these lawsuits, and arbitrations, and things. I wouldn't make a downright lawyer o' the lad - I should be sorry for him to be a raskill - but a sort of engineer, or a surveyor, or an auctioneer and vallyer, like Riley, or one o' them smartish businesses as are all profits and no outlay, only for a big watch-chain and a high stool. They're pretty nigh all one, and they're not far off being even wi' the law, I believe; for Riley looks Lawyer Wakem i' the face as hard as one cat looks another. He's none frightened at him." Mr. Tulliver was speaking to his wife, a blonde, comely woman, nearly forty years old. "Well, Mr. Tulliver, you know best. I've no objections. But if Tom's to go to a new school, I should like him to go where I can wash him and mend him, else he might as well have calico as linen. And then, when the box is goin' backwards and forwards, I could send the lad a cake, or a pork-pie, or an apple." "Well, well, we won't send him out o' reach o' the carrier's cart, if other things fit in," said Mr. Tulliver. "Riley's as likely a man as any to know o' some school; he's had schooling himself, an' goes about to all sorts o' places - arbitratin' and vallyin', and that." So a day or two later Mr. Riley, the auctioneer, came to Dorlcote Mill, and stayed the night, the better that Mr. Tulliver, who was slow at coming to a point, might consult him on the all-important subject of his boy. "You see, I want to put him to a new school at midsummer," said Mr. Tulliver, when the topic had been reached. "I want to send him to a downright good school, where they'll make a scholard of him. I don't mean Tom to be a miller an' farmer. I see no fun i' that. I shall give Tom an eddication and put him to a business as he may make a nest for himself, an' not want to push me out o' mine." At the sound of her brother's name, Maggie, the second and only other child of the Tullivers, who was seated on a low stool close by the fire, with a large book open on her lap, looked up eagerly. Tom, it appeared, was supposed capable of turning his father out of doors. This was not to be borne, and Maggie jumped up from her stool, and going up between her father's knees, said, in a half-crying, half-indignant voice, "Father, Tom wouldn't be naughty to you ever; I know he wouldn't." Mr. Tulliver's heart was touched. "What! They mustn't say any harm o' Tom, eh?" he said, looking at Maggie with a twinkling eye. Then, in a lower voice, turning to Mr. Riley, "She understands what one's talking about so as never was. And you should hear her read - straight off, as if she knowed it all beforehand. But it's bad - it's bad. A woman's no business wi' being so clever; it'll turn to trouble, I doubt. It's a pity, but what she'd been the lad - she'd ha' been a match for the lawyers, she would." Mr. Riley took a pinch of snuff before he said, "But your lad's not stupid, is he? I saw him, when I was here last, busy making fishing-tackle; he seemed quite up to it." "Well, he isn't not to say stupid; he's got a notion o' things out o' door, an' a sort o' commonsense, as he'd lay hold o' things by the right handle. But he's slow with his tongue, you see, and reads but poorly, and can't abide the books, and spells all wrong, they tell me, an' as shy as can be wi' strangers. Now, what I want is to send him to a school where they'll make him a bit nimble with his tongue and his pen, to make a smart chap of him. I want my son to be even wi' these fellows as have got the start o' me with schooling." The talk ended in Mr. Riley recommending a country parson named Stelling as a suitable tutor for Tom, and Mr. Tulliver decided that his son should go to Mr. Stelling at King's Lorton, fifteen miles from Dorlcote Mill. Tom Tulliver's sufferings during the first quarter he was at King's Lorton, under the distinguished care of the Rev. Walter Stelling, were rather severe. It had been very difficult for him to reconcile himself to the idea that his school-time was to be prolonged, and that he was not to be brought up to his father's business, which he had always thought extremely pleasant, for it was nothing but riding about, giving orders, and going to market. Mr. Stelling was not a harsh-tempered or unkind man - quite the contrary, but he thought Tom a stupid boy, and determined to develop his powers through Latin grammar and Euclid to the best of his ability. As for Tom, he had no distinct idea how there came to be such a thing as Latin on this earth. It would have taken a long while to make it conceivable to him that there ever existed a people who bought and sold sheep and oxen, and transacted the everyday affairs of life through the medium of this language, or why he should be called upon to learn it, when its connection with those affairs had become entirely latent. He was of a very firm, not to say obstinate disposition, but there was no brute-like rebellion or recklessness in his nature; the human sensibilities predominated, and he was anxious to acquire Mr. Stelling's approbation by showing some quickness at his lessons, if he had known how to accomplish it. In his secret heart Tom yearned to have Maggie with him, and, before the first dreary half-year was ended, Maggie actually came. Mrs. Stelling had given a general invitation for the little girl to come and stay with her brother; so when Mr. Tulliver drove over to King's Lorton late in October, Maggie came too, with the sense that she was taking a great journey, and beginning to see the world. "Well, my lad," Mr. Tulliver said, "you look rarely! School agrees with you!" "I don't think I am well, father," said Tom; "I wish you'd ask Mr. Stelling not to let me do Euclid - it brings on the toothache, I think." "Euclid, my lad - why, what's that?" said Mr. Tulliver. "Oh, I don't know! It's definitions and axioms and triangles and things. It's a book I've got to learn in - there's no sense in it." "Go, go!" said Mr. Tulliver reprovingly. "You mustn't say so. You must learn what your master tells you. He knows what it's right for you to learn." In the second term Mr. Stelling had a second pupil - Philip, the son of Lawyer Wakem, Mr. Tulliver's standing enemy. Philip was a very old-looking boy, Tom thought. His spine had been deformed through an accident in infancy, and to Tom he was simply a humpback. He had a vague notion that the deformity of Wakem's son had some relation to the lawyer's rascality, of which he had so often heard his father talk with hot emphasis. There was a natural antipathy of temperament between the two boys; for Tom was an excellent bovine lad, and Philip was sensitive, and suffered acute pain when the other blurted out offensive things. Maggie, on her second visit to King's Lorton, pronounced Philip to be "a nice boy." "He couldn't choose his father, you know," she said to Tom. "And I've read of very bad men who had good sons, as well as good parents who had bad children." "Oh, he's a queer fellow," said Tom curtly, "and he's as sulky as can be with me because I told him his father was a rogue. And I'd a right to tell him so, for it was true - and he began it with calling me names." An accident to Tom's foot brought the two boys nearer again, and also threw Philip and Maggie together. "Maggie," said Philip one day, "if you had had a brother like me, do you think you should have loved him as well as Tom?" "Oh, yes, better," she answered immediately. "No, not better; because I don't think I could love you better than Tom. But I should be so sorry - so sorry for you." Philip coloured. He had meant to imply, would she love him as well in spite of his deformity, and yet when she alluded to it so plainly he winced under her pity. Maggie, young as she was, felt her mistake. "But you are so very clever, Philip, and you can play and sing," she added quickly. "I wish you were my brother. I'm very fond of you." "But you'll go away soon, and go to school, Maggie, and then you'll forget all about me, and not care for me any more." "Oh, no, I shan't forget you, I'm sure." And Maggie put her arm round his neck, and kissed him quite earnestly. When Tom had turned sixteen, and Maggie, three years younger, was at boarding school, came the downfall of the Tullivers. A long and expensive law-suit concerning rights of water, brought by Mr. Tulliver, ended in defeat. Wakem was his opponent's lawyer. Maggie broke the news to Tom. Not only would mill and lands and everything be lost, and nothing left, but their father had fallen off his horse, and knew nobody, and seemed to have lost his senses. "They say Mr. Wakem has got a mortgage or something on the land, Tom," said Maggie, on their way home from King's Lorton. "It was the letter with that news in it that made father ill, they think." "I believe that scoundrel's been planning all along to ruin my father," said Tom, leaping from the vaguest impressions to a definite conclusion. "I'll make him feel for it when I'm a man. Mind you never speak to Philip again!" For more than two months Mr. Tulliver lay ill in his room, oblivious to all that was taking place around him. From time to time recognition came to him of his wife and family, but there was no remembrance of recent events. The mill and land of the Tullivers were sold to Wakem the lawyer, and the bulk of their household goods were disposed of by public auction; but the Tullivers were not turned out of Dorlcote Mill. And, indeed, when Mr. Tulliver, known to be a man of proud honesty, was once more able to be up and about, it was proposed that he should remain and accept employment as manager of the mill for Mr. Wakem. It was with difficulty that poor Tulliver could bring himself to accept the situation, but he saw the possibility, by much pinching, of saving money out of the thirty shillings a week salary promised by Wakem, and paying a second dividend to his creditors. The strongest influence of all was the love of the old premises where he had run about when he was a boy, just as Tom had done after him. Tom, who had at once applied to his Uncle Deane, partner in a wealthy merchant's business, for work, and was now earning a pound a week, had protested against entertaining the proposition; he shouldn't like his father to be under Wakem; he thought it would look nothing but mean spirited. But Mr. Tulliver had come to a decision. The first evening of his new life downstairs, he called his family round him, and began to speak, looking first at his wife. "I've made up my mind, Bessy. I'll stop in the old place, and I'll serve under Wakem, and I'll serve him like an honest man; there's no Tulliver but what's honest, mind that, Tom. They'll have it to throw up against me as I paid a dividend - but it wasn't my fault - it was because there's raskills in the world. They've been too many for me, and I must give in. But I'll serve him as honest as if he was no raskill. I'm an honest man, though I shall never hold my head up no more! I'm a tree as is broke - a tree as is broke." He paused, and looked on the ground. Then suddenly raising his head, he said, in a louder yet deeper tone, "But I won't forgive him! I know what they say - he never meant me any harm! I shouldn't ha' gone to law they say. But who made it so as there was no arbitrating and no justice to be got? It signifies nothing to him - I know that he's one o' them fine gentlemen as get money by doing business for poorer folks, and when he's made beggars of 'em he'll give 'em charity. I won't forgive him! I wish he might be punished with shame till his own son 'ud like to forget him. And you mind this, Tom - you never forgive him, neither, if you mean to be my son. Now write - write it i' the Bible!" "Oh, father, what?" said Maggie. "It's wicked to curse and bear malice." "It isn't wicked, I tell you," said her father, fiercely. "It's wicked as the raskills should prosper - it's the devil's doing. Do as I tell you, Tom! Write." The big Bible was open at the beginning, where many family entries were put down. "What am I to write, father?" said Tom, with gloomy submission. "Write as your father, Edward Tulliver, took service under John Wakem, the man as had helped to ruin him, because I'd promised my wife to make her what amends I could, and because I wanted to die in th' old place where I was born, and my father was born. Put that i' the right words - you know how - and then write as I don't forgive Wakem for all that; and for all I'll serve him honest, I wish evil may befall him. Write that." There was a dead silence as Tom's pen moved along the paper. "Now let me hear what you've wrote," said Mr. Tulliver; and Tom read aloud, slowly. "Now, write - write as you'll remember what Wakem's done to your father, and you'll make him and his feel it, if ever the day comes. And sign your name - Thomas Tulliver!" "Oh, no, father, dear father!" said Maggie, trembling like a leaf. "You shouldn't make Tom write that!" "Be quiet, Maggie!" said Tom, impatiently, "I shall write it!" The Red Deeps was always a favourite place to Maggie to walk in. An old stone quarry, so long exhausted that both mounds and hollows were now clothed with brambles and trees, and with here and there a stretch of grass which a few sheep kept close nibbled. This was the Red Deeps, and it was here in June that Maggie once more met Philip Wakem, five years after their first meeting at Mr. Stelling's. He told her that she was much more beautiful than he had thought she would be, and assured her, in answer to the difficulties she raised as to their meeting, that there was no enmity in his father's mind. And Maggie went home with an inward conflict already begun, and Philip went home to do nothing but remember and hope. In the following April they met again, after Philip had been abroad. And now he took her hand, and asked her the simple question, "Do you love me?" "I think I could hardly love anyone better; there is nothing but what I love you for," Maggie answered. But she pointed out how impossible even their friendship was, if it were discovered. Philip, on his side, refused to give up hope, and before they parted that day she had kissed him. Tom intervened before the next visit to the Red Deeps. He had heard that Philip Wakem had been seen there with his sister, and Maggie admitted, on his questioning her, that she had told Philip that she loved him. "Now, then, Maggie," Tom said coldly, "there are but two courses for you to take. Either you vow solemnly to me, with your hand on father's Bible, that you will never have another meeting or speak another word in private to Philip Wakem, or you refuse and I tell my father everything!" In vain Maggie pleaded. Tom was obdurate, and she repeated the words of renunciation. But that was not enough for Tom Tulliver; he accompanied Maggie to Red Deeps, and in a voice of harsh scorn told Philip that he had been taking a mean, unmanly advantage. "It was for my father's sake, Philip," said Maggie, imploringly. "Tom threatens to tell my father - and he couldn't bear it. I have promised, I have vowed solemnly, that we will not have any intercourse without my brother's knowledge." "It is enough, Maggie. I shall not change, but I wish you to hold yourself entirely free. But trust me - remember that I can never seek for anything but good to what belongs to you." Tom only replied with angry contempt, and led Maggie away. All his sister's remonstrances he answered with cold obstinacy. For his character in its strength was hard. Tom had laboured to one end in these years: to pay off his father's creditors, and regain Dorlcote Mill. By his industry, and by some successful private ventures in trade, the day came when the first of the objects was realised, and Mr. Tulliver lived to see himself free of debt. But Mr. Tulliver's satisfaction was short-lived. Excited by the dinner given to celebrate the payment of his creditors, he met Mr. Wakem near the mill. From angry words it came to blows, and Tulliver fell on the lawyer furiously, only ceasing from attack when Maggie and Mrs. Tulliver appeared. Wakem went off without serious injury, but Tulliver only lived through the night; the excitement had killed him. "You must take care of her, Tom," said the dying man, turning to his daughter. "You'll manage to pay for a brick grave, Tom, so as your mother and me can lie together? This world's...too many...honest man..." At last there was total stillness, and poor Tulliver's dimly lighted soul had ceased to be vexed with the painful riddle of this world. Tom and Maggie went downstairs together, and Maggie spoke. "Tom, forgive me; let us always love each other" - and they clung and wept together. But they were not to be always united. Tom lived in lodgings in the town, and was anxious to provide for his sister, but Maggie preferred to take up teaching in her old boarding-school. She met Philip Wakem again, and though Tom released her from her old promise, he could not regard Philip with any feelings of friendship. It was when Tom had, by years of steady work, fulfilled his father's wishes and become once more master of Dorlcote Mill that Maggie returned - to be no more separated from her brother. She was staying in the town near the river on the night when the flood came, and the river rose beyond its banks. Her first thought, as the water entered the lower part of the house, was of the mill, where Tom was. There was no time to get assistance; she must go herself, and alone. Hastily she procured a boat, and at last reached the mill. The water was up to the first story, but still the mill stood firm. "Tom, where are you? Here is Maggie!" she called out, in a loud, piercing voice. Tom opened the middle window, and got into the boat. Tom rowed with vigour, but a new danger was before them in the river. "Get out of the current!" was shouted at them, but it could not be done at once. Huge fragments of machinery, swept off one of the wharves, blocked the stream in one wide mass, and the current swept the boat swiftly on to its doom. "It is coming, Maggie!" Tom said, in a deep, hoarse voice, loosing the oars and clasping her. The next instant the boat was no longer seen upon the water, and brother and sister had gone down in an embrace never to be parted; living through again in one supreme moment the days when they had clasped their little hands in love. "In their death they were not divided." |